”…Hurricanes! Scramble the Hurricanes!” The fitters in the cockpits pressed the starter-buttons, and the four Merlins opened up with a blast of sound and a gust of blue smoke. As we scrambled up the wings, the crews hopped out the other side, fixing our straps with urgent fingers. Connect R.T.; switch on. Ten degrees of flap. Trim. Quick cockpit check. The ship was under full helm, racing up into wind — and we were off and climbing at full boost on a northerly vector to 20,000 feet, heads swivelling.

Photo: Imperial War Museum, still from film: IWM UKY 425

Down to 12,000; alter course; climb to 20,000 again. And there they were, a big formation of 88’ s below us. One after another we peeled off and went down after them. They broke formation as they saw us coming, and Brian and I picked one and went after him. He turned and dived away, and we stuffed the nose down, full bore, willing our aircraft to make up on him. At extreme range we gave him a long burst; bits came off and smoke poured out of one engine, and then he vanished into the thickening twilight. We hadn’t a hope of catching him and making sure; already he had led us away from the convoy; and so, cursing our lack of speed, we re-formed, joined up with Steve and Paddy, the other members of the flight, and started to climb back to base.

Passion, stubbornness and determination of the young people who, in August 1942, in the Mediterranean, struggled with the moderate speed, the Achilles heel of the Sea Hurricane IB, their ageing mount that was still needed. And, despite their bravery, the poor effectiveness of fire of the octet of machine guns in their kites. All of that can be found in the account of the combat fought by pilots of No. 880 Squadron of the Fleet Air Arm (FAA), embarked on the aircraft carrier HMS ‘Indomitable’, as written down by Hugh Popham, at the time a lieutenant of the RNVR (Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve), in his book ‘Sea Flight’ (first published in 1954). A truly extraordinary author, Popham was an outstanding British poet and novelist, winner of literary prizes. In 1940, he abandoned his law studies at Cambridge to become one of the Riders of the Storm, as he used to say, referring to his own poems and to the official name of his first naval fighter (because the hurricane is also a kind of storm!). It is worth noting that one of his prize-winning poems from a collection published in 1944 was titled Against the Lightning – a Poem from an Aircraft Carrier.

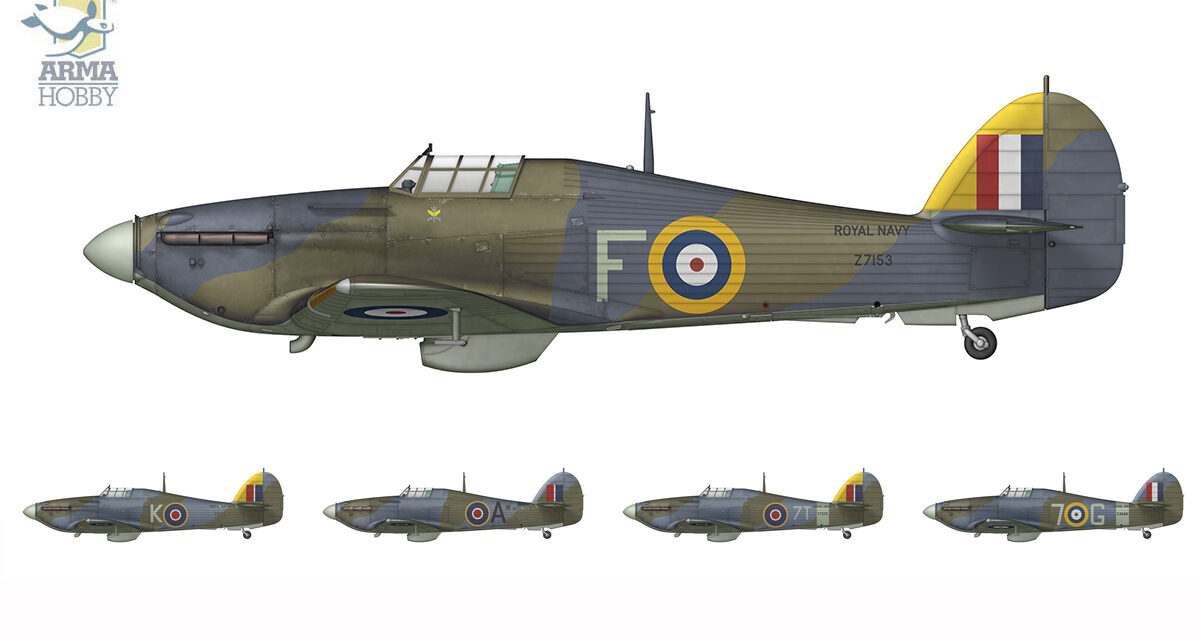

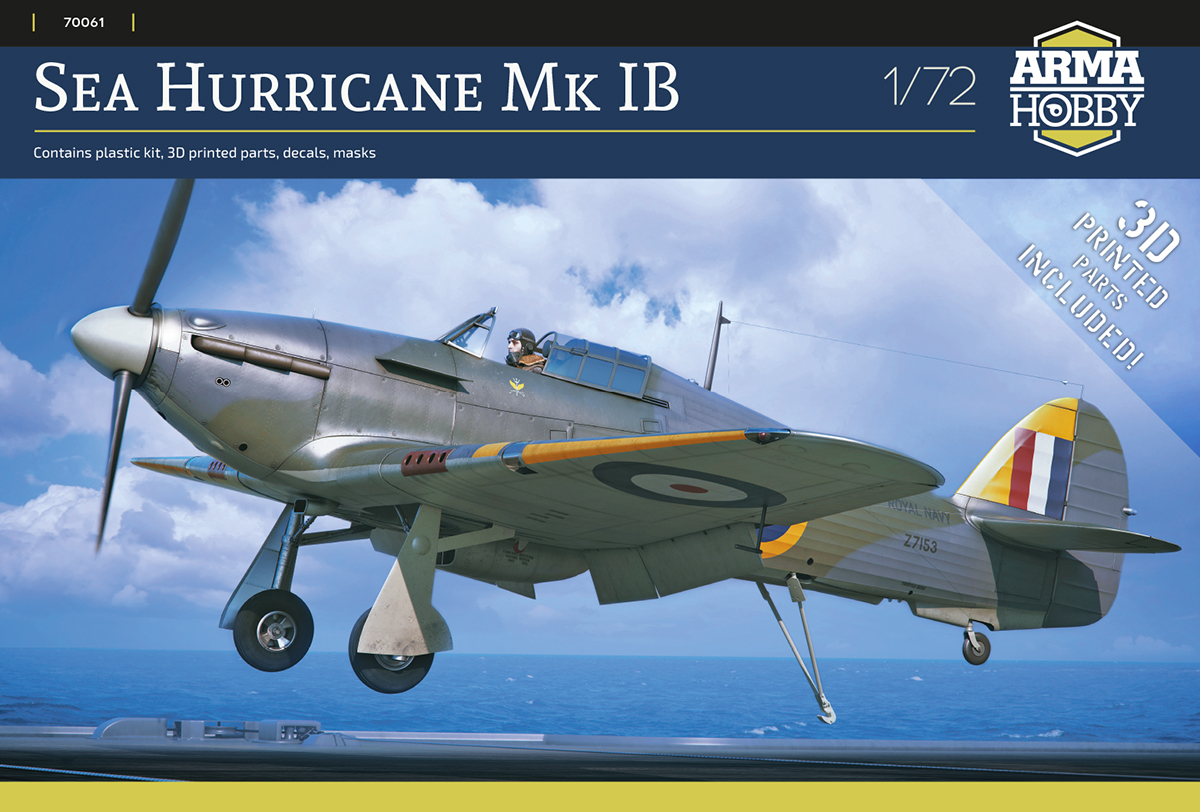

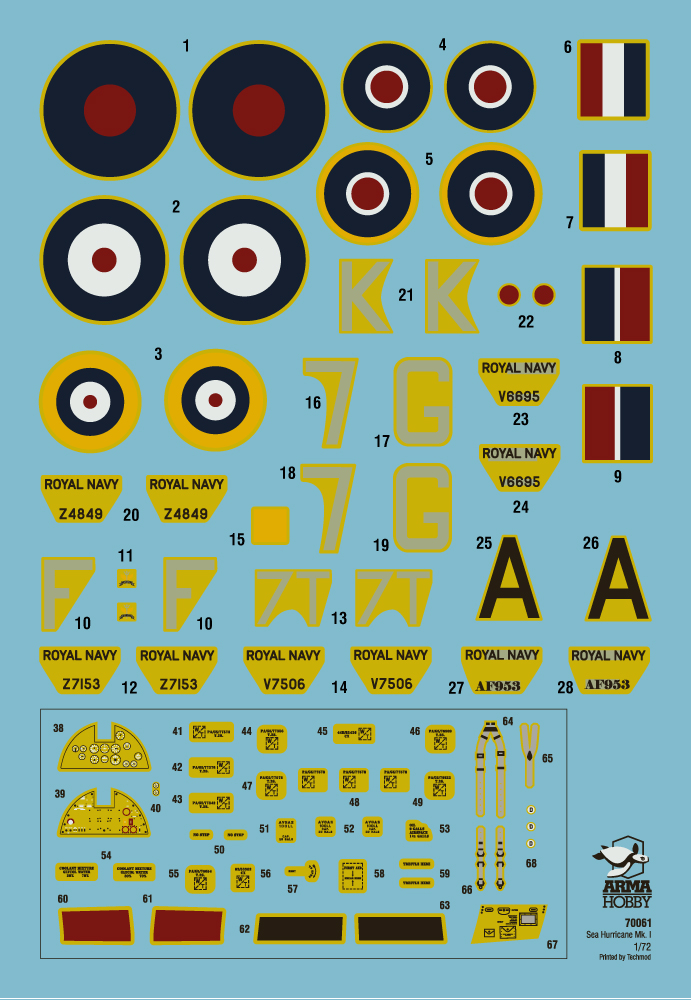

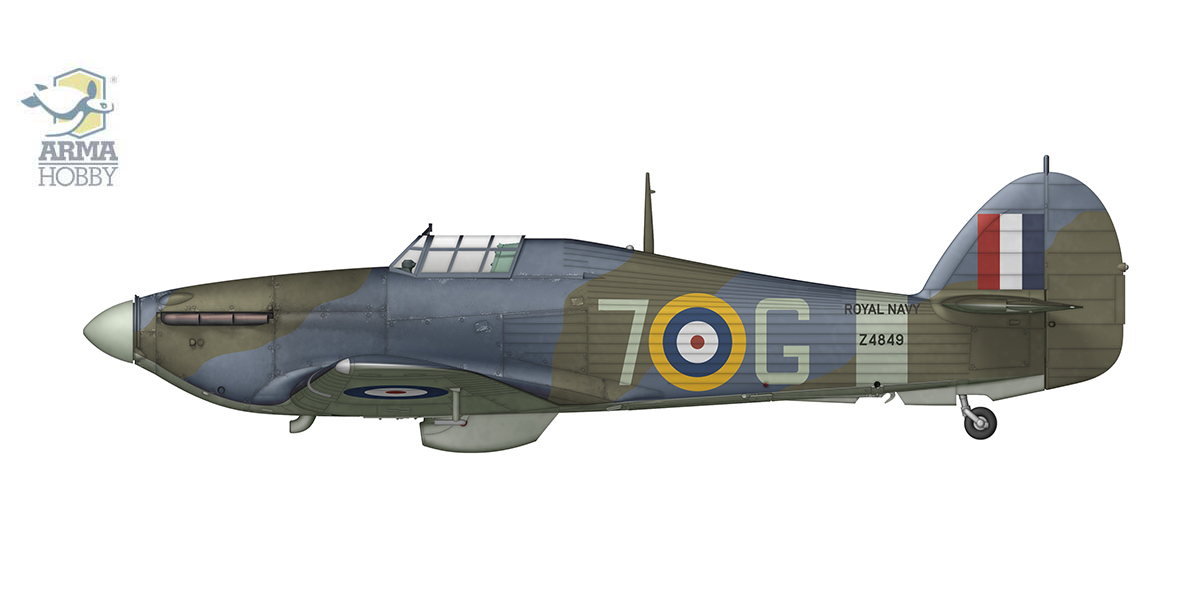

Sea Hurricane IB, Z4849 “7G”, pilot: Sub/Lt Hugh Popham, No. 880 Naval Air Squadron, Operation Pedestal, aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable, August 1942

Sea Hurricane IB, Z4849 “7G”, pilot: Sub/Lt Hugh Popham, No. 880 Naval Air Squadron, Operation Pedestal, aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable, August 1942

Hugh Popham, essentially a civilian to the core, a sensitive and wealthy English gentleman, a volunteer in the uniform of a naval aviator, and his aircraft that entered a decisive clash once more, two years after its greatest glory in the Battle of Britain, both in a way symbolise the FAA’s largest convoy battle. It went down in history as Operation ‘Pedestal’. And the navalised variant of the famous Hawker Hurricane I, desperately adapted for carrier service, became (not a trace of exaggeration here!) the saviour fighter for the Royal Navy’s air arm, a force fighting with its back against the wall during the two difficult years of 1941–1942. However, before we venture into the Mediterranean in the summer of 1942, we need to go back in time a bit, to follow the Sea Hurricane story…

No need to hide it: the Fleet Air Arm of the interwar period, whose floating airfields were built by the navy, the staff was trained by the land-based air force, and the aeroplanes were designed by the Air Ministry, entered the war in a poor condition. Nearly all carrier-based combat squadrons (their number plates in the 800 range, so as not to irritate the RAF with number games!) were equipped with Swordfish biplane torpedo-bombers deployed on seven aircraft carriers. There were only two operational fighter squadrons: Nos. 800 and 803, both on the newly commissioned, state of the art HMS ‘Ark Royal’. Each of these was equipped with the not too successful Blackburn designs: nine conventional Skua fighter-bombers and three Roc turret fighters.

Blackburn Roc, Blackburn Skua, Gloster Sea Gladiator. Photo: Author’s collection

This tiny form of naval aviation was due to the ultra-conservative doctrine, according to which the role of the Swordfish would be to immobilize enemy ships with the torpedoes or bombs during old fashioned great sea battles, leaving the rest to the artillery of the battleships and battlecruisers, still expected to dominate the seas. The role of the carrier fighters was to drive away enemy long-range patrol aircraft in high seas, because any land-based enemy fighters that would dare to venture over the waters were to be dealt with by the RAF.

Such a short-sighted approach, plus the chronic lack of funds for the development of the naval aviation, brought about a real crisis that made itself felt in the first year of the war. It was not solved by the biplane Gladiators, hastily adapted to operate from aircraft carriers, nor by the more modern Fulmar monoplanes, because work on the latter dragged on into the next year.

Cross’ Idea

Squadron Leader Kenneth B. B. Cross, the commander of No. 46 Squadron RAF, is considered the originator of the idea to navalise the Hurricane. The British pilots who, in June 1940, received a signal to retreat from Norway where they had been fighting the attacking Germans since April, faced a tough alternative: burn their aeroplanes or ‘somehow’ make it back to Britain.

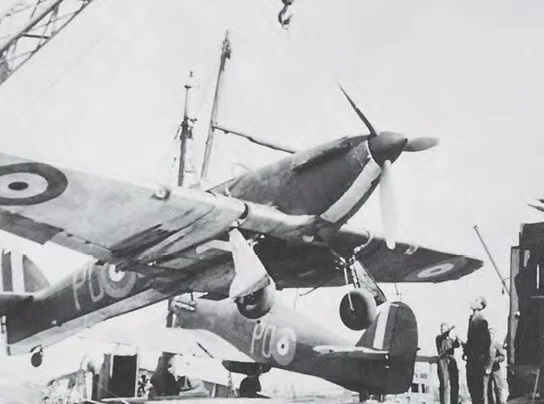

Early May 1940, Greenock. Two of 18 Hurricanes Mk I from No. 46 RAF Squadron winched on board HMS Glorious before departure to Norway. Photo: Author’s collection

The ‘somehow’ for No. 46 Squadron Hurricanes and No. 263’s Gladiators meant one thing: evacuation on the aircraft carrier HMS ‘Glorious’. There was no way the aeroplanes could be loaded onto the deck at a harbour. The only option available was to land on the carrier while at sea. But how to do it in a fighter without an arrestor hook? Cross was already a very experienced pilot, a former instructor, and he calculated everything well. He ordered his aeroplane’s tyre pressure to be drastically reduced, and agreed with the carrier captain that the ship would be steaming at least 26 knots against a wind of at least 15 knots. It was estimated that in such conditions the fighter must come in to land on the deck while maintaining a speed of at least 70 knots and make a precise three point touchdown. Cross successfully alighted his Hurricane on ‘Glorious’ in the evening of 7 June. By 1:15 a.m. on the 8th, the seven remaining aircraft of his squadron landed successfully on the carrier. It was noted that in numerous cases the touchdown speed relative to the deck was no more than 25 knots! The pilots of ten Gladiator biplanes also completed the task without a snag.

Unfortunately, a few hours after the series of safe landings, tragedy struck: ‘Glorious’ and two escorting destroyers were intercepted by the German battleships ‘Scharnhorst’ and ‘Gneisenau’. According to Cross’s account, one of the battleships’ first salvoes destroyed the flight deck and hit the bridge, badly wounding the carrier’s captain. Cross fought for his life in the icy water, and then struggled to survive for three days and three nights on a storm-tossed life raft. He was miraculously saved by the crew of a Norwegian trawler. Only three officers and 41 petty officers/NCOs survived the destruction of the three Royal Navy ships.

Cross eventually rose to the rank of air marshal. He died in June 2003, almost on the anniversary of the sinking of ‘Glorious’.

A meeting at the Air Council Room

Even before the Norwegian campaign, the Fleet Air Arm had requested a number of Hurricane and Spitfire fighters with the intention to navalise these. Advanced designs of these aeroplanes with folding wings or as floatplanes were even prepared in the spring of 1940, for a possible use on the then principal Norwegian front. However, the First Lord of the Admiralty a the time, Winston Churchill himself, rejected these concepts in late March 1940. The idea was revived in the autumn of 1940, when the Battle of Britain had been won, and a new front in the struggle for Albion’s survival had been opened: the Battle of the Atlantic. On 12 November 1940, a top-level meeting was held at the Air Council Room in King Charles Street in London, in a desperate search for an antidote to the scourge of increasingly successful attacks by the four-engined long-range Fw 200 Condor aircraft operating from France against the Atlantic convoys, the solitary Kingdom’s lifeline. It was agreed that the long-range Beaufighters operating from Ireland must be directed by special advanced radar-equipped ships escorting convoys in the middle of the Atlantic. Additionally, it was suggested that such ships should be equipped with catapults to launch two or three fighters, ready to intercept the attackers.

The idea was picked up by Captain Matthew S. Slattery, the Director of Air Materiel Department of the Admiralty, who developed it into two variants.

The first one was to fit catapults for the fighters on merchant ships and the second one was to fit bigger freighters with decks of the simplest design, to enable both take-off and landing of aircraft. Both these solutions were accepted. The former resulted in the construction of the CAM: Catapult Aircraft Merchantmen, and the latter in the MAC: Merchant Aircraft Carriers.

The Navy was tasked to find suitable ships and the Air Ministry was to allocated sixty Hurricane Is, already worn out by RAF squadrons, to modify these for catapult launching and naval operations. This was the beginning of the Hurricat: the expendable navalised Hurricane I, catapult-launched in the middle of the Atlantic, subsequently renamed the Sea Hurricane IA. At the same time, in December 1940, work began on the Sea Hurricane IB, developed for landing on one type of aircraft carrier or another, so definitely less expendable FAA fighters. As fate would have it, the Mk IA would be flown be pilots from RAF squadrons who volunteered for this type of service, as well as those from No. 804 Squadron FAA ordered for it, while the Mk IB would only be manned by fighter pilots of the Royal Navy and officers of the Royal Marines. The stories of these two Sea Hurricane variants, the Mk IA and IB, were therefore parallel. And it must be remembered that unmodified land-based Hurricanes taken over by the Navy were used for conversion training of naval pilots onto the new fighter. These were referred to as the Sea Hurricane I (the same designation was also used for the tropicalised Hurricanes used by land-based FAA units operating in North Africa).

An elderly gentleman on a catapult

Things are usually only easy in theory. Similar take-off weights of the Hurricane and of the standard Royal Navy patrol aircraft, the Walrus amphibian, suggested fitting of the CAM ships with the standard Navy catapult powered by cordite-filled explosive charges. But these devices were few, and they only accelerated the aircraft to 60 mph (95 km/h), while the Hurricane needed at least 80 mph (125 km/h) to take off. Churchill requested many hundreds of CAMs at first, then reduced the number to 250. The Royal Navy suggested 50. Eventually, 35 were prepared. Engineers at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, designed the simplest catapult possible, with rail lenght of 75 feet/23 m (another version had 70 feet/21.3 m), which accelerated the trolley with standard naval aircraft attachments using the energy of thirteen electrically fired three-inch (76.2 mm) take-off rocket boosters.

Because the pilot’s body was subjected to a 3.5 g overload, a special drill was prepared for the take-off actions: full throttle – ready signal for the staff member who launched the rocket battery – left hand off the throttle lever and up, right foot one third starboard rudder, flaps one third down, trim tabs in neutral, right elbow jammed into the right hip to prevent an instinctive pulling of the stick caused by the rapid acceleration. To prevent head injuries, all Sea Hurricane IAs and IBs were fitted with an additional round padded head rest on the frame in front of the armour plate.

The Sea Hurricane IA and IB airframes had been through a lot when operated by RAF squadrons. In some cases they were very, very worn out before being refurbished and fitted with catapult attachments. The attachments mounted on both sides of the radiator were in the form of rollers. Fitting these required shortening the flaps in order that the aircraft was able to leave the catapult trolley structure smoothly. All this required strengthening the fuselage trusswork and, in the case of Sea Hurricane IBs that would operate from aircraft carriers, installing an arrester hook to catch the cables on the aircraft carrier deck. A special green light in the cockpit informed the pilot about the hook release. Naval radio and the Navy IFF radar identification system (its aerial extending between the ends of the tailplane and the fuselage) were also installed.

The catapult training of MSFU (Merchant Ship Fighter Unit) pilots, assembled at the old Speke airfield near Liverpool (a copy of the ship catapult was installed there on 6 June 1941) was headed by an excellent pilot, Squadron Leader Louis Strange, aged 49 at the time. He was a World War I ace, he had escaped bravely in an unarmed Hurricane from France in 1940 under the noses of the advancing Germans, and had then commanded the parachute training centre at Ringway. He was the first to get catapulted using the rockets. Following a perfect take-off, he announced to his subordinates: If an old boy like me can do it, it won’t mean a thing to lads like you…

Apart from the pilots, each CAM had to have additional deck crew for the aircraft: two mechanics, a radio operator, and an aircraft armourer. The Royal Navy also delegated their own radar operator, a torpedo operator to man the catapult from a special armoured cabin, and the most important person: the FDO or Fighter Direction Officer, responsible for guiding the pilot onto the target and bringing him back over the convoy. The rest of the CAM staff were civilians from the merchant navy. In theory, the decision to launch the Sea Hurricane IA was taken either by the escort commander or the commodore of the convoy, while the actual moment of launch was decided by the FDO. Ultimately, however, it was the pilot who had to decide whether the weather conditions were suitable. In reality, it varied. What is important is that during the preliminary catapult trials at Farnborough (mainly using Fulmar fighters) no accident was recorded in 60 launches. But no one could tell what it would look like on a ship and at sea.

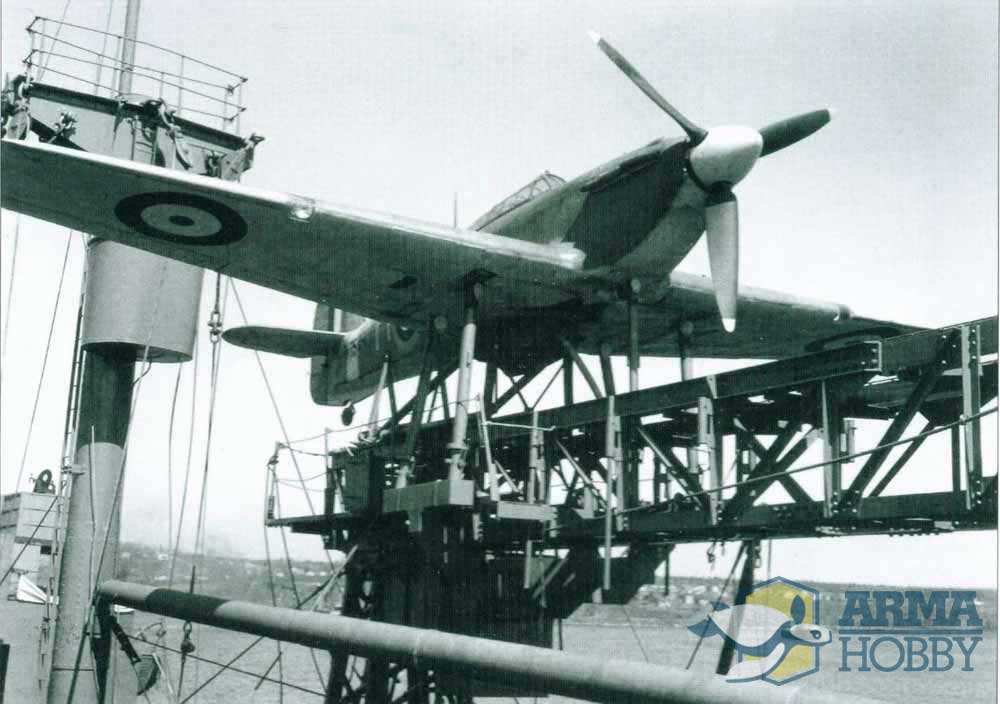

Sea Hurricane Mk Ia, V7504, on CAM ship’s catapult ready to be launched, if or when the necessity arose, in 1941. Photo: Tony O’Toole collection

Pilot Officer H.J. Davidson was the first to go through a trial launch from the catapult on SS ‘Empire Rainbow’, the ship sailing at 10 knots into a 2 knot wind. A tragedy was narrowly escaped. The fighter brushed the sea with the port wing and the pilot struggled desperately to get airborne, eventuall succeeding. It turned out that he forgot to lower the flaps in his emotions, he throttle lever returned automatically to the 50% position at the point of take-off (later it was recommended to strengthen its clamps), and the cover of the rocket booster stowage blew off, damaging the tail wheel. Somehow, however, he managed to land at Abbotsinch.

Navy Lieutenant Robert W. H. Everett, aged 40, an outstanding jockey before the war, then a pilot of No. 804 Squadron FAA, went down in history. On 18 July 1941, he was catapulted from CAM ‘Maplin’ (painted in civilian strawberry pink for camouflage, the holds filled with empty barrels to ensure buoyancy in the event of a torpedo hit). The Condor against which he was scrambled was shot down by fire from ‘Norman Prince’, however. The pilot decided to fly to the shore of Ireland, covering over 300 miles. On 3 August 1941, he was catapulted again from CAM ‘Maplin’. This time, following an exhausting pursuit, the Sea Hurricane IA caught up with a Condor for the first time, dispatching it into the sea. Everett was also hit by return fire from the gunners, his engine losing oil. Somehow, he managed to fly more than 40 miles to get back to the convoy. After two attempts to bale out, the pilot decided to ditch. He almost drowned. Sadly, Bob Everett, a DSO-decorated and feted hero, was lost with Sea Hurricane IA P3452 off the isle of Anglesey during a routine flight on 26 January 1942…

Eight CAM ships were requisitioned from private owners (two subsequently sank). 27 more CAMs belonged to the Crown (ten sank). Eight Sea Hurricane IAs were catapulted in combat conditions. Only one pilot, John Kendall, aged 21, was killed in action: he defended the PQ 16 convoy to Murmansk, shooting down a Ju 88 (after baling out he was picked up from the sea and resuscitated, but unsuccessfully). He was a Battle of Britain veteran, having flown Spitfires with 616 Squadron, credited with two Bf 109s destroyed.

A total of six enemy aircraft were claimed destroyed (according to some sources, only three or four Condors). The last two ‘kills’ were credited to Flying Officers Patrick Flynn and John Stewart. The Condors crashed into the sea on 28 July 1943, over 800 miles west of Bordeaux.

What the Sea Hurrie IB was like

The conversion of several dozen aircraft into the expendable Sea Hurricane IA catapult fighters was done by General Aircraft Ltd at Hanworth Air Park near Feltham, south-west of London. There was nothing unusual about it, as the company already had experience with Sidney Camm’s designs. For example, since 1936, they had licence-built the Hawker Fury II biplane fighter (the forerunner of the Hurricane!). It is an interesting detail that the Mk IAs were fitted with additional 44 gallon fuel tanks, which gave them a slightly longer range and the ability for the pilot to return to a shore base. It is another interesting fact that as a result of the operations of the CAM units and their Hurricats, later in the war several dozen of those converted fighters were left behind in sea ports on both sides of the Atlantic. In Canada, for example, these were used for pilot training.

Photo: Imperial War Museum/Adam Jarski Collection via Autor

Some 300 Hurricane Is, all badly worn and some worn out too much (their lamentable technical condition was discussed in complaint letters from the Admiralty!), were initially transferred (very reluctantly!) from RAF stocks for conversion to Sea Hurricane IB naval fighters, which involved fitting arrester hooks and catapult attachments, at General Aircraft Ltd. In March 1941, the first hooked Hurrie was assembled and transferred for testing to RAE Farnborough. As usual with the FAA, it was needed at once, so modify the wing with a folding mechanism was impossible. This affected seriously its service aboard Royal Navy aircraft carriers. Older ships were able to fit the Hurricanes on their large hangar lifts. Others, such as HMS ‘Victorious’, HMS ‘Illustrious’ or HMS ‘Formidable’, had to store them on the flight deck (where only six could be accommodated), sometimes with the tails extending overboard and the tail wheel on a special outrigger. The first hooked Sea Hurrie IBs were ready in April 1941.

Needless to say, vis-à-vis the best shore-based fighters of the period, these aircraft were already obsolete. The Sea Hurrie IB was powered by a 1,000-horsepower R-R Merlin III, which could drive various propellers. The FAA pilots seconded to the RAF in the Battle of Britain had flown Hurricanes with the more efficient three-bladed wooden, constant-speed Rotol propellers. The Navy, however, chose an older metal de Havilland two-pitch propeller for its Mk IBs. Its lower weight was the reason: it was found out during carrier landing tests that the aircraft appeared nose-heavy when subjected to rudder corrections in the last phase of the approach. When flown by less experienced pilots, this could result in the propeller blades hitting the deck. That was why the lighter de Havilland variety was chosen, even if this affected the overall performance.

Photo: Imperial War Museum/Adam Jarski Collection via Autor

During the Battle of Britain, Robert Michael Mike Crosley, later an FAA ace and Navy Captain, was a police officer dreaming of becoming a pilot. In the summer of 1941 he was already training at Yeovilton. First on the shore-based Hurricanes I provided for the Royal Navy and then on Sea Hurricane IBs. The former had seen much better days: oil was leaking by gallon and soiling the windshield, spark plugs were always oiled-up, coolant leaks were commonplace, brakes barely worked, and many of the aeroplanes still had the oldest, fabric-covered wings… Crosley remembered that in the summer of 1941 there were still very, very few hooked Hurricanes, and the first attempt to land on HMS ‘Argus’ that was used for exercises was completed successfully by a pilot named Bromwich, in whose opinion it was easy. For the FAA pilots, even these horribly worn-out trainer fighters were a fantastic ticket to the modernity. The twelve pilots of Crosley’s 4-month course were fascinated. My first take-off in a Hurricane was like a first ride on a high-powered speed boat, noisy, shaky and out of control, and with the same colossal acceleration which almost dragged my hand off the throttle and jerked my head back against the headrest, it was so unexpected…, he recalled. It was so much different from flying the Fairey Battle bomber that Crosley and his colleagues had mastered, as originally they were being prepared to pilot the Fulmars that behaved similarly.

Short in range with the ditching propensities of a submarine, harsh stalling characteristics, a very mediocre view for deck landing and an undercarriage that was as likely as not to bounce it over the arrester wires. What less likely a candidate for deployment aboard aircraft carriers as a naval single-seat fighter than the Hurricane could have been imagined… Yet, the Hurricane was to take to the nautical environment extraordinarily well. This was the opinion of a Fleet Air Arm legend, Captain Eric Winkle Brown, a Royal Navy test pilot (over 1,500 touchdowns on 22 ship types, including the world’s first on a Sea Vampire jet). When Brown noted down his observations, he knew exactly what he was saying. He had already ditched spectacularly no less than twice in the cockpit of the American Grumman Martlets (later known as Wildcats). The second of these incidents took place in May 1941 in the Firth of Forth in front of Churchill himself!

Sea Hurricane 7U of No. 855 FAA Squadron on HMS Victorious board, and, with folded wings, Fulmar Mk II 6P X8364 of No. 809 FAA Squadron. In the background: HMS Indomitable with Sea Hurricanes, HMS Eagle and HMS Argus Photo: Imperial War Museum/Adam Jarski Collection via Author

As fate would have it, the Sea Hurrie IBs served alongside the Fulmars during the most difficult period of the war in the Mediterranean, and then in the northern waters. It quickly turned out that the aircraft, laden with naval additions, with an older propeller, was slower by no less than 40 mph (64 km/h) than its shore-based counterpart. It took 6.2 minutes to climb to an average operating altitude of 10,000 feet (a standard Hurrie did that in 4.1 minutes). Soon, comparisons were made between the Fulmar and the stop-gap Sea Hurrie IB. The new FAA fighters, or the old RAF ones, were — in the words of former FAA aviator David Brown — barely capable of 300 mph at 18,000 feet, and although they had the same armament as the Fulmars, they had only half the ammunition capacity and less than half the patrol endurance. Comparative trials of the Sea Hurrie IB and the newer Fulmar II, which fought together in Operation ‘Pedestal’, showed that the smaller single-seater was inferior below 10,000 feet. This was taken into consideration in 1942, when higher protection of the ships was assigned to the Sea Hurricanes, and the lower one to the Fulmars.

Let us get back to Captain Eric Brown (in 1941 a Navy Lieutenant with two downed Condors to his credit, while flying the American Martlets). After the loss of HMS ‘Audacity’, the Royal Navy’s first escort carrier, in December 1941 (from which Winkle Brown had flown Martlets to fight the Condors), he was posted to No. 802 Squadron. Together with No. 833 Squadron, these were to be the first Sea Hurrie units to operate from the a small escort aircraft carrier, HMS ‘Avenger’. On 1 February 1942, Brown reported at RNAS Yeovilton, where he was given the post of No. 802 Squadron Armament Officer. In May 1942, Brown tested the Sea Hurrie IB in action from HMS ‘Avenger’, a carrier that would go down in the history of this fighter. As he said himself, the excitement he had felt for the first time while flying a land-based Hurricane I in the autumn of 1940, has returned at the controls of the new naval fighter. His observations were as follows.

Winkle Brown’s account

In his opinion, the Martlet/Wildcat was superior to the Sea Hurricane IB in almost every aspect, because it was a ‘natural born’ naval fighter, while the British aircraft was merely a modification. Unfortunately for the Royal Navy, they could not expect continuous large deliveries of the Martlets/Wildcats. The Grumman fighter was much better, also in terms of the armament, except for one thing: the American aeroplane was very stable and inferior in dog fight to the more manoeuvrable Sea Hurricane. But the latter was no match whatsoever to the American type in terms of the range.

In flight, the Sea Hurrie was stable about all three axes. In a dive it became tail heavy. But one had to remember not to correct that with the trim tabs, because this would lead to serious difficulties during recovery. The Sea Hurricane’s flying stability increased with speed. It achieved neutral control at 139 knots (258 km/h). Stalling speed was 68 knots (126 km/h) with the undercarriage and flaps up, and 57 knots (106 km/h) with the undercarriage and flaps down. In such conditions, the machine became longitudinally unstable, which forecasted a rapid drop of the wing to the vertical and a spin, which had to be avoided at this stage. Deliberate spinning was strictly prohibited. And if it happened in the heat of a combat, in a tightening turn at low speeds, one had to keep in mind that normal recovery from the spin was possible, but it was associated with… a significant loss of altitude.

Aerobatics in the Sea Hurrie IB were easy and pleasant, provided a margin of speed was kept. Comfortable loops required an entry speed of around 260 knots (482 km/h), although they could be performed at lower speeds. Rolls could be made already at 156 knots (290 km/h). In general, it was a very manoeuvrable aircraft with a good harmony of control throughout the speed range. Controlling the ailerons required the least force, the rudder bar was the heaviest in manoeuvres. As the speed rose, the forces required to deflect the control surfaces rose, too. Still, the controls remained effective up to the top speed. The landing flaps could be deflected smoothly to any position, depending on the situation. This increased manoeuvrability in combat. However, they did not lower immediately. They took 8–10 seconds to get fully down. If they were set in the fully down position in combat, then above 104 knots (193 km/h) they would partially retract due to the increasing airflow drag.

During the landing approach, the cockpit hood was slid back at 120 knots (222 km/h), the landing gear was extended, the trimmers set to neutral, and the propeller pitch to the fine position. The flaps had to be lowered below 104 knots (193 km/h), which allowed the approach speed to be maintained at 78 knots (145 km/h). When landing at a shore base, forward visibility was reasonable and a three-point touchdown was fairly easy. When landing on an aircraft carrier, it was possible to reduce the speed to 70 knots (130 km/h). The Sea Hurricane did not provide good sight of the deck during this, and it was impossible to make a crabbed approach using the feet on the rudder bar, as was later developed in the cockpits of the Seafires, the navalised Spitfires. Deflecting the large rudder of the Sea Hurricane when landing at low speeds made the aeroplane suddenly nose heavy, which could end badly at this very delicate stage of flight. Ultimately, the poor forward visibility and the straight approach to touchdown on the deck had to be accepted for lack of a better option. The pilot had to have it in the back of his head that the speed had to be maintained as losing it would entail the fatal consequences of stalling. And also that the design of the chassis virtually encouraged bouncing back on touchdown. Fortunately, it was robust and wide, and thus able to withstand this. Quite unlike that of the Seafire.

Eric Brown’s opinion was clear: the characteristics of the navalised Hurricanes were far from what should be expected from an ideal carrier-based fighter. However, as it turned out, the Sea Hurricanes had to defend British naval groups not only from large Royal Navy aircraft carriers, but also from improvised smaller escort carriers. As fate would have it, after the great convoy battles of 1942, the aircraft continued to be used from the latter ship almost until the end of the war, even though better naval fighters from the USA had become available.

Text translation: Wojtek Matusiak

Check also:

- Buy Sea Hurricane Mk.Ib and other model kits online in the ArmaHobby.com shop!

Currently Defense Analyst. Journalist with more than 30 years of experience in defence reporting from fields of conflicts (Afghanistan, Balkans). Known from TV live commentaries on different contemporary defense and security issues. With catapult launches and arresting landings on the board of USS Saratoga and flights in the rear cockpit of F/A-18 D Hornet in his log book. Devoted scale modeller and great fan of naval aviation.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski