In the South Pacific, which the Japanese attacked in early 1942 with the force of a battering ram, capturing New Britain along with the fortress of Rabaul and then occupying the islands of the Solomon Archipelago, the Americans had no aerial forces. The entire effort to defend this vital part of the ocean had to be borne by the mobile forces of the US Navy and its aircraft carriers, which at the time were not very many. Why was this stretch of ocean so vital? Simply put, because the supply routes connecting Australia with the United States ran right through it. And it was these routes that the Japanese wanted to cut by occupying the Solomon Islands together with the neighbouring archipelagos. It was not until the summer of 1942 that the USAAF began to redeploy fighter squadrons to the area; these were equipped primarily with the Airacobra – mainly P-400s returned by the British.

Range of Japanese expansion, Summer 1942. Map: Public Domain via wikimedia

Airacobras in British Style

The first unit to achieve combat readiness was the 67th Fighter Squadron operating from New Caledonia. There, in July 1942, the airmen collected crates of dismantled Airacobras. The vast majority of these were lend-lease P-400s.

Problems with the “Britishness” of the P-400 arose as soon as the boxes were opened. Inside, there were no standard instructions on how to put the aircraft together. Mechanics had only the manuals attached to the American versions, but these differed somewhat. This greatly delayed their assembly. It took no less than twenty-nine days to piece the thirty airframes together. In addition, the “British” P-400s were not provided with any spares, so that throughout the Guadalcanal campaign they would be repaired using “scraps”, that is, parts taken from damaged and written-off aircraft.

Ground crew at work on Airacobra. South Pacific, 1942

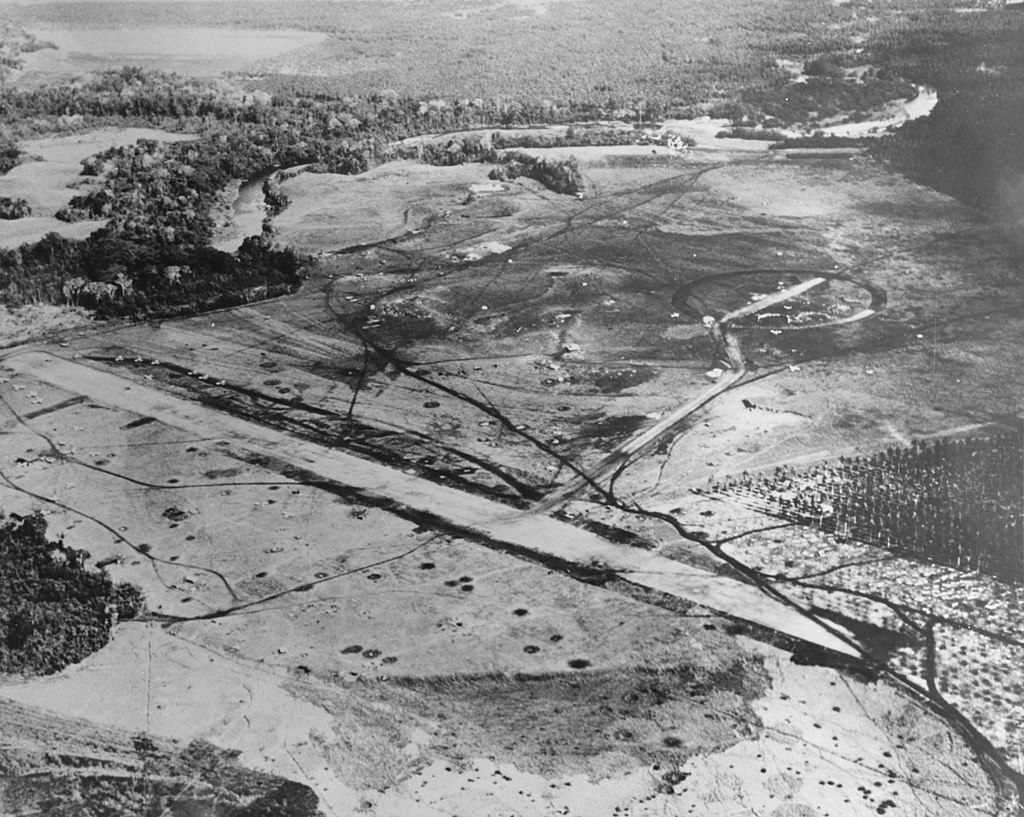

On 7 August 1942, the Americans landed on Guadalcanal, commencing the first Allied offensive operation in the Pacific. Initially, the skies over Guadalcanal were guarded by aircraft-carrier based Wildcats, which were soon joined by Wildcats from the US Marine Corps; finally, in the second half of August, these forces were bolstered by the USAAF’s 67th Fighter Squadron. The unit had a complement of thirty-eight fighters, the vast majority of which were P-400s. The squadron was redeployed to the island gradually, as Henderson Field was expanded and new satellite airfields built. On 21 August, the first five Airacobras with additional long-range fuel tanks took off from New Caledonia and, flying behind a B-17 from the 11th Bombardment Group, reached Efato, and then, after topping up fuel, flew on to Espiritu Santo. At dawn the following day, the pilots of the 67th Fighter Squadron continued their journey, covering another 350 kilometres and landing at Henderson Field.

Henderson Field, end of August 1942. Photo made by the aeroplane from USS Saratoga

Here, the initial intention was to use the P-400s as interceptors in support of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 223, whose Wildcats were fighting alone against overwhelming enemy forces. Unfortunately, the shortcomings of Bell’s became instantly apparent. Attempts at intercepting Japanese aerial forces quickly demonstrated that they flew higher than the Airacobras could climb. Air patrols could only be carried out at altitudes of up to 14,000 feet (4,300 metres), due to the unavailability of the British oxygen system, but even so, the lack of a turbocharger would not have allowed operations above 17,000 feet (5,200 metres). However, when enemy Zeroes descended to attack ground targets, the P-400s were able to effectively engage in battle.

The first fight

On 24 August 1942, P-400 pilots fought their first victorious skirmish against Japanese aircraft. That day marked the beginning of the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, which was the result of an attempt by a Japanese landing force to retake Henderson Airfield. A series of clashes flared up in the air, with aircraft carrier-based fighters from both sides playing the leading role. Henderson Field obviously became one of the main targets of Japanese air strikes. The mechanics and pilots of the 67th Fighter Squadron were initially caught off guard, and only the whirr of engines made them aware of the impending danger. The airfield was first strafed by A6M2 Zeroes from the aircraft carrier Ryujo. Two pilots managed to take off despite the attack: Capt. Dale D. Brannon and 2nd Lt. Deltis H. Fincher. Other Airacobras were prevented from taking off by bombs dropped by incoming B5N2 Kates. Brannon and Fincher, however, managed to intercept and jointly shoot down one of the Zeroes, which was just gaining altitude following a ground-level attack. As the pilots of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 223 reported shooting down thirteen Kates and seven Zeroes, Brannon and Fincher’s victory may seem modest, but it was the first victory achieved on a P-400 over Guadalcanal.

Airacobras on Guadalcanal, Summer 1942

Although the outcome of the Battle of the Eastern Solomons was by no means a tactical victory for the Americans, the Japanese lost in the operational sense. Despite the involvement of considerable forces and a display of great commitment, the Japanese could not retake Henderson Field, and their defeated troops were forced to retreat into the jungle.

The biggest battle

The P-400’s biggest battle with the Zeroes took place six days later, on 30 August 1942. When single-engined enemy aircraft were detected approaching Guadalcanal, it was assumed that these were dive bombers escorted by Zeroes. Wildcats from Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 223 were therefore scrambled to intercept the fighters, while the P-400s were instructed to focus on the Japanese bombers. However, it soon became apparent that the expedition consisted solely of Zeroes from the aircraft carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, which had been stationed at Buka on Bougainville for a few days. Their objective was to carry out a sweep over the island and hunt down American aircraft. The Airacobras flew in two formations. A section of four P-400s patrolled below, and two sections of seven Airacobras patrolled above. Six Zeroes (presumably from Zuikaku) detached themselves from the formation and attacked four low-flying Airacobras, shooting down all of them. When the Japanese struck the two remaining sections, the helpless pilots of the 67th Fighter Squadron formed a defensive Lufbery circle. But this was not a good tactic against the Zeroes. The manoeuvrable Japanese fighters joined the wheel and – as the Allied pilots later reminisced – after a while there were more of them in the circle than Airacobras. Fortunately, the Wildcats made their presence known, distracting the Japanese. The P-400 pilots took advantage of the confusion and fled into the clouds floating below. The co-author of the first victory achieved on a P-400, Capt. Dale Brannon, reported two confirmed kills (both Zeroes) in the encounter; as it turned out, this was the official outcome of the battle and was included in the summary in USAF Historical Study 85. The squadron book mentions four confirmed victories and three probables, while Frank Olynyk states that reports awarded five confirmed kills and two probable. It is possible that these optimistic reports were written to cheer the pilots’ hearts, because there is no escaping the fact that the clash ended in a spectacular defeat of the P-400. But the expedition also ended very badly for the Japanese, for no less than ten Zeroes failed to return to Buka airfield on Bougainville. However, the perpetrators of this bloodbath were primarily the pilots of the Marine Wildcats, who claimed fourteen victories. In truth, if not for them, the Japanese would most likely have had ample time to search for survivors and complete the massacre of the Airacobras.

After the battle, the black humour of the airmen fighting on Guadalcanal led to a unique decoding of the USAAF’s “P-400” designation. The conclusion was that the P-400 was actually a P-40, only with a Zero (“0”) on its tail. Whereas the command of the combined USAAF and USMC aerial forces on Guadalcanal, officially named the Cactus Air Force, decided that the Airacobras would from then on perform only three types of tasks: reconnaissance, attacking ground targets, and escorting the Marines’ Dauntlesses. Further, a special procedure – very humiliating for fighter pilots – was adopted to be applied in the event of the detection of an approaching Japanese air raid. While the Wildcats were to take off to intercept the enemy force, all airworthy Airacobras were to take off and fly in the exact opposite direction. Their pilots were to wait out the battle in the air somewhere far away, so as to prevent the aircraft being destroyed on the ground. The problems with the P-400 were communicated clearly and by probably all commanders in the South Pacific. There was unanimous demand for the delivery of Lightnings to Guadalcanal, and indeed it was the Airacobra’s shortcomings that resulted in the P-38-trained 339th Fighter Squadron being redirected to the island. Although it was originally planned to deploy the unit to New Guinea, the Airacobras’ resounding defeat helped convince staff to use it in support of the defence of Guadalcanal. Later, the squadron would spectacularly end the career of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto.

To the ground attack duties

Meanwhile, in September 1942, the 67th Fighter Squadron commenced missions against ground targets. P-400 pilots with underslung 500-pound bombs attacked groupings of Japanese troops. Very quickly it became apparent that the Airacobras excelled at attacking small Japanese surface vessels. During this time, the Japanese were making every effort to ensure a continuous supply of ammunition, food, fuel and reinforcements to their units on Guadalcanal. The Americans dubbed the uninterrupted stream of Japanese shipping the “Tokyo Express”. From these vessels, cargo and soldiers were taken ashore in smaller boats and barges. And it was on these small units that the P-400 pilots focused. It soon became obvious that that this was the role of a lifetime for the unsuccessful, half-baked fighter. Concentrating the most powerful on-board weaponry in the aircraft’s nose resulted in a high accuracy of fire. Well armoured and with self-sealing fuel tanks, the Airacobras could not be shot down from the ground with any odd machine gun. The effectiveness with which the 67th Fighter Squadron set about destroying the Japanese supply chain was such that hell froze over and the defenders of Guadalcanal made an astonishing demand: “Give us more Airacobras!”. P-400 pilots even developed a special dive-bombing technique. Something for which the Bell fighter had never been envisaged. Diving from a much lower altitude than the Dauntlesses, the Airacobras – not equipped with aerodynamic brakes – would swoop down on targets at high speed, release their bombs and, at full throttle, their nearly blinded by the strain, pull up just above ground to escape the anti-aircraft fire. Typical targets for the P-400s were infantry concentrations, artillery, anti-aircraft guns, enemy bivouac sites, ammunition and fuel depots, and barges and boats in coastal waters.

P-400 Airacobras on Guadalcanal, 1942

A critical and, indeed, pivotal moment in the fighting for Guadalcanal was the Battle of Bloody Ridge. On 12 September, Japanese reinforcements under the command of General Kawaguchi, which had only just landed on the island, launched another attack – the most powerful yet – towards Henderson Field. On the night of 13–14 September, they assaulted the hill that was later named Bloody Ridge and soon reached the airfield boundary. On the morning of 14 September, the P-400s launched three furious attacks against the Japanese soldiers deployed in the open. This caused such losses and confusion among the Japanese infantry that the decimated survivors fled into the jungle. General Geiger later declared that these three Airacobra attacks had saved the entire Guadalcanal campaign.

New squadrons and new planes

In late September/early October 1942, a new squadron – the 339th Fighter Squadron – arrived on Guadalcanal; in the long term, it was to operate Lightnings, but it temporarily had to make do with the P-400s and P-39s available at Henderson Field. That is where the replacements – P-39Ds, Ls and Ks – finally arrived. Some were transported to the island by the pilots of the 68th Fighter Squadron, which was also attached to the Cactus Air Force. The new Airacobras had working oxygen systems, while the P-39Ks and Ls were significantly slimmed down and equipped with a new Allison engine with much greater power (1,360 hp versus 1,150 hp in the P-400). It was originally planned that the new P-39s would finally be used for fighter operations, but General Vandergrief decided that all Airacobras would continue to support the ground troops, as they had become invaluable on the island in this role.

P-400 Airacobra „white 13” „Hells Bell”, BW151, 67FS/347FG, pilot Lt. Robert M. Ferguson, Guadalcanal, August-November 1942. See Wolf William, “13th Fighter Command in World War II” p. 58 & 50.

P-400 Airacobra „white 13” „Hells Bell”, BW151. Photo: iModeler

In November 1942, the pilots of the 67th Fighter Squadron had their first opportunity to successfully engage in air combat since the fateful encounter of 30 August. On the afternoon of 7 November, the Americans detected another “Tokyo Express” approaching the northern coast of Guadalcanal. It was made up of eleven ships carrying some 1,300 Japanese soldiers. Every aircraft stationed at the already expanded hub of airstrips around Henderson Field was ordered to take off. The plan was for eight P-400s and P-39s from the 67th and 339th Fighter Squadrons, armed with 500-pound bombs, to attack the ships first. The raid was then to be continued by seven SBD Dauntlesses from VMSB-12s carrying 1,000-pound bombs, and three TBF-1 Avengers from VT-8 carrying underslung torpedoes. This force was to be escorted by twenty-three F4F-4 Wildcats from VMF-121. Yes – that is exactly how powerful the Cactus Air Force was at the time. During this period, the number of operational aircraft on Guadalcanal fluctuated between fifty and sixty. But the plan went a bit awry from the start, as the take-off of the Airacobras was delayed. Thanks to this, however, the P-400 and P-39 pilots arrived on the scene just as A6M2-N Rufe seaplanes, which along with F1M2 Pete biplanes were tasked with providing air cover for the convoy, began to creep up on the Wildcats. All this took place at a fairly low altitude, and the Airacobras had no trouble catching up with the Japanese fighters. 1st Lt. Robert M. Fergusson from the 67th Fighter Squadron reported shooting down one Rufe, while his colleagues from the 339th Fighter Squadron, flying on P-39s, reported downing two more Rufes and two Petes. Officially, however, the Airacobra pilots were credited with three victories, including Fergusson’s.

Farewell “400”

As it turned out, this was one of the P-400’s last actions on Guadalcanal. By mid-November, there were no more airworthy P-400s on the island. Later, some individual aircraft were repaired, but in February 1943 the decision was taken to withdraw the type completely from combat in the South Pacific. This coincided with the final defeat of the Japanese and the withdrawal of the remainder of their troops from Guadalcanal.

During the fighting in the Solomon Islands one Airacobra pilot – William F. Fiedler –became an ace. However, he achieved all five of his victories while operating the P-39D and P-39N as a pilot of the 70th and 68th Fighter Squadrons. Dale D. Brannon from the 67th Fighter Squadron gained the highest number of kills on the P-400. As was described above, in two flights in August 1942 he downed two Zeroes on his own and one jointly with Deltis Fincher. He later scored one more victory, but by then he was flying a Lightning.

Check also:

A keen modeller since childhood. He is mainly interested in aviation from the times of the First and Second World Wars. He made about a hundred models, wrote a few books and several dozen articles.

Apart from modeling, he is passionate about history, not only the latest one, but also a very distant one. He loves to read journalism, scientific books and science fiction novels. All the time he grumbles that a day should be 50 hours long and he forces himself to go to sleep.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski