How great must have been the annoyance of the fighter pilots of Nos. 802 and 883 Squadrons in September 1942, who were flying their old Sea Hurricane IBs from the escort carrier HMS Avenger in the desperate defence of the PQ 18 convoy to Murmansk in Arctic waters, while fully aware that Hurricane IICs, with better engines and armed with four 20-millimeter cannon, lay idly in the holds of the freighters they protected? The surviving veteran pilots of the ice-cold route remembered this anxiety for the rest of their lives.

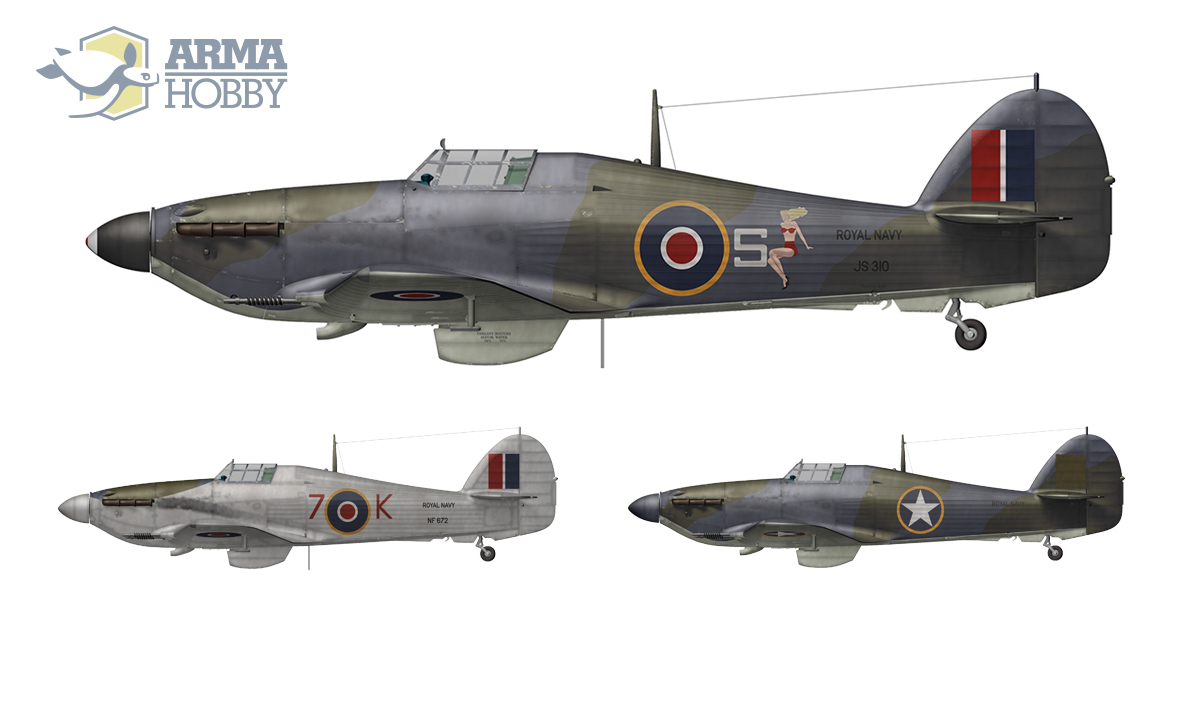

Sea Hurricane IB from No. 802 Naval Air Squadron, HMS Avenger, summer 1942

Navy in need

Substantial deliveries of the Hurricane IICs to first front line squadrons of the RAF commenced in April 1941. Meanwhile, the Fleet Air Arm had only just begun initial operation of the old Mk Is, withdrawn from RAF units and modified for use over the sea. Only 120 of the converted Sea Hurricane Is were available in October 1941. The land-based Mk IIC weighed 7,880 pounds (3,574 kg) and had a top speed of335 mph (540 km/h) at an altitude of 16,600 feet (5,060 m), not an excessive price for a powerful, devastating salvo of four cannon (each with 91 rounds at that time).

Initially, attempts were made to create a hybrid Hurricane for the land-based air force that combined the old Mk I fuselage with the already available new wings with four cannon, but the performance was poor. The naval aviation tried the same thing by combining the fuselage of the Merlin III-powered Sea Hurricane IB and the cannon wings. This was how the first sea Hurricane IC was created. The effect was even worse, because the machine was overloaded not only with weapons, but also with additional naval equipment. As recorded by Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown, the Navy’s legendary test pilot, who conducted trials of the Sea Hurricane IC also during night landings on aircraft carriers, the aeroplane attained 256 knots (474 km/h) at an altitude of 15,000 feet (4,570 m). It was a dead end.

Hurricane Mk IIc – myśliwiec na każdą porę, w nocy i w dzień

Information about the Mk IC participating in combat that can be found in various publications should therefore be treated sceptically. Since 50 to 100 such fighters were ordered, but in January 1942 No. 811 Squadron based at Lee-on-Solent was only partially re-equipped with these, the unit’s main task being to patrol the coast, together with the unwanted Chesapeake bombers (the British name for the American SB2U Vindicators), there could have been only few of them. Some authors claim it all ended with one prototype, V6741. Many authors say, quite reasonably, that the Ministry of Aircraft Production allocated to the Royal Navy 25 or 26 land-based Hurricane IIAs from the initial series (no longer wanted by the RAF because newer ones were already available), each armed with eight machine guns, for conversion into naval fighters. However, in their case, the Sea Hurricane IB designation was still used, eventually. These were the first navalised machines with the Merlin XX engine and, obviously, longer fuselage.

March 1943 – Hawker Hurricane IIC KZ295 in desert camouflage in the final stages of assembly in the hands of girls working at Hawker’s works in Langley. Only a few KZ series Hurricane IICs ended up in the hands of naval pilots. The fighters of this production block no longer received arrestor hooks, but probably navy radio equipment. For example, KZ573 was used in June 1943 to train Fleet Air Arm pilots in No. 787 Squadron in Yeovilton. The trace of KZ295 ends somewhere in the Soviet Arctic… Photo: Adam Jarski collection

Since the RAF already had the new cannon-armed Hurricane IICs in 1941, the Admiralty wanted to be able to order their naval version for their aircraft carriers as soon as possible. The growing demand for the Hurricanes with high firepower (which could also be used for ground attack missions) in the Middle and Far East, but also in Russia, meant that the Fleet Air Arm was far in a long queue. To make matters worse, in 1942 the Americans also needed more and more Wildcats, so the production of Martlets for the British had to wait.

First orders

As early as March 1942, the Admiralty ordered a batch of 70 Sea Hurricane IICs. It was clear from the outset that these would be factory-fresh machines rather than second-hand ones from the land-based users. Hawker Aircraft Ltd prepared a navalised version of the Mk IIC fighter in May 1942, obtained by modifying a production aircraft (BD787) according to the previously accepted Sea Hurricane standards, that is as in the Mk IB. Apart from the arrestor hook, the prototype was fitted with the reinforcements and spools for catapult take-off, the clipped under-fuselage flaps, and the shock absorber aft of the pilot’s seat. This was, however, too much. The Sea Hurricane IICs were intended for operations from large fleet carriers and from smaller escort carriers without the use of catapults. The escort carriers (mostly built in the USA) had a catapult system for American aircraft, which was completely different from the solution adopted in the Royal Navy.

Following the desperate defence of the convoy to Malta, Operation ‘Pedestal’, Admiral Arthur Lymley Lyster, who was responsible for the aerial part of the Royal Navy operations, urgently requested in August 1942, that by 15 September 60 cannon-armed and hooked Sea Hurricane IIC for operations from aircraft carriers were needed, plus an additional 15 Hurricane IIs without hooks for immediate pilot training, the latter by 1 September 1942! In addition, he demanded urgently the navalised Spitfires, known as Seafires. The Admiralty wanted to have the new cannon-armed Sea Hurricanes for their new operation in the Mediterranean waters: the landings in Africa. The industry was pressured, but the Hawker plants were busy making the machine gun-armed Mk IIBs for the Navy and were not able to quickly replace their wings with the cannon-armed ones of the C variant.

The wings of the IIC version with cannons were manufactured separately and delivered for final assembly. Before landing in Africa, the Admiralty managed to arrange 30 sets of wings with cannons for the Sea Hurricane IIB already built with machine guns. The replacement was carried out by the RAF workshops in Henlow. Hence, squadrons with fighters armed both with machine guns and cannons appeared on aircraft carriers covering Operation Torch. Photo: Adam Jarski Collection

Meanwhile, the Admiralty managed to obtain 30 sets of the C wings and insisted on replacing them on fighters that were already completed. The RAF workshops at Henlow dealt with this under pressure, so that as many cannon-armed fighters were available for the action over Africa as possible. They even managed to fit the external fuel tank plumbing systems in the first 24 of these.

Cuts – the simplest solution

To transform a Hurricane I, battered by its combat career with the RAF, often after the hardships of the Battle of Britain, into a carrier-borne Sea Hurricane IB, it had to be subjected to as many as 80 different engineering procedures. The Sea Hurricane IICs were going to come off the assembly lines of many manufacturers as brand new machines, modified only slightly for the naval service with the use of kits produced by General Aircraft company at Hanworth Air Park near London, which had already dealt with the earlier reincarnation of the Hurricane Is. The production Sea Hurricane IICs were to have full standard flaps, a naval radio set (as well as a naval IFF system) and the under-fuselage hook installation. Later, during their service on smaller escort carriers, they were modified in a peculiar way: by sawing off, more or less carefully, the front parts of the main wheel covers. These were constantly bent during landings, when they hit the densely spaced high mounted arrester cables on the decks of the small aircraft carriers, which led to frequent cases of aircraft overturning. That was why a simple and effective solution was found: cutting.

According to ‘Winkle’ Brown’s notes, the Sea Hurricane IIC attained 297 knots (550 km/h) at an altitude of 22,000 feet (6,700 m). It had a maximum take-off weight of 7,800 pounds (3,358 kg) and carried 100 rounds per cannon.

From factories – to decks

New Sea Hurricane II fighters with the more powerful engines were delivered to Fleet Air Arm fighter squadrons by several manufacturers. A batch of 60 Sea Hurricane IICs, with serial numbers in the NF range (from NF668 to 739, including blocks of unused numbers to confuse the enemy) were built by the Hawker plant at Langley (Contract No. 2719).

This Sea Hurricane NF717 was produced at the Hawker factory in Langley in May 1943. Unlike the complex transformation of the Hurricane I into the Sea Hurricane IB, requiring several dozen technical processes, the modification of the emerging Sea Hurricane IIC fighters on the production line was not so labour-intensive. NF717 was delivered to the Royal Navy in May 1943. She served until the summer of 1944 in second-line squadrons: 748 (until the end of 1943) and 761. Photo: Adam Jarski Collection

Sea Hurricane IIAs armed with eight machine guns and Mk IIBs with twelve guns came from the English plants that produced these fighters: Gloster or Austin. But that was not all. New Hurricanes manufactured in Canada by the Canadian Car and Foundry also reached Britain. These were known as the Hurricane X and XI when powered by the Merlin 28 or 29, and the Hurricane XII with the Merlin 29 engines built under licence by Packard factories in the USA. To further confuse the picture, let us say that some of the new fighters may have been built as naval fighters armed with twelve machine guns, and then converted into Sea Hurricane IICs by replacing the wings (there were many such in the production lists in the JS serial number range). Since no exact production and delivery records of Sea Hurricanes are available, the most reliable authors assume that a total of approximately 800 Hurricane and Sea Hurricane aircraft in a variety of versions were in service with the Fleet Air Arm. About 400 of these were the Mk Is.

Various versions of the Seafire (i.e. navalised Spitfire) were already available at the time, as were the increasingly technically advanced naval fighters from the USA, designed as such from the outset and proven in operations in the Pacific. This, naturally, relegated the Sea Hurricane to the second or third line.

Altogether, the Fleet Air Arm was to have several hundred Sea Hurricane IICs and IIBs, including the Canadian-built variants (according to some optimistic publications, about 450). Some claim that at the end of the war 15 Sea Hurricane IIBs and IICs left behind in depots in Algeria after Operation ‘Torch’ joined the re-formed French naval aviation.

First impressions of experienced pilots

Importantly, thanks to the invaluable listings of British naval aircraft, painstakingly collated by the late Ray Sturtivant, it is clear that deliveries of Sea Hurricane IIBs and IICs to Royal Navy’s aircraft depots, prior to distribution to individual squadrons, commenced in early September 1942. At that time, the Navy had approximately 600 Sea Hurricanes of various models. In the autumn of 1942, after convoy battles in the Mediterranean and the Arctic, the Sea Hurricane, now with a more powerful engine, faced another difficult test: protecting the Allied landings in North Africa. In reality, this meant sending into battle every airworthy aircraft aboard all available British aircraft carriers.

Photo of HMS Avenger during Operation Torch – the aircraft carrier at that time only with Sea Hurricane II on board. It was intended to provide fighter cover for the entire fleet. However, it is difficult to determine the versions of the planes gathered on deck in the photo taken from the destroyer passing by. However, you can see that they have British roundels overpainted with American stars. Photo: Imperial War Museum via Adam Jarski

In the autumn of 1942, the new Sea Hurricane IIBs and IICs were used to re-equip the re-formed No. 800 Squadron, which included experienced flyers who had survived Operation ‘Pedestal’, as well as freshly trained pilots. How were the new fighters received by the group of seasoned aces? Let us refer to R.M. Mike Crosley, who had survived the sinking of HMS Eagle on 11 August 1942.

He was very glad to note that No. 800 Squadron had machines with twelve machine guns, and also those with four cannon, but the most important thing was that he now had 300 more horsepower at his disposal than during the previous clashes over the Mediterranean Sea, when he had flown Mk IBs. There was also a two-speed supercharger that changed automatically to higher gear when the maximum engine boost dropped below eight pounds per square inch, at an altitudes of 10,000 feet. The supercharger gear took about 200 horsepower out from the engine, which led to a marked increase in fuel consumption. However, according to Crosley, the engine’s greater power could be felt clearly.

Rolls-Royce Merlin XX during servicing – on the land-based Hurricane II

However, what pleased Crosley and his colleagues most was the battery of 20 mm cannon in the wings. ‘They were what we had been waiting for’, he noted. The cannon had a high rate of fire: 700 rounds per minute. The calibre allowed it to deliver a lethal blow from a distance of 400 metres. Three types of shells could be loaded: ball, armour-piercing and incendiary-explosive. The muzzle velocity was 2,000 feet per second, which meant they raced towards the target at almost twice the speed of sound.

20mm cannons of the land-based Hurricane IIc. Early variant of the recoil springs visible

Crosley and his squadron colleague, ‘Greyhound’ Thompson, managed to climb in their Sea Hurricane IICs to an altitude of 35,000 feet and, being experienced pilots, they managed to stay there at an indicated speed of just 85 knots! With two 45-gallon tanks under the wings of the Mk IIC, they could fly almost 700 miles in one go, or the distance between the bases at Lee-on-Solent (near Portsmouth in Southern England) and Hatston (in the Orkney Islands, North of Scotland): the whole of Great Britain from down south to far north. This was very useful for the Royal Navy squadrons, constantly redeployed in accordance with the tasks of the aircraft carriers.

Text translation: Wojtek Matusiak

The Sea Hurricane IB’s 90 minutes of operational range after taking off from an aircraft carrier limited its capabilities. In 1942, the Royal Navy, not yet having a Hurricane II with a new wing adapted to carry auxiliary tanks, conducted experiments with suspending them under a catapult-launched Sea Hurricane IB Z7082. Unfortunately, during the tests on January 26, 1943, RAF Corporal Hancock died after being hit by an aeroplane propeller. After testing, the aircraft underwent overhaul at the Royal Naval Air Maintenance & Repair Yards in Fleetlands in Gosport, Hampshire. Then in April 1943, it was assigned to the 800th Squadron. However, the unit was already flying the Sea Hurricane IIC so the veteran plane was sent to training units. Photo: Imperial War Museum via Adam Jarski

Buy 1/72 Sea Hurricane IIc online at the Armahobby.com!

See also:

Currently Defense Analyst. Journalist with more than 30 years of experience in defence reporting from fields of conflicts (Afghanistan, Balkans). Known from TV live commentaries on different contemporary defense and security issues. With catapult launches and arresting landings on the board of USS Saratoga and flights in the rear cockpit of F/A-18 D Hornet in his log book. Devoted scale modeller and great fan of naval aviation.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski