From Editor: in the first part of the article, Grzegorz Cieliszak described the genesis of the “Flying Tin Opener” – Hurricane Mk IID, armed with 40 mm anti-tank cannons. The second episode presents combat operations over Africa, to which No. 6 Squadron RAF entered after intensive training in the spring of 1942 in Egypt.

In action over the Western Desert sands

Just as had been planned, the unit was declared ready for combat operations following a month of instruction, and on 5 June 1942 nine aircraft from flights A and C flew to Gambut airfield near the Western Desert front line, which was moving forward rapidly. The Battle of Gazala had been raging for several days, and Rommel’s excellently commanded armoured units had broken through the Allied defences. The first operational flight took place on 7 June and was intended to support the 1st Free French Division of General Marie-Pierre Kœnig, which was defending Fort Bir Hakeim. However, the aircraft did not find their targets and it was not until the next day – in the very same area – that their baptism of fire took place, when a section of three Hurricanes found the enemy and Wing Commander Roger Porteous, commander of the squadron, flying on BN841, reported hitting a tank and a truck.

Hurricane IID attacks a ground target. Still from the Imperial War Museum film, used under the right to quote

His wingmen added one more tank and two trucks. The commander returned home, however his aeroplane was damaged by flak. The second section took off in the same area in the early afternoon and reported destroying three tanks and two trucks, but this time the enemy put up an even stouter defence and two Hurricanes were shot down. The pilot of BN861, Canadian Flight Lieutenant Allan James Simpson, was hit by anti-aircraft fire and a flak and wounded by a splinter in the chest and right arm. Nevertheless, he pressed home his attack and successfully attacked two tanks and a truck. Hit yet again by flak and scalded with hot oil – and also blinded by smoke – he managed to rise to a height of approximately 500 feet and escape from the now burning aircraft on a parachute. In recognition of his bravery and dedication, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. The pilot of the second Hurricane to be hit, BN860, Flying Officer Anthony Eustace Morisson-Bell, returned to the unit the next day without suffering any injury.

Allan James Simpson’s action described by “The London Gazette” from 11 August 1942

The operational début of the Hurricane IID was duly noted by the defenders of Bir Hakeim, who on 10 June sent a short congratulatory message to the British airmen. However, the new weapons could not stop Rommel’s troops, and the next day the French abandoned the fort, making a successful attempt to escape the encirclement. In fact, the Battle of Gazala could have been an even greater defeat for the Allies had it not been for the heroic defence of Bir Hakeim, which delayed the advance of Axis forces by nine whole days.

The Flight into Egypt

The extent of the Allied defeat at Gazala, suffered in the course of fighting in which the enemy made full use of his superior manoeuvrability, is exemplified by the fact that on 17 June the squadron had to flee from enemy tanks attacking Gambut to the airfield of Sidi-Heneish, located some 350 km east, and then, in stages, another 250 km to airstrip L.G.91 near Alexandria. In addition, the surrender of Tobruk fuelled Rommel’s offensive, both literally and figuratively.

Hurricane IID with No. 6 Squadron badge. Still from the Imperial War Museum film, used under the right to quote

Although in late June 1942 the British 8th Army experienced a fresh defeat, this time at Mersa Matruh, and was forced to retreat to the last line of defence in Egypt, at Al Alamein, the airmen of No. 6 Squadron RAF could look back on the passing month as a period of continued success. They reported the destruction of twenty-nine tanks (including self-propelled armoured guns) and forty-four other vehicles (trucks, bowsers and armoured cars). All this was achieved for the complete loss of three aircraft, while several were damaged. Flight Lieutenant Philip Snowden Alexander “Pip” Hillier, who claimed seven and a half tanks and no less than eleven other vehicles destroyed, for which he was awarded the DFC, and Wing Commander Roger Porteous, who reported the destruction of five and a half tanks and eight other vehicles, led the rankings. Unfortunately, the squadron also made a tragic mistake, when on 12 June it attacked friendly forces, destroying two armoured cars and a tank.

Press article about Philip Hillier’s decoration with DFC

Rommel’s troops, however, exhausted their offensive potential and the next month finally brought with it a change in the strategic situation. Extended supply lines and the losses suffered since the start of full-scale fighting in May 1942 began to tell on the Germans, and the following battle – the First Battle of Al Alamein – ended the series of Axis victories. Obviously, the pilots of No. 6 Squadron RAF continued to play an important role in the fighting. They added fourteen more tanks and a dozen other vehicles to their tally of victories, for the price of two Hurricanes destroyed and one pilot killed in action.

But later on in the month, although their purple patch continued, considerably more of the anti-tank Hurricanes experienced damage. Even a seemingly innocuous hit to the oil tank or cooler could result in the loss of an aircraft. The is no doubt that Axis forces started to give due consideration to the Allied aerial threat, and learned to combat it more effectively. An example would be the attack launched by No. 6 Squadron RAF on 13 July, when four out of the six participating Hurricanes were hit by flak. After this action, the Repair and Salvage Unit dismantled the wings of BN841, flown by Pilot Officer Petersen, which had crash-landed. Doubtless it was thought that they could be used to convert another Hurricane to the Mk.IID version. A similar situation had already occurred in the previous month. However, I do not have any data actually confirming this, i.e., that a pair of wings were used to “make” a Mk.IID.

No. 6 Squadron Hurricane IID in flight over the Western Desert, 1942. Photo: Imperial War Museum/Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

One method of defending tanks during stops consisted in manning shallow trenches with soldiers armed with machine guns; pointing their weapons straight up, they would send long bursts into the sky in the hope that at least some of the bullets would hit an aircraft flying overhead. Thus, the British introduced a jinking manoeuvre, which was performed after the attack so as not to fly directly over the target and thereby avoid this unpleasant surprise. One of the factors contributing to the success of the “Tin Opener”, as the cannon-equipped Hurricane soon came to be known, was the weakness of enemy air defences – especially in the first period of activity of No. 6 Squadron RAF.

This did not mean, however, that Allied pilots faced no threat at all, and in fact the first combat death occurred on 14 July, when Flight Lieutenant Stanley Robert Fairbairn-McPhee, who had destroyed four and a half tanks and seven wheeled vehicles in the previous month, perished. Despite this loss, the fighting on that day was extremely costly to the enemy; among others, the Allies attacked an entire column of vehicles, and only one truck survived. One Italian M13 tank, two armoured cars and eleven trucks were all that remained on the battlefield.

Hurricane IID from No. 6 Squadron. Still from the Imperial War Museum film, used under the right to quote

August was a period of relative peace, when the parties to the conflict, weakened by more than two months of bloody fighting, focused on gathering their strength, and thus the squadron did not have many opportunities for action. Only one operation, on 9 August, resulted in the use of the Vickers “S” – with devastating effect for two enemy vehicles.

During this time, No. 6 Squadron RAF received a standing fighter escort. Top cover was to be provided by Hurricane Mk.IIBs from Nos 127 and 274 Squadrons RAF, while close escort duties were entrusted to No. 7 Squadron SAAF, which flew Hurricane Mk.Ias armed, among others, with special – and oft-times spectacularly used – anti-tank bombs designed by Millie Jefferies. This was the case on 1 September, when an attack launched by No. 6 Squadron RAF did not bring about the anticipated result, while one of the South African pilots achieved a direct and devastating hit with such a bomb on a German eight-wheeled armoured car.

Two more successful raids were carried out in the first week of September. On 2 September, Rommel’s assets were further reduced by another eight-wheeled armoured car and truck filled with infantry, and on the next day by five tanks and two further wheeled vehicles.

The following weeks were a time of rest and training, unfortunately disturbed by the tragic death of one of the section commanders. On 6 September, the unit took part in a demonstration of the combat capabilities of its aeroplanes before a propaganda newsreel team, which came to Shandur and made a film that can still be viewed today; incidentally, this material was used as the basis for developing the paint scheme of aircraft number BP158. Unfortunately, during the event one of the most experienced pilots, Flight Lieutenant Philip “Pip” Hillier, lost his life while attacking a training target. After the simulated attack, the airman pulled his fighter up too strongly and entered a high speed stall, crashing right in front of the team. This scene was obviously removed and does not appear in the film.

Watch “The Tin Openers” film on the Imperial War Museum website.

No. 6 Squadron RAF rejoined combat operations only on 29 September. The action showed good cooperation between the ground troops and aerial forces. The unit received the enemy’s exact location and dispatched a section of Tin Openers with a fighter escort; the Hurricanes duly destroyed three armoured vehicles that had been making life difficult for 4th Armoured Brigade. And even though these were not exactly the same armoured cars which had been indicated by the soldiers of the “Black Rats”, the mission was still a success.

Was Vickers 40 mm effective?

At this point it is worth considering the actual effectiveness of the Vickers “S”. The pilots sometimes reported the destruction of several tanks in the course of a single flight, and, overall, the number of successes increased. But how many of these vehicles were in fact hit? And how many of those hit were completely destroyed? Simply put, this was impossible to determine. And it was doubtless also the case that one and the same destroyed target was reported by two or more pilots. A pilot would attack from a minimum height and closely observe his target, focusing on hitting it and avoiding a collision with the ground, and would therefore be unable to be cognizant of everything that was happening around him, so aspects like “mutual verification” did not function optimally. Further, there was usually no time to check the results, because loitering within the range of defensive weaponry in order to observe the outcome of one’s attack was not particularly safe. And when Allied forces were in retreat, it was impossible to ask ground troops to assist in verification. We should also assume that, in some instances at least, the enemy vehicles were quickly repaired. Here I cite only what was reported by pilots and recorded in the squadron’s operations log book. These numbers are undoubtedly inflated, but it is difficult to assess the scale of the phenomenon.

No. 6 Squadron Hurricane IID. Photo: Imperial War Museum/Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Silence before the Alamein

During the first half of October there were only three operations, involving a total of eight aircraft, which increased the sum total of destroyed enemy vehicles by two tanks and several other vehicles. This was the silence before the storm – the Second Battle of Al Alamein – which began at the end of the month. Allied defeats in previous battles led to Rommel’s armoured troops having a large number of captured vehicles. The squadron regularly encountered Stuart and Crusader tanks marked with black crosses. On 24 October, the Tin Openers knocked out no less than six Stuarts, while two others were hit by the airmen of No. 7 Squadron SAAF. The second action of the day resulted in the destruction of seven more Stuarts and one Crusader by No. 6 Squadron RAF, while the South Africans accounted for an additional tank. Two days later, another enemy unit which used captured tanks was massacred, losing four Stuarts, two Crusaders, five armoured cars and a half-track transporter; some fell prey to three pilots from No. 7 Squadron SAAF who took part in the joint action. This attack was described by a German soldier taken prisoner in early November, who testified that of the twelve captured Stuarts that set out that day, six were hit and gutted by fire, while the others received numerous hits but remained mobile and managed to retreat to their own lines. One of them received no less than six hits, however it was still in running order, while another’s turret had been pierced right through. The man further stated that the appearance of the Tin Openers caused panic, especially as the air defences were poor, and the Axis air forces did not provide adequate support.

Successive attacks during the month were not as effective. On 28 October, Flight Lieutenant M. Levine’s Hurricane BP550 was heavily damaged by Italian Breda anti-aircraft cannons and barely returned to base, while the next day Pilot Officer D. W. Jones was forced to crash-land his BP136 in no-man’s land, where he was rescued by a patrol of the Household Cavalry.

Hurricane IID attacks! Still from the Imperial War Museum film, used under the right to quote

Whereas the Battle of Al Alamein was a great and unequivocal Allied victory. The area which they recovered allowed for an inspection of the locations where the Tin Openers had caught their prey, and elaborate documentation and reports on their combat effectiveness. The overall assessment must have been quite positive, and it is therefore somewhat strange that it was decided that the squadron would not be moved west, which meant that it did not take part in the pursuit of the defeated Afrika Korps and Italian troops after 3 November. Worse yet, in December the unit’s Hurricane Mk.IIDs began to be replaced with standard Mk.IICs, and it was ordered to abandon its tank-busting role in favour of boring anti-submarine patrols. By the end of the month, the squadron had only one fully operational aircraft armed with Vickers “S” cannons was retained; it was disposed of in January. The pilots, eager to combat the Axis ground forces, were not happy with this turn of affairs, but it was only in the last week of February that the unit once again began to receive Hurricane Mk.IIDs, with their number increasing to twenty-one in March.

1943 – go West!

In early March 1943, having spent the previous weeks (and the whole of January) some 2,000 km west of the base in Idku, the squadron arrived at Castel Benito airfield in Tripoli. Operational flights from Surman airstrip were commenced on 10 March 1943, and the day’s first action was carried out using six aircraft, while the second involved no less than fourteen. Until then, such a large formation had not been used. The enemy lost five Pz.III tanks, fifteen armoured cars and sixteen other vehicles for three Hurricanes damaged. Squadron Leader D. Weston-Burt recalled that the joy of success was so great that he intended to perform a victory roll over the airfield, however reason got the better of him – and probably saved his life. After landing, it was discovered that his aeroplane had a nine-inch-diameter hole in the left wing spar. Thus, the wing was only just hanging on, as at that point the spar was approximately ten inches wide.

The first action of the year, just as in the previous year’s début, consisted in providing aerial support for the Free French, this time under the leadership of General Philippe Leclerc.

Even greater success was achieved on 22 March, during the Battle of the Mareth Line in Tunisia. A total of twenty flights were carried out, and in their course thirty-two Pz.III and Pz.IV tanks and eleven other vehicles were hit. The Allies’ own losses amounted to four aircraft shot down, however the pilots survived. On 24 March 24, two operations of No. 6 Squadron RAF cost the Axis a further fifteen tanks and fifteen pieces of other wheeled equipment. However, the price of victory was higher, as this time round the anti-aircraft fire was both intense and accurate. Four Hurricanes were lost, one pilot (Sergeant F. Harris) perished, and two aeroplanes were damaged. On 25 March, ten Hurricanes launched an attack on a group of fifty German tanks, destroying eleven. But the cost of the victory was yet again immense. Six aircraft were shot down, all of the others suffered damage, while one airman, Pilot Officer J. B. Paton from New Zealand, was wounded. Despite the losses, eleven Hurricanes took off the next day, knocking out three trucks and a self-propelled gun for two aeroplanes lost and two damaged (the pilots of these aircraft returned to the unit uninjured).

By the end of the month, the Battle for the Mareth Line was drawing to a close. The pilots of No. 6 Squadron RAF had contributed immensely to the Allied success, and this found reflection in the congratulatory telegrams sent by Western Desert Air Command.

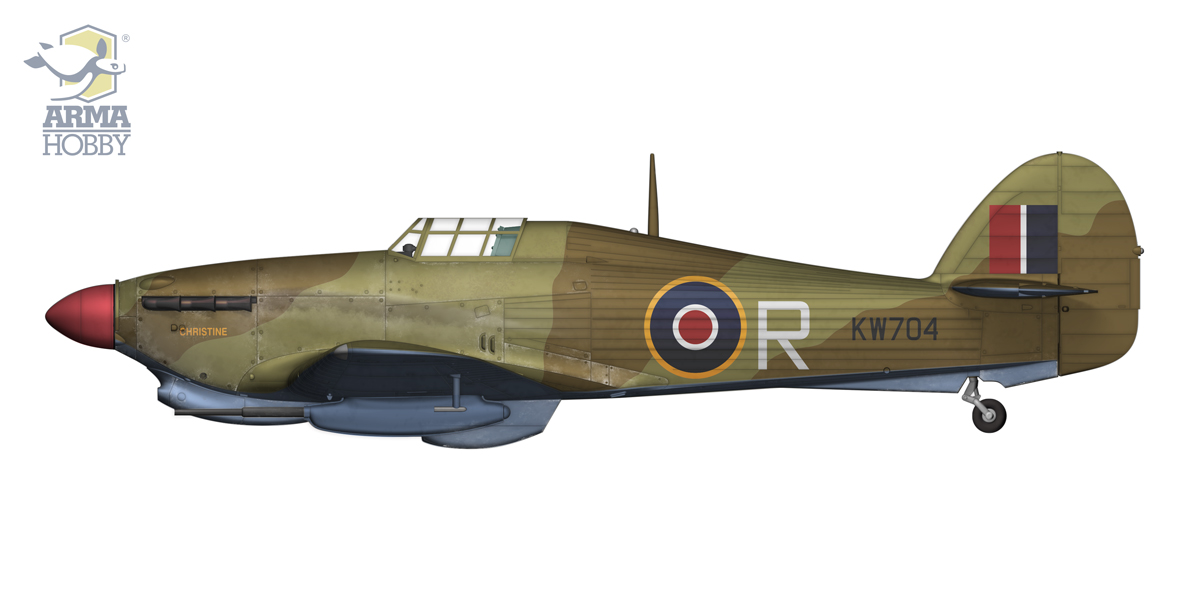

Hurricane IID HW704/R „Christine” in which F/O A.H.M. Clarke was killed

Final in Tunisia

The last stage of fighting in North Africa commenced in April. The Axis forces were by then pushed to the defensive in Tunisia, and nothing could reverse the course of events. When the Battle of Wadi Akarit began, the squadron was stationed at Gabes airfield. This was the last engagement in which the airmen of No. 6 Squadron RAF took part under the African sky. On 6 April, when the offensive started, they conducted three operations. During the first, no tanks were found and the attack switched to secondary targets, resulting in the destruction of four trucks. The second was also wasted, even though the pilots spent a good dozen or so minutes searching for targets worthy of the Vickers “S”. Nothing was found, and in addition the strong and accurate flak accounted for three Hurricanes. Pilot Officer T. Petersen and Flight Sergeant E. Hastings returned to the unit the same day, but the third aviator, Flying Officer M. Zillessen, was declared missing. Yet another painful loss. It was not until mid-June that the International Red Cross reported that the pilot had survived a landing in difficult terrain and was in German captivity. The third operation of the day slightly improved the overall balance, as the Hurricanes hit a Pz.III, a half-track transporter, and four trucks. Importantly, however, the losses suffered over the past few weeks began to affect pilot morale – despite the numerous successes that were reported at the same time. The next day, the cup of bitterness was filled to the brim. On 7 April, eleven aircraft took off. The start of the mission was photographed in colour at Gabès airfield. All hell broke loose on the approach to the target: the anti-aircraft defences put up a curtain of fire, at once destroying six Hurricanes. Three pilots lost their lives. Flight Sergeant Hastings, who had been shot down the day before, was now killed at the controls of HV560. Awarded the DFC for his previous achievements, Flying Officer J. C. W. Walter lost his life in HW651 before he could be presented with the medal. The third pilot, Flying Officer A. H. M. Clarke, flying on HW704/R with the name “Christine” (a reconstruction of the aircraft has been included in the Arma Hobby kit), also crashed into the ground. Three others managed to survive, but six aeroplanes shot down for one tank and two SdKfz half-track transporters hit was a very high price. The loss of three pilots in one missions – when six had perished in all combat flights until that time – greatly strained the endurance of the exhausted aviators.

No. 6 Squadron Hurricane IID “R” taking off on 7 April 1943. Close-up detail from the Imperial War Museum photo, used under the right to quote

The unit was soon moved to Bou Goubrine airfield, from where it chased the constantly advancing front, but it did not rejoin the fight until 20 April. But again, no targets were found that day. The next and final action of the month – and for the Mk.IIDs as such – took place on 28 April. The unit, commanded by Squadron Leader D. Weston-Burt (just as on the ill-fated mission of 7 April), did not launch an attack. The commander concluded that the enemy’s anti-aircraft defences were too strong. He must certainly have had the horrific events of three weeks past fresh in the memory, and decided not to expose his pilots to equally tragic losses.

At the beginning of May, work started on summarizing the squadron’s tank-busting operations. The non-optimal cooperation with land forces, which led to an overall decrease in efficiency, was duly noted. It was further observed that losses in equipment and pilots tended to be huge when the enemy had any defences worthy of the name, and that these losses impacted pilot morale, necessitating the immediate discontinuation of operations. Ultimately, experiences gathered during the use of the Hurricane Mk.IID on the African front did not lead to a wider use of specialized weaponry of this type. In the demanding European Theatre of Operations, no units armed with this version of the Hurricane were employed in combat, and all existing models were sent to the Far East.

No. 6 Squadron RAF returned to action in March 1944, taking off from airfields in southern Italy. It flew on the Hurricane Mk.IV until the end of the war.

See also:

- Order Hurricane Mk.IID model kit online in the Arma Hobby webstore

Hurricane Mk IID – części 3D i modyfikacje – porady modelarskie

Model maker for 45 years, now rather a theoretician, collector and conceptual modeller. Brought up on Matchbox kits and reading "303 Squadron" book. An admirer of the works of Roy Huxley and Sydney Camm.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski