The Bell P-39/P-400 fighters were a perfect illustration of the old saying that “half a loaf is better than no bread”. The USAAC pushed them into combat only “for want of anything better”, when no other fighters were available. But all this was not so obvious from the start. The concept of the aircraft itself was innovative and imaginative, which initially led to high hopes. The Airacobras had a layout that was highly atypical at the time, with the Allison engine located behind the cockpit to make room in the nose for the large 37 mm calibre T9 cannon manufactured by Oldsmobile. The empty nose also allowed for the installation of an innovative three-wheel undercarriage. This arrangement had many advantages. The “tricycle” undercarriage made taxiing significantly easier.

Cartoon from the Airplane Manual

Placed near the centre of gravity, the engine should have theoretically increased manoeuvrability. Finally, the 37 mm cannon with fragmentation ammunition had devastating firepower. However, the P-39 also had significant drawbacks. The cannon fired slowly, with a steep trajectory, and was not suitable for use in high-speed duels with enemy fighters, where there was insufficient time for accurate aiming. To make matters worse, it was notorious for jamming after firing off two or three rounds – a feature that regularly made it unusable.

The atypical arrangement, with power being transmitted from the drive to the propeller through the entire fuselage, resulted in there being little space in the fuselage. Thus, the XP-39’s cockpit protruded quite high above the fuselage outline. During testing, it was decided to lower the canopy to reduce drag. As a result, the cockpit of the P-39 became very cramped, even claustrophobic. It soon became apparent that only pilots of very short stature could serve in squadrons equipped with Airacobras. Those were taller simply could not push themselves into the cockpit.

US Airacobra pilot shows his “workplace” to the Australian Beaufort pilot

Despite the high concentration of mass around the centre of gravity, good manoeuvrability proved impossible to achieve due to excessive load on the lifting surface. Worse still, the P-39’s wings were too small in relation to its weight. But the Airacobra’s biggest failing was that the engine was not equipped with a turbocharger. This was not Bell’s fault, however. The XP-39 prototype had had such a turbocharger, and at an altitude of 6,100 metres it reached a speed of 640 km/h. The decision to remove the turbocharger was taken by the USAAC command. This was justified by the brilliant observation that, since wars are fought on land, why must aeroplanes fly so high. How could such an argument be debated? Despite protests from Bell’s designers, the turbocharger disappeared from the P-39 design, never to return.

Bell XP-39 – Airacobra prototype with supercharger air intakes on the fuselage sides

In addition, the improvements necessary to bring the P-39 in line with the requirements of modern warfare, such as armour plating and self-sealing fuel tanks, served to overload the engine further. And so, instead of an agile interceptor fighter, pilots received a low-flying, slow and ungainly mule. Before the war broke out, this may not have been so clear to everyone. The shock was to come in the first months of 1942.

Orders from Europe

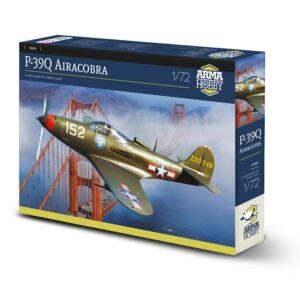

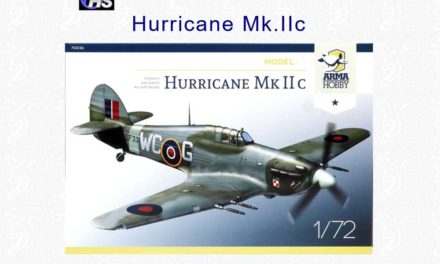

Classic Airacobra Mk I photo with 20 mm cannon and British markings of the No. 601 Squadron RAF

Although the P-39s were far from perfect, orders for the aircraft began to flow in to Bell from abroad. War erupted in Europe and belligerent France and Britain began to soak up military equipment like a sponge. The first 170 P-39s were ordered by the French, who, from September 1939 onwards, took whatever they could from the Americans. However, France fell before production was completed, and the order was taken over by the British – who immediately increased it to no less than 675 aircraft. One might be surprised that they ordered blindly, but the truth was a little different. For while the British were aware of the very good performance of the XP-39, they did not fully realise what the problem was with the serial P-39 without the turbocharger. They did, however, ensure that the new aircraft were adapted to the British military system. First of all, the 37 mm cannon, which was not used in the RAF, was replaced with the classic British 20 mm Hispano. British radios, a British oxygen system, and British sights were also fitted. Even the engine control system was modified. The throttle lever functioned in the same way, but the air-fuel mixture and propeller pitch control levers worked in the opposite direction. Swapping the Oldsmobile main armament for the accurate and quick-firing Hispano was an excellent move, but in truth the most important problems dogging the intricately designed aeroplane, with the engine behind the cockpit, remained.

To battle over Pacific

The new aircraft, named the Airacobra Mk.I, was sent to test units, and to No. 601 Squadron RAF, which was fighting over the English Channel. The British quickly found out the unpleasant truth, namely, that the Airacobra was not suitable for combat as a fighter. The main reason, of course, was its inability to fight at medium and high altitudes. As a result, 212 Airacobra Mk.Is were pushed as lend-lease to the Soviet Union, where aerial combat took place mainly at very low altitudes and where Bell’s fighter could thus prove its worth. A total of 179 British Airacobras were taken over by the Americans, who renamed the aircraft – previously modified to RAF standards – as the P-400. The rapid advance of the Japanese in the Pacific theatre and the colossal losses suffered there by the USAAC meant that the P-400 was sent to the front line immediately, without making practically any adjustments. In fact, they only received American stars before being packed onto transports. Although this was not entirely planned, the P-400s initially found their way to specific USAAC squadrons, in which they played a predominant role for some time. Generally speaking, they were all sent to the Pacific, however some eventually ended up in Australia, where the nucleus of the Fifth Air Force, which fought in New Guinea, was being formed, while others reached the South Pacific and went on to take part in the battles for Guadalcanal as part of an Army and Naval Aerial ensemble known as the Cactus Air Force.

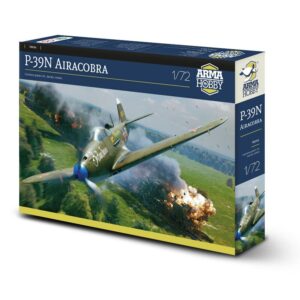

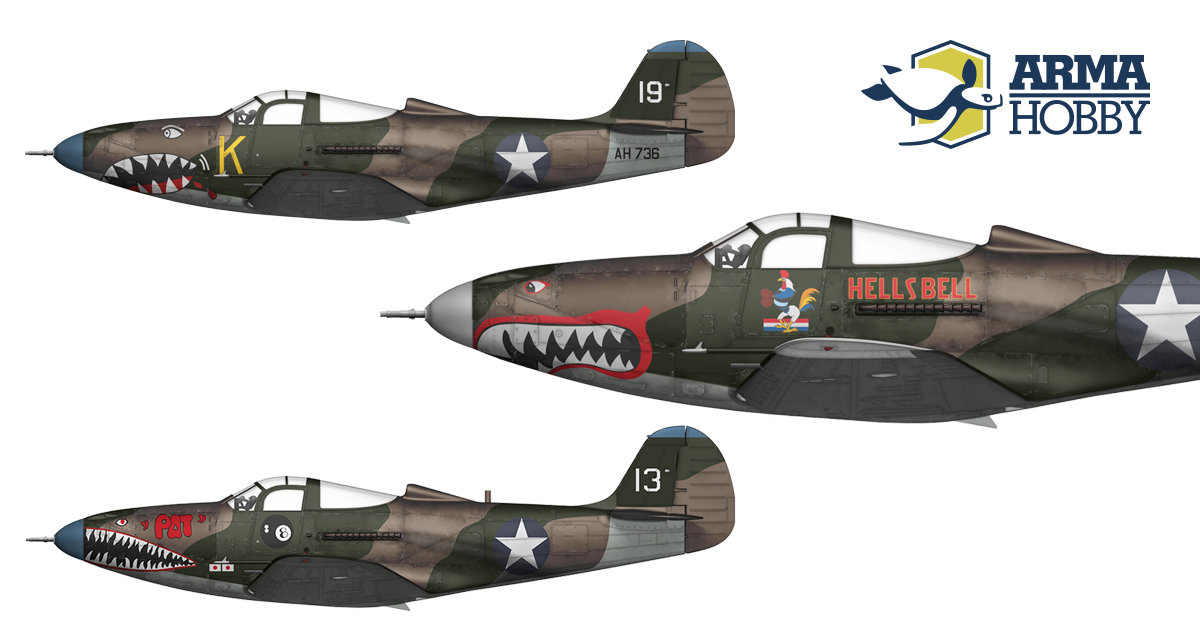

American P-400 Airacobra with British serial BW 117 and British camouflage. Note the 12-tube exhaust, typicall for this version. Plane was assigned to the 5th Air Force (5th AF), 35th Fighter Group (35th FG), 40th Fighter Squadron (40th FS) at Port Moresby and was piloted by 2nd Lt. Edward J Gignac.

Richard Suehr, an ace with the 35th Fighter Group who fought on the P-400 over New Guinea and scored the first of his five victories on the type, recalled that the Airacobra was a small, sleek and beautiful aircraft that had a number of innovative features. First and foremost, of course, he was referring to the placement of the engine behind the cockpit and the modern three-wheel undercarriage. Objectively, the cockpit was cramped, but Suehr was very short (some 150 cm tall), and for him it was very comfortable. All of the instruments were logically laid out and easily accessible. Compared to other fighters of the period, the P-400 offered excellent visibility. However, pilots were moderately enthusiastic about the way the sight was mounted. During a forced landing, it was easy to smash one’s head against it. The four-channel UHF radio was of very good quality, but generated noise that was tiring to pilots. Whereas the 1,150 hp Allison engine was quite robust, and not prone to breaking down. Immediately after being switched on, the engine, with its system of complex gears, jerked the aircraft mercilessly, but once it reached its operating rotational speed, it worked quite smoothly. The whole complex power transmission system was surprisingly very robust and did not suffer from breakdowns. Finally, the tricycle undercarriage was perfect for taxiing around airfields. However, it was not possible to manoeuvre on the ground for too long with the engine running, as the Allison had a tendency to overheat. The rate of climb after take-off to an altitude of some 12,000 to 13,000 feet (3,650 to 3,950 metres) was not bad.

Airacobra in flight over New Guinea

But higher up, the turbocharger-less P-400 lost agility, and in fact took an eternity to get up to 20,000–25,000 feet (6,100–7,600 metres), at which elevation the Japanese loved to operate. And once this ceiling was laboriously reached, the Airacobra was unable to catch up with anything – even the “Betty” bomber. The only sensible tactic was a surprise attack and a diving escape. In a dive, the P-400 was second to none, falling towards the ground like a brick. The tactic of inciting confusion at altitude and then diving was used frequently. All this was intended to lure Japanese pilots into accepting low-altitude combat, where the Airacobra regained its vigour. Suehr, like the majority of his colleagues, complained that the engine power (1,150 hp) was insufficient in relation to the weight of the heavily armed and quite well armoured aircraft, additionally fitted with heavy, self-sealing fuel tanks. According to Suehr, these characteristics predestined the P-400 to be a great aeroplane for attacking ground targets.

John Thompson, who fought on the P-400 at Guadalcanal with the 67th Fighter Squadron, had very similar memories of the fighter’s weak and strong points. Already the very first dogfight with Japanese Zeroes brought home to the American pilots that the Airacobra was no match for the enemy. In this skirmish, Thompson was immediately outmanoeuvred by one of the A6M2s, which proceeded to fire at the tail end of his aeroplane. Some of the bullets lodged in Thompson’s rear armoured window, while one passed through, wounding him in the shoulder. Another hit the engine regulator. Nevertheless, Thompson managed to cheat death, diving and successfully landing at Henderson Field. After a couple of attempts to take the fight to the Japanese in the air, all the Airacobras were instructed to focus on ground and sea targets. In this role, the P-400 was excellent. Thompson was hit several times by anti-aircraft machine guns, but the glass and armour plating – plus the self-sealing fuel tanks – held firm, allowing him to return safely to Henderson Airfield.

Cactus Air Force Airacobras on Guadalcanal

In his opinion, excellent visibility from the cockpit played a great role in attacks on ground targets. Being short, Thompson remembered the cockpit as quite comfortable, with all the instruments spaced ergonomically, clearly visible and within easy reach. Starting the engine, when the Airacobra shook terribly, was not a very pleasant experience. The engine and gears had to pick up speed for the aircraft to stop feeling like it was going to fall apart. Thompson, like Suehr, remembered that the Allison easily overheated, and if you stood on the runway for too long, you had to turn it off. Pilots could engage in a more or less even fight with enemy aircraft at altitudes of up to 12,000–14,000 feet. It was impossible to fly higher, not only because of the lack of a turbocharger, but also because oxygen masks compatible with the British oxygen system were never transported to Guadalcanal. The low fuel supply was also a problem. It was enough for two hours of flying, which was always too little for intercepting enemy aircraft and conducting patrols. However, the amount was sufficient for attacking ground targets located on Guadalcanal itself.

Thompson was highly critical of the radio station. In order for anything to be heard over it with the engine howling, it had to be set very loud, in which case the pilot’s ears were blasted with a cacophony of unpleasant squeaks and squawks. Thomson was convinced that flying on the P-400 permanently damaged his hearing, and he was forced to use a hearing aid in his old age. On the other hand, he was very positive about the armament. The 20-millimetre cannon, although sporting less firepower, had a better bullet trajectory, greater accuracy, a four times greater supply of ammunition, and a higher rate of fire than the 37 mm cannon of the P-39. In addition to the cannon, the P-400 had an imposing battery of four 0.303-inch Brownings in the wings and two 0.5-inch Brownings in the nose. It was, according to Thompson, the most heavily armed Allied aircraft on Guadalcanal. He particularly remembered attacking Japanese troops in the critical encounter of the campaign – the Battle of Bloody Ridge. The P-400s killed hundreds of enemy soldiers with their on-board armament, resulting in the collapse of Japanese attempts to capture Henderson Field. There was only one single problem with the 20-millimetre cannon on Guadalcanal. Namely, the airmen of the 67th Fighter Squadron were able to use it very infrequently because there was little ammunition for it on the island. As fighters, the P-400s hardly performed in the Guadalcanal campaign, but their role in supporting the Marines on the islet cannot be overestimated. Thompson remembered that the P-400s were used “until they were worn out” and simply no longer operational.

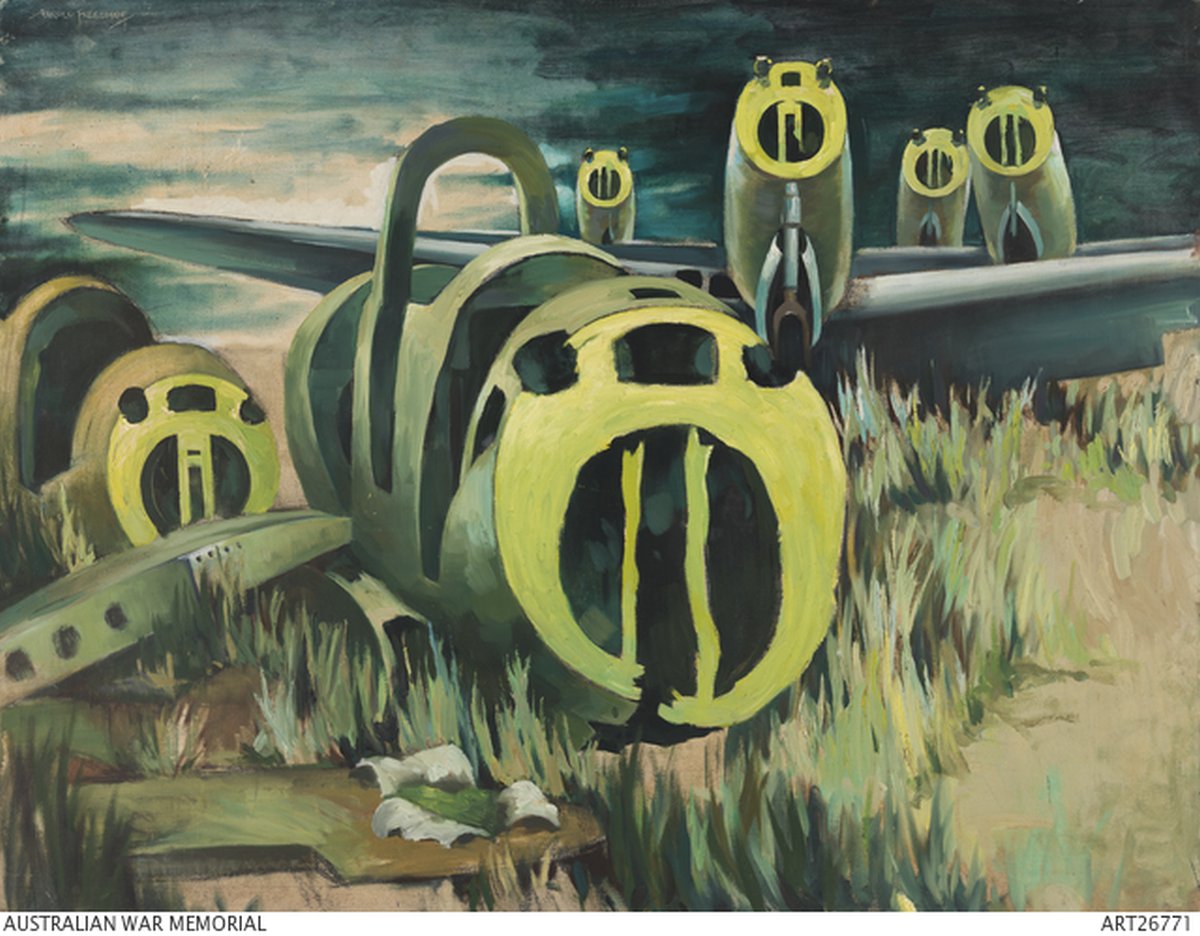

Amazing Harold Freedman’s oil painting showing old Airacobras dumped in Port Moresby. Freeman was official war artist of the Royal Australian Air Force

If we accept that the Airacobras were transitional fighters in the USAAC, then the P-400 was a transitional version of a transitional aircraft. Significantly, it was used only by a few USAAC squadrons in the early stages of the war, and disappeared for good from the last combat unit in the late summer of 1943. However, it was the P-400 pilots who shouldered the burden of stopping Japanese offensives in two strategically important directions – in New Guinea, during the defence of Port Moresby, and on Guadalcanal, during the defence of Henderson Field. There are only a few instances where ground commanders have concluded that an attack launched by a handful of fighter aircraft against enemy troops resulted in the success of an entire campaign. And this is exactly how the P-400 pilots of the 67th Fighter Squadron who fought on Guadalcanal were assessed. More on the topic soon, in Tomasz Gronczewski’s next article!

Check also:

A keen modeller since childhood. He is mainly interested in aviation from the times of the First and Second World Wars. He made about a hundred models, wrote a few books and several dozen articles.

Apart from modeling, he is passionate about history, not only the latest one, but also a very distant one. He loves to read journalism, scientific books and science fiction novels. All the time he grumbles that a day should be 50 hours long and he forces himself to go to sleep.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski