“Cactus” was the code name for the American air base on Guadalcanal, an island that was fought for with great intensity in the second half of 1942. For the first time in the war, the combined forces of the US Marine Corps, US Navy and USAAF stopped a Japanese invasion. This would not have been achieved without a combined aerial force – the Cactus Air Force (CAF).

This informal unit operated from the summer of 1942 to the beginning of 1943, when it was incorporated into Thirteenth Air Force.

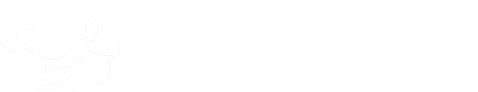

Cover picture: “Let’s go gang”, clash of Wildcats and Airacobras with Japanese Strike aircraft at Guadalcanal, November 11th, 1942. Artwork Piotr Forkasiewicz.

Prelude

When in July 1942 American aerial reconnaissance discovered that an airfield was being constructed on the island of Guadalcanal, at the time occupied by the Imperial Army, the Allies became aware of the threat which this posed to supply routes from the USA to Australia. At the time, their forces were being driven from New Guinea and the Solomon Islands (under Australian administration). The Allies retained control over the New Hebrides, Fiji and American Samoa. And although New Caledonia belonged to the Vichy government, the local French administration had no choice and accepted an American protectorate.

On 7 August 1942, the US Navy commenced its counter-attack. A team of aircraft carriers hit Guadalcanal and neighbouring Tulagi, and the 1st Marine Division quickly captured both islands.

Japanese expansion, Summer1942. Map – wikipedia.

The First Engagement

The Japanese could not ignore the American attack on Guadalcanal. Before the Imperial Army’s reinforcements arrived on the island, they launched a naval air force strike. However, the first aircraft – reconnaissance G4M-1 Betty bombers – failed to hit their targets. They had been preparing to attack land-based targets at Milne Bay in New Guinea, and were sent ad hoc, as a stopgap assault force. The next day, the Japanese sent twenty-seven bombers armed with torpedoes, escorted by 15 A6M2 Zero fighters.

G4M “Betty” approaches US fleet, Guadalcanal August 8th,1942 r. PhotoWikipedia.

But when the bombers emerged from the clouds at around 13:15, they were intercepted by eight F4F-4 Wildcats from Fighting Squadron 5, which was based on the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga. Lieutenant James J. “Pug” Southerland II became the first Allied flier to gain a kill in the Guadalcanal campaign, shooting down the leading bomber, piloted by Petty Officer 1/c Shisuo Yamada. The Japanese gave as good as they got, and bullets from the machine guns of the remaining bombers soon hit Southerland’s armoured windscreen and the rear of the fuselage. Pug turned his attention to another bomber. There was little room for manoeuvre, especially as his opponent was getting ready to launch a low-level torpedo attack. Despite the difficulties, Southerland managed to bring down another bomber, piloted by Petty Officer 1/c Yoshiyuki Sakimoto; it was then that the Japanese escorts finally intervened. Fifteen Zeroes from the elite Tainan Kokutai (Tainan Air Group) immediately shot down two Wildcats and engaged in a fierce battle with the others. But the American pilots did not give up and, using the Thach weave, they put up a stiff resistance.

F4F-4 Wildcat „black F-12” BuNo. 5192, pilot Lt. James „Pug” Southerland II, VF-5/USS Saratoga. On 7th August 1942, this aeroplane downed the first Japanese bomber over Guadalcanal before Saburo Sakai himself shot it down in epic lonely combat against a flight of “Zeros”. Aeroplane colours are discussed in “First Team and Guadalcanal” (see recommended reading at the end of text). See info on Pacific Wrecks link. Artwork by Zbyszek Malicki.

It was then that Pug fought the fight of his life. Having used up all of his ammunition on the bombers, he was pitched into a fight with the legendary Saburo Sakai – an ace with fifty kills. Southerland knew that he could not harm the Zeroes without any ammunition. He therefore lowered his seat in order to better hide behind the armoured plate, and manoeuvred in such a way so that enemy fire hit the rear of the fuselage. The Zeroes attacked in pairs from different directions, and for five minutes he managed to successfully determine which of the two would attack first. Just before the Japanese pilot opened fire, he would turn sharply towards him and thus avoid being hit in the engine or cockpit.

As time passed, Saburo Sakai became increasingly frustrated with Pug’s manoeuvres. He could not believe that the Wildcat was still fighting after receiving so many hits. He was full of admiration for the courage and determination displayed by the most difficult opponent he had ever met. Finally, he took aim at the fighter’s wing root and opened fire with the last of his 20 mm cannon shells; the American aircraft simply exploded.

However, this was not the end of Southerland. With the aircraft literary falling apart mid-air, he somehow opened the cockpit and slipped out. And then the holster of his Colt caught on the canopy slide rail. We do not know how he managed to free himself from this deadly trap and open his parachute at a minimal height. After a few days he was rescued by natives and sent back to the aircraft carrier. The wreckage of his Wildcat – with the Colt still in the cockpit – was found many years later in the thick brushwood of Guadalcanal. Saburo Sakai did not enjoy his victory for long, however. During the same flight, he was seriously injured while attacking SBD Dauntless naval dive bombers, which he mistook for fighters, and, with great difficulty, losing consciousness several times, only just managed to reach Rabaul.

Wounded Saburo Sakai after return from Guadalcanal, August 8th, 1942. Photo Wikipedia link.

The attack of the G4M-1 bombers was repelled by the carrier-borne Wildcats and the anti-aircraft artillery of the cruisers which were escorting the landing. A destroyer was hit by a torpedo, while a damaged bomber rammed one of the transport ships. The next night, a group of Allied cruisers was routed by a Japanese task force during the Battle of Savo Island. The defeat forced the American fleet of aircraft carriers and transport ships to withdraw to the open ocean, beyond the range of enemy reconnaissance, leaving the Marines without any naval protection. The siege of the island began.

Wildcats and Cobras at Guadalcanal

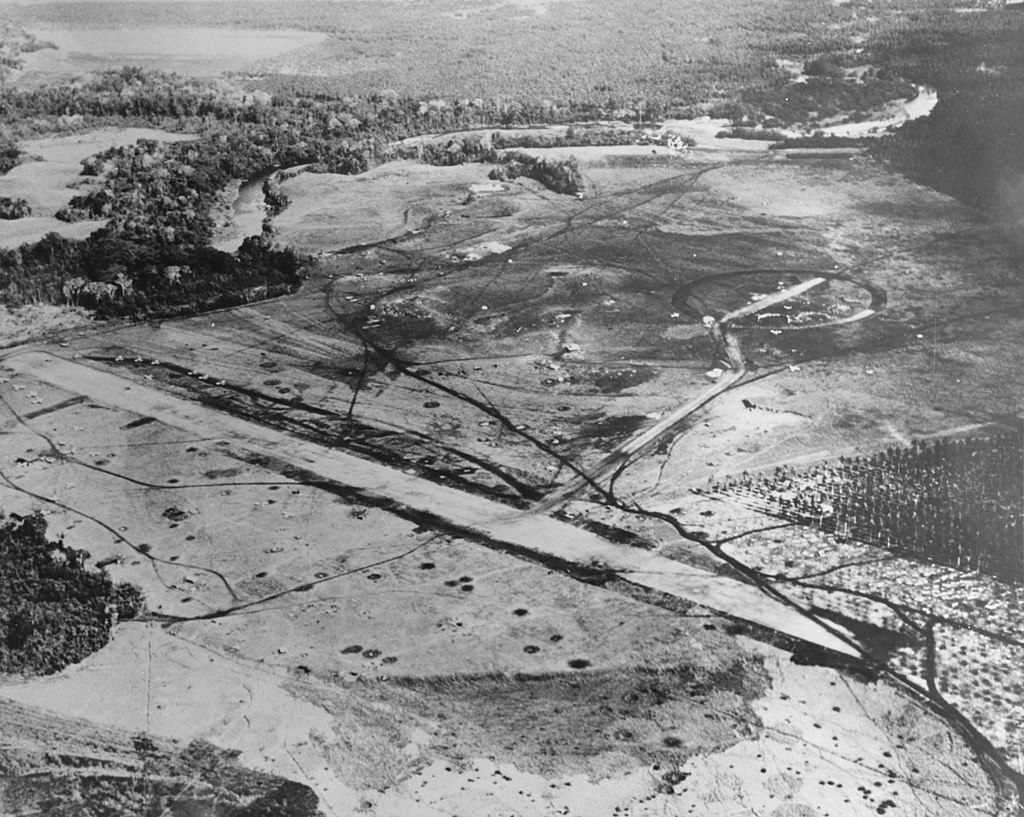

At the airstrip, work proceeded with feverish haste. What the Japanese had been unable to do for more than a month, the Marines completed – albeit using machines – within two weeks. The airfield which they built was named after Lofton Henderson, the commander of a Marine bomber squadron who had perished in the Battle of Midway.

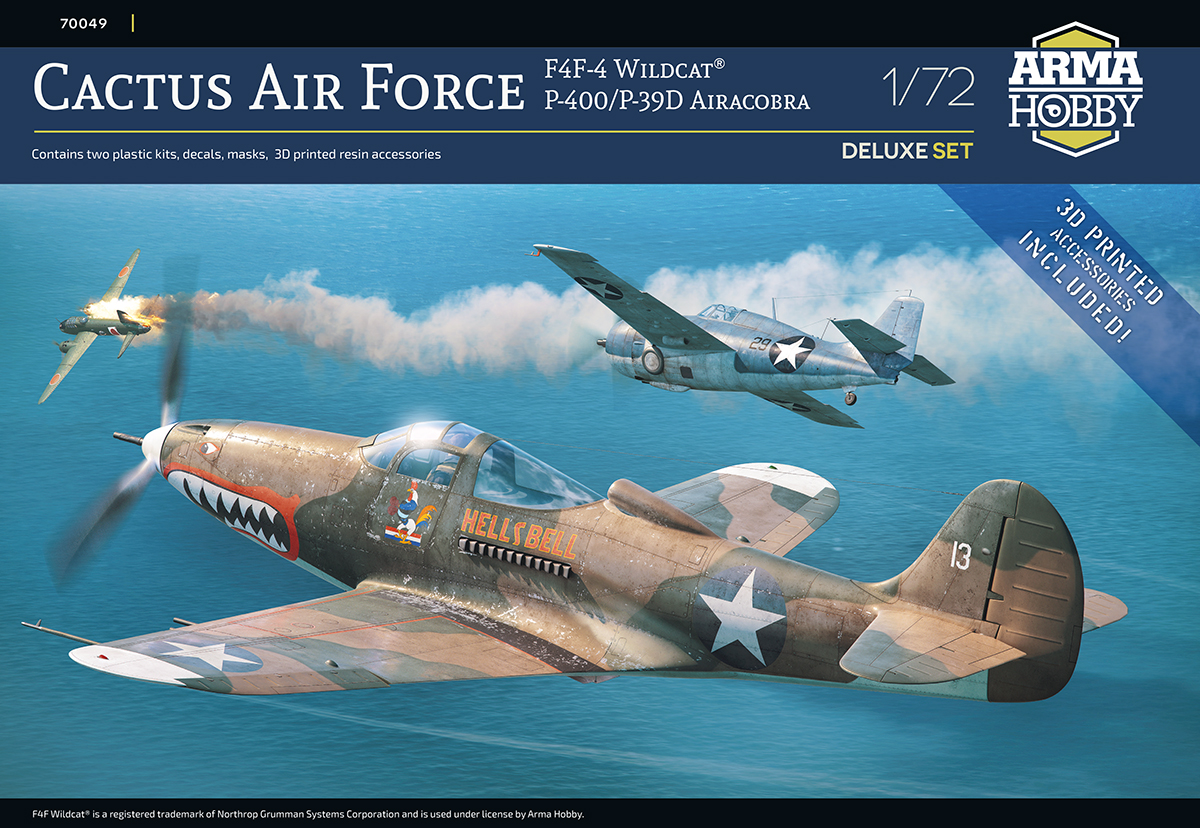

The first Marine aircraft – SBD bombers from VMSB-232 and F4F-4 Wildcat fighters from VMF-223, transported on board the aircraft carrier USS Long Island – landed there on 20 August. Two days later, they were joined by P-400 Aircobras from 67th Squadron USAAF. This method was used regularly to supplement the Cactus Air Force. From time to time, escort carriers would supply complete Marine aerial units from Samoa or New Caledonia, two important bases which supplied the Solomon Islands front that included Guadalcanal. The island became home to a unique “fighter pilots’ commune”. Available pilots from various USMC units flew on combat missions on aircraft that were available at any given time. Each Wildcat received its own individual number, and the “100” mark was exceeded well before the end of the campaign. Captain Joseph Foss had to change his original number “13” to “53”, because when he arrived on the island in early October it was already used by Captain Marion Carl’s second aeroplane (he had two “13s”, one after the other).

Henderson Field, late August 1942. Photo taken by aircrew from USS Saratoga.

The USAAF operated somewhat differently. Each rear echelon archipelago had its own separate Fighter Squadron, which was responsible for its defence. The most important was the 67th Fighter Squadron, which was located on New Caledonia, where it administered aerial operations. It arrived at the French colony in March 1942, together with crates containing forty-five P-400 “Caribous” supplied by the RAF and painted in British land camouflage, and two P-39D Aircobras. The pilots assigned to the unit had little operational experience, and none at all on the P-39, but after assembling their aircraft they commenced training and started to patrol the airspace over the island. They were scattered between various airstrips, the best known of which was Patsy Field (whose crew was called the Patsy Flight). Initially, fifteen aircraft were sent to Guadalcanal in two groups. After a flight with stops on Efate and Espiritu Santo, the Cobras, having covered hundreds of miles over the sea, were led to their destination by a B-17 Flying Fortress. Later, elements of squadrons stationed on the other archipelagos were redirected to Guadalcanal. Even then, however, the 67th Fighter Squadron was the command unit and provided logistical support.

From the beginning of September, Guadalcanal had its own radar station, which was operated by the Marines.

P-400 Airacobra „white 12”, BW156, pilot Lt. Richard Johnson 67FS/347FG „Fancy Nancy”, Guadalcanal August-September 1942. See photo in Wolf William, “13th Fighter Command in World War II” p. 45. Artwork byZbyszek Malicki.

Fighters and Bombers

The Aircobras were poorly adapted to operating from field airstrips. The undercarriage with the front wheel made it very difficult to land even on good surfaces. The aeroplane itself, without the second engine compressor stage, lacked power at higher altitudes. However, the 20 mm (P-400 and P-39D-1) and 37 mm (other versions) cannon, shooting through the propeller axis, was excellent for strafing ground targets. The Aircobra could carry 250- and 500-pound bombs, and even 375-pound depth charges, which were used to murderous effect. Tongue in cheek, pilots of the first Aircobras from the 67th Fighter Squadron referred to themselves as the “Jagdstaffel” (German for fighter squadron), although they achieved their successes primarily as dive bombers. Time and again, they provided invaluable ground support to the Marines. Their biggest success consisted in repelling an attack launched on their base on 14 September 1942, when the Marines were ejected from Edson’s Ridge, which towered over the approach to Henderson Field. After dropping their bombs, three P-400s strafed some 2,000 Japanese infantry soldiers from a height of no more than 25–30 feet (!). They were so effective that the entire attack collapsed, and the Marines regained their positions. For their role in the fighting, General Vandegrift, the commander of Allied forces on Guadalcanal, awarded Captain Thompson with the Navy Cross (the highest US Navy medal), and lieutenants Brown and Davis with the Silver Star. General Geiger (commander of the Cactus Air Force) discreetly awarded them with the last bottle of whisky from his own stocks.

P-400 Airacobra on Guadalcanal, Summer 1942.

The Marines’ aerial detachment was occupied primarily with the provision of fighter defence for the island. The airfield and supply routes were under constant attack by Japanese aircraft from New Britain – G4M-1 Betty bombers escorted by in the A6M2 Zeroes. But the Zeroes, hitherto unmatched in the skies of South-East Asia, found the Marine Corps pilots a worthy opponent. The rules of warfare introduced by Colonel Bauer turned out to be effective. The Wildcats, operating as teams, made use of the advantage of “situational awareness” (Australian coastguardsmen on the Solomon Islands, the so-called Coastwatchers, provided advance information of incoming aeroplanes) and, guided in by radar, waited for the enemy in the air. The advantages of Japanese naval aircraft, that is, range, speed and manoeuvrability, had been achieved at the cost of heavier armour and self-sealing fuel tanks. Properly hit, the Betty became a “flying lighter”, while the Zero would explode in the air. Whereas the Wildcat was difficult to shoot down. Joe Foss claimed that he only once saw an exploding F4F-4. American losses were the result of engine damage or pilot death.

In addition to aerial attacks, the enemy regularly attacked Henderson Field with long-range naval artillery. Japanese ships would sail up to the coast at night and, under cover of darkness, make life as unpleasant as possible for the airfield’s garrison. When morning came, they would flee beyond the reach of the Marine pilots. Until the US Navy sent in major reinforcements, nothing could really be done to counter the problem.

Although the first Marine Corps units were rapidly consumed in the fighting, by October, and especially after the arrival of VMF-121, which went on to become the most effective Marine squadron of the entire campaign, the situation began to stabilize.

Captain Joe Foss – The Deadliest Wildcat Pilot in the Marine Corps

Two Aircraft Carrier Battles

The deadlock on Guadalcanal lasted for several months. Japanese naval aviation, stationed in New Britain, was unable to defeat the Cactus Air Force. This forced the Fleet to come to its assistance. However, the previously mentioned bombardment of Henderson Field by the main artillery of the Japanese battleships did not bring about the expected result. Although losses were severe, the airstrip remained active. The Japanese battleships moved from north to south along the Solomon Archipelago, between two rows of islands known as the “slot”. The American aircraft carriers protected the approaches to Guadalcanal from the ocean. It was there that they twice clashed with their Japanese counterparts.

The Battle of the Eastern Solomon Islands

After the Battle of Midway, where four of the six large aircraft carriers of the Imperial Fleet were lost, the last two such vessels remaining in the Japanese Navy (the Zuikaku and Shokaku) were sent to face an American task force comprising USS Enterprise and USS Saratoga; the third ship, USS Wasp, did not take part in the battle). The purpose of the operation, which was carried out towards the end of August, was to deliver reinforcements to Guadalcanal. The supply group was escorted by the light aircraft carrier Ryujo. The Battle of the Eastern Solomon Islands (24–25 August 1942) was the first exchange of blows between aircraft carriers in this campaign.

The engagement was commenced by the carrier Ryujo, which launched an attack on Henderson Field that was, however, completely repulsed by the Cactus Air force (twenty-one enemy aircraft were shot down). While the assault was under way, American carrier-based aeroplanes sunk the Ryujo. In the following clash between large aircraft carriers, the USS Enterprise was damaged. The result of the battle was favourable for the US Navy. One Japanese aircraft carrier was sunk and nearly ninety enemy aeroplanes destroyed for the loss of twenty-five aeroplanes.

Immediately after the battle, however, the activity of the American aircraft carriers decreased. The USS Enterprise and USS Saratoga had to be sent for repairs to Pearl Harbor (the latter after being hit by a torpedo on 31 August), while USS Wasp was sunk on 15 September 1942 by the submarine I-19. Thus, until the return of USS Enterprise in October, only the USS Hornet remained in the battle zone. On 16 October, the aircraft of VF-5 (USS Saratoga), which had initially been sent to Espiritu Santo, were moved to Guadalcanal together with those of VF-71 (which following the sinking of USS Wasp had been stationed on the USS Hornet). Thus, the Cactus Air force, already comprising airmen from the Army and Marines, was joined by pilots of the US Navy.

F4F-4 Wildcat „white 19” BuNo. 03417, pilot Lt. Stanley W. „Swede” Vejtasa, VF-10/USS Enterprise. During the Santa Cruz Battle on 26th October 1942 Vejtasa shot down two dive bombers and five torpedo aeroplanes in one sortie. Artwork by Zbyszek Malicki

The Battle of Santa Cruz

For the next clash of aircraft carriers, the Japanese assembled two attack aircraft carriers and three light carriers. But luckily for the Americans, they divided them into two separate groups. In response, the US Navy could muster only two fleet aircraft carriers – USS Enterprise and USS Hornet. Between 25 and 27 October, these forces traded blows north of the Santa Cruz Islands.

The combatants appeared almost simultaneously, and the waves of enemy aircraft – each heading for their respective targets – passed each other in the air. The fighter escort of the bombers from the aircraft carrier Zuiho (Lieutenant Hidaka) could not resist attacking Air Group Ten from USS Enterprise.

Waves of conventional and torpedo bombers closed in on the opposing aircraft carrier groups. An air patrol from USS Enterprise intercepted the aeroplanes from Shokaku. But the patrol was positioned incorrectly – too low in relation to the oncoming Aichi “Val” dive bombers (armed with 500 kg bombs) – and this made the intervention difficult. Lieutenant Stanley “Swede” Vejtasa shot down two dive bombers from the first wave, and immediately afterwards turned his attention to a somewhat easier target: fifteen Nakajima “Kate” bombers, armed with heavy torpedoes and led by a veteran of Pearl Harbor and the Battle of the Coral Sea, Lieutenant Commander Shigeharu Murata. Five of the aeroplanes fell prey to Vejtasa, and only five actually attacked USS Enterprise. Three were immediately shot down by anti-aircraft artillery fire from USS Enterprise and the battleship USS South Dakota. One crashed into the ocean, while the last managed to correctly launch its torpedo. The aircraft carrier outmanoeuvred it by a whisker – 15 metres, to be exact.

U.S. Navy pilots Lt. Dave Pollock and Lt. Swede Vejtasa of Fighting Squadron 10 (VF-10) “Grim Reapers” aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) off Guadalcanal, in October 1942, shortly before the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. The two pilots have dragged two heavy chairs up to the flight deck to illustrate their boredom. wikipedia.

A U.S. Navy Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat fighter piloted by Ens. Lyman Fulton of Fighting Squadron 10 (VF-10) “Grim Reapers” prepares for launch from the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) before the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, on 24 October 1942. Note the small bright number “17” on the engine cowling (17th plane of VF-10). Note: John B. Lundstrom in The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, page 340, identifies this plane as BuNo 5229. Wikipedia.

The exchange of blows continued, and USS Hornet was eventually lost, while the USS Enterprise suffered damage. Both the Shokaku and Zuiho received hits. The battle was a tactical victory for the Japanese, however gained at the cost of nearly one hundred experienced pilots. The Japanese aircraft carriers withdrew, while the land offensive, which was being conducted simultaneously, ended in failure. After two weeks of repairs at Espiritu Santo, the USS Enterprise returned to battle in early November.

The Climax on Guadalcanal

By the beginning of November 1942, all available forces had been gathered for the decisive fight for Guadalcanal. Since the first days of October, the island was home to a completely new fighter unit – Marine Fighter Attack Squadron VMF-121. Over a month of fighting, it became the most effective Allied combat unit, gaining 165 kills. The commander of its second section, Lieutenant Joe Foss, scored twenty-six kills, thereby equalling Eddie Rickenbacker’s record from the First World War.

P-400 Airacobra „white 13” „Hells Bell”, BW151, 67FS/347FG, pilot Lt. Robert M. Ferguson, Guadalcanal, August-November 1942. See Wolf William, “13th Fighter Command in World War II” p. 58 & 50. Artwork by Zbyszek Malicki.

The USAAF forces were also strengthened. The first Aircobras from 70th Fighter Squadron arrived at the beginning of October; those of 68th Fighter Squadron reached the island in November, and were soon joined by P-38 Lightnings from the 339th Fighter Squadron. All these sub-units were under the operational command of the 67th Fighter Squadron until December. At more or less the same time, individual regiments of the 25th Infantry Division started to arrive on the island, with the second being due to land in the first half of November. The second was due to land in the first half of November. Assorted sub-units of the 2nd Marine Division were also transferred to the front. The only seaworthy aircraft carrier, protected by two battleships, was located to the south-west of the island. Some of its aeroplanes were temporarily moved to Guadalcanal.

The Japanese, convinced that they had sunk two US Navy aircraft carriers at Santa Cruz, were readying themselves for an offensive. The transferral of the 38th Division, whose command and supplies were to arrive in mid-November, was soon under way. The enormous supply convoy was escorted by strong naval battle groups and protected from the side of the ocean by aircraft carriers sailing beyond the reach of the Cactus Air Force (north-east of the island).

F4F-4 Wildcat „black 29”, pilot Lt. Samuel Folsom, VMF-121, Guadalcanal. Piloting this aeroplane Sam Folsom shot down two G4M1 Betty bombers on 12th November 1942. More info about the pilot and his aeroplanes you can find in “the Oldest US Marine Pilot” (click link in picture below). Artowrk by Zbyszek Malicki.

The Naval Battles Near Guadalcanal

Between 12 and 15 November 1942, the enemy fleets fought two night battles which determined the outcome of the campaign.

The fighting began on 11 November, when Japanese aircraft from Rabaul attempted to disrupt the unloading of Allied supplies. Next day in the early afternoon, seventeen Betty bombers escorted by Zero fighters attacked American transport ships in the vicinity of Guadalcanal. They were intercepted by eight Wildcats from VMF-121 and eight Aircobras from the 67th Fighter Squadron. A short time later, these were joined by eight Wildcats from VMF-112. The attack was repelled, while the few bombers that managed to escape were no more than flying scrap. Lieutenant Sam Folsom from VMF-121 claimed two victories.

The battle between Japanese battleships and an American cruiser task force which took place during the night from 12 to 13 November was extremely chaotic and in a sense unresolved until the morning hours. The Americans lost two cruisers and four destroyers, sinking two Japanese destroyers and severely damaging the flagship battleship Hiei. In the morning after the battle, Sam Folsom located the enemy vessel and notified the Cactus Air Force of its position; an attack was soon launched, and the Hiei sank. The CAF’s next objective was the enemy supply convoy – within a few days, seven of the eleven high-speed Japanese fleet transport ships were eliminated, rendering the further provisioning of their forces on Guadalcanal practically impossible. Fresh Japanese battleship groups took part in the night battle from 14 to 15 November. By then, the Americans were on their last reserves – the escorts of the USS Enterprise aircraft carrier group. The radar-equipped battleships USS Washington and USS South Dakota, fighting in impenetrable darkness, managed to repel the enemy. The losses which they suffered in this battle precluded any possibility of a Japanese victory at Guadalcanal.

P-39D-2 Airacobra „white 12” „Beth”, Cpt. Paul Bechtel, 12FS commander, Guadalcanal, December 1942. See Wolf William, “13th Fighter Command in World War II” p 104 & 95-96. Artowrk by Zbyszek Malicki.

Victory at Guadalcanal

In December, the American forces reinforced their position. The newly established 347th Fighter Group took over command of USAAF units from 67th Fighter Squadron. Two additional USAAF units – the 12th and 44th Fighter Squadrons, equipped with the P-39 Aircobra – arrived on the island. This made it possible to press and harry Japanese forces located on other islands of the Solomons, with fighters being sent to bomb advanced enemy positions. However, thanks to the destroyer group of Commander Tanaka (the so-called “Tokyo Express”), the Japanese managed to evacuate their troops by February 1943 in good order.

On 13 January 1943, the Americans established XIII Fighter Command (basing on Thirteenth Air Force), which incorporated the fighter units of Cactus Air Force. Its first task was to secure aerial dominance over the central Solomon Islands. Before spring, successive groups of USAAF P-38 Lightnings and P-40 Warhawks arrived on the island, accompanied by the first Marine Corps Corsair F4U-1s. The last Japanese attempt at stopping the enemy on the Solomon Islands and in New Guinea was the I-Go offensive (1–16 April 1943). This was a series of attacks launched using fresh aviation forces (including crews transferred from aircraft carriers) against Allied airfields and shipping in the area. The Japanese reported shooting down 175 aircraft and sinking several vessels. In fact, they destroyed only twenty-five aeroplanes, losing fifty-five crews in the process. Their biggest loss was that of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto (Commander of the Combined Fleet), who was ambushed and killed in a precisely conducted operation while flying over Bougainville on 18 April 1943. The mission was carried out by Lieutenant Tex Barber, who flew a P-38G Lightning of 339th Fighter Squadron from Guadalcanal.

P-39D-1 Airacobra „yellow 56” 41-38400, 68FS/347FG, Guadalcanal, December 1942. Piloting this aeroplane Lt. Vernon Head of 67FS performed a bombing attack over New Georgia. See Wolf William, “13th Fighter Command in World War II” p. 91. Artwork by Zbyszek Malicki.

F4F-4 Wildcat „white 2”, pilot Mjr. Marion E. Carl, VMF-223, Guadalcanal, February 1943. Artwork by Zbyszek Malicki

Marine Corps Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter at Henderson Field, 2 February 1943. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives.

Catalog #: 80-G-37932

Recommended Reading

- Doll, Thomas. Marine Fighting Squadron One-Twenty-One (VMF-121). Squadron Signal, Carrolton 1996.

- Hammel, Eric; McKelvey Cleaver, Thomas. The Cactus Air Force, Bloomsbury Publishing. Kindle Edition 2022.

- Lundstrom, John B. The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, Naval Fighter Combat from August to November 1942. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis 2005.

- Wolf William, 13th Fighter Command in World War II, Air Combat over Guadalcanal and the Solomons. Shiffer Military History 2004.

Check more:

- Order Cactus Air Force Deluxe Set – F4F-4 Wildcat® and P-400/P-39D Airacobra over Guadalcanal online in the Arma Hobby online store

Modeller happy enough to work in his hobby. Seems to be a quiet Aspie but you were warned. Enjoys talking about modelling, conspiracy theories, Grand Duchy of Lithuania and internet marketing. Co-founder of Arma Hobby. Builds and paints figurines, aeroplane and armour kits, mostly Polish subject and naval aviation.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski