There is no doubt that from among all the pilots of the 1st Fighter Group who operated the P-51B (354th Fighter Group), the most famous was James Howell Howard – even though he was not the unit’s leading ace. Other airmen, such as Glenn Eagleston, Don Beerbower and Jack Bradley, achieved a great many more aerial victories. So where does his fame come from? It was all due to a spectacular mission that took place on 11 January 1944, during which Jim Howard for half an hour solitarily defended a box formation of Flying Fortresses from 401st Bomb Group against successive waves of Luftwaffe fighters. For this exploit, he later received the highest American award for valour – the Congressional Medal of Honor – as the first-ever Mustang pilot. But his second extraordinary achievement is much less known. Namely, he became the first ace to fly the P-51 with the Packard Merlin engine, and was also the first ace of the renowned 354th Fighter Group. And to think that Howard was well on his way to spending his entire flying career in China! If not for a coincidence, Jim would never have been posted to Europe.

Volunteering for China

China? How come? First and foremost, James Howard was born in China, where his father, a professor of ophthalmology, lectured at the Medical Academy in Beijing. That is where he spent the first 14 years of his life. For him, China was home. When he returned with his family to the United States, he initially planned to follow in his father’s footsteps and study medicine, however the call of adventure proved too strong to resist, and he decided to enlist in the US Navy instead. Following pilot school, he flew with a number of squadrons, among others on the USS Enterprise. In 1941, while serving on the carrier, he learned that Claire Chennault was organizing a group of volunteers, or – to apply a more precise definition – mercenaries, who would fly Chinese aeroplanes (specifically Curtiss H-81s purchased by China, which the British called “Tomahawks”) against the Japanese to defend the Burma Road that supplied China from the south. For him, this was a unique opportunity. Dogfighting in the sky, and not only for a just cause, but also in China, which he knew so well from his youth. Howard duly resigned his commission and signed a contract with Chennault.

James H. Howard and American Volunteer Group pilots at Curtiss P-40 B, China 1942. Photo www.thisdayinaviation.com.

Début Above Burma

However, when the pilots of the newly formed 1st American Volunteer Group gained combat readiness, the war had already caught up with the United States, and the whole of East Asia was engulfed in conflict. Together with his fellow ex-US Navy pilots, Howard was assigned to John Newkirk’s 2nd Pursuit Squadron, known as the “Panda Bears”. But at more or less the same time the Japanese limited their operations in China and instead focused on the south-west, from Thailand to Burma and from Malaysia to Singapore. Thus, Chennault would send squadrons one by one to support the British in Burma, where the fate of the Burma Road would be decided. Howard and the 2nd Pursuit Squadron were initially stationed in China, and so the brunt of the fighting in Burma was borne by the 3rd Pursuit Squadron (“Hell’s Angels”). By the end of 1941, the 3rd Pursuit Squadron was seriously depleted, and Chennault therefore dispatched the “Panda Bears” to Burma. During his first combat mission, Howard reported destroying four fighters that had just landed at Raheng Aerodrome (Ki-27s from 77 Sentai) and having avoided being shot down by other Ki-27s – still airborne – by a miracle. Howard’s bacon, so to speak, had been saved by “Tex” Hill. After the event, another famous mercenary from the American Volunteer Group, Gregory Boyington, called Howard an “automatic pilot” who always performed his tasks no matter what.

On 19 January 1942, while attacking Mae Sot Airfield, three pilots from the 2nd Pursuit Squadron noticed a small reconnaissance aeroplane and duly shot it down. One of the trio was Howard, who thus achieved his first shared kill. Just a few days later, on 24 January, Howard’s section intercepted a group of Japanese bombers making their way to Rangoon and tied down their Ki-27 escorts from 50 Sentai; soon after, Jim recorded his first solo kill. Worn down by the constant fighting, the squadron was then sent to China to rest. Once the situation in Burma had quieted down, the Japanese returned to the offensive in China, and on 4 July 1942, a day after the official disbandment of the American Volunteer Group, Howard downed another Ki-27 while flying a P-40E over Hengyang.

In theory, the demobilization of the Group was intended to enable the transfer of its pilots to the USAAF’s 23rd Fighter Group. But the army bureaucrats planned to achieve this in such a blunt and unceremonious manner that hardly any of the mercenaries obliged. Although Howard was offered the rank of major and command of the squadron, he too refused. He later explained that at the time he was tired, had had enough, and was also going through a bout of dengue fever. Instead, he returned to the United States. In this way his ties with the Middle Country were severed for good.

P-51 B-5 Mustang “Ding Hao” flown by James H. Howard, początek 1944. Note an early canopy changed later to the Malcolm Hood. Photo: wikipedia.

A New Front and New Aircraft

Back home, however, Howard nevertheless enlisted in the USAAF, albeit on reduced terms – as a captain. After serving a few months at a flying school, he was recommended for command of the 356th Fighter Squadron in the 354th Fighter Group, which was getting ready to enter the war still operating its Aircobras. But when the unit docked in Liverpool on 1 November 1943, it received a fleet of brand-new P-51Bs. It was assigned to Ninth Air Force, which was to support the planned Allied invasion. Army officials approached the P-51B as simply a newer version of the P-51A/A-36, which had proved itself in the ground attack role. It soon transpired, however, that the Packard Merlin engine had breathed new life into the Mustang, turning if from a low-level close air support aircraft into a proper escort fighter with great range and a high operating ceiling. This was noticed by the command of Eighth Air Force, at the time suffering heavy losses, whose Thunderbolts were unable to provide effective cover for its Flying Fortresses and Liberators due to their insufficient range. In consequence, the 354th Fighter Group was lent out to the Eighth Air Force. The Mustang pilots rapidly began taking a toll of the enemy.

They gained their first victories already in mid-December, and the 354th Fighter Group fought its first large-scale aerial battle on 20 December 1943. On that day 500 bombers from all three Commands of Eighth Air Force attacked the port in Bremen. The Mustangs were to take over escort duties from the Thunderbolts over the target and then escort the “big friends” back home. Between Wilhelmshaven and Bremen, the bombers came under ferocious attack from groups of single- and two-engined Luftwaffe fighters. During the mission, the 354th Fighter Group was led by the highly experienced Don Blakeslee from 4th Fighter Group, while Howard commanded only a pair of Mustangs. When the enemy made an appearance, Jim and his wingman proceeded to fight them off, however taking care not to stray away from their charges, and so without pursuing the Germans just to gain a confirmed kill. But when he saw three Bf 109s attempting to dispatch two damaged B-17s, he caught up with them and shot one down with his first burst. This was Howard’s first kill achieved in Europe. For the next few missions he commanded the entire squadron. And although he did not achieve any more victories, he came to be recognized as an excellent tactician who reacted expertly to enemy attacks on American bomber formations.

P-51B-1-NA Mustang (43-12433/AJ-M, “Miss Pea Ridge”), 356th Fighter Squadron, 354th Fighter Group, pilot Mack Tyner, early 1944 r. Photo wikimedia commons.

The January Mission Over Germany

On 11 January 1944, Eighth Air Force was ordered to send all three of its Commands to attack various targets located deep in Germany. But bad weather dashed these plans, and both the 2nd Command (B-24 Liberators) and 3rd Command (B-17 Flying Fortresses) had to turn back to base. Only the 1st Command (B-17 Flying Fortresses) continued on the mission, heading for the industrial areas of Oschersleben and Halberstadt. Soon, it attracted the fury of the Luftwaffe units defending the Reich. The majority of the American fighters had returned to England with the 2nd and 3rd Commands, and so the 1st Command was escorted only by four groups of Thunderbolts and the 354th Fighter Group, flying Mustangs. Worse still, the target was located at such a distance that towards the end of the flight the P-47s had to hand over the mission to the P-51 pilots. The 354th Fighter Group was therefore left alone on the battlefield to fend off a numerically superior hostile force.

Richard Turner, Howard’s subordinate, who would become the most successful ace of the 356th Fighter Squadron, recalled the situation thus: “(the enemy aircraft) taking off from the ground resembled swarms of bees. It seemed as if they were coming in from all directions, some 10,000 feet below the bombers, which were flying at a height of 17,000 feet”.

„Zgłaszam jeden ME 262 zestrzelony” – historia Jerzego Mencla i jego Mustanga III

On this mission, which was rapidly becoming more and more difficult, Howard was in command of the entire 354th Fighter Group. Anticipating the development of the situation, Jim deployed his meagre force with typical meticulousness. One squadron was instructed to defend the centre of the formation, another the end, while the 356th Fighter Squadron was ordered to protect the front. As it transpired, the Germans focused on the latter, which was made up of aircraft from 401st Bomb Group. Initially, keeping his cool, Howard sent section after section to relieve the “boxes” of Flying Fortresses, however the enemy was just too numerous. Soon the commander was forced to enter the fray with his own section.

At 11:50, Howard flew towards a twin-engined Bf-110 that was approaching the leading squadron of bombers from behind. The Mustang pilots dropped their auxiliary fuel tanks and quickly got onto the Messerschmitt’s tail. From a distance of approximately 200 metres, Jim started firing off long bursts, hitting both engines and the fuselage in the vicinity of the cockpit. His wingmen also opened fire, however they missed. But after Howard’s attack the Messerschmitt banked and started diving earthwards, falling to pieces just before hitting the ground. Howard immediately started to climb in order to get back to the bombers.

“Flying fortress” from 401st Bombardment Group, early 1944, photo: wikipedia.

A Lonely Fight

Having gained altitude, he suddenly realized that he was completely alone. The pilots from his section had somehow got lost, while the other sections were battling the Germans further away. Undaunted, he returned to his task: protecting the bombers at all costs. Within a minute or two he saw a Focke-Wulf FW-190 making its way towards the Fortresses. Since the enemy was flying at a slightly higher altitude, the American pulled delicately on his stick and, climbing, approached the German from behind. The FW-190 was unable to see him and continued in the direction of the B-17s. Intending to chase the enemy off, so as to prevent him from getting into a shooting position, Howard pulled the trigger from a considerable distance – more or less 450 metres. But to his surprise, his burst was bang on target! Pieces fell off from the Focke-Wulf, and the panicked pilot immediately drew back the canopy and jumped with his parachute!

Not more than five minutes later, Howard observed a Bf 109 closing in on the formation. It was already being followed by another Mustang, however the American pilot seemed to have trouble keeping up. Howard rushed to his aid, but for some reason his comrade abandoned his attack. In the meantime, the Messerschmitt pilot noticed Howard, slowed, and proceeded to perform a scissors manoeuvre, intending to get onto the tail of his P-51B. When Howard feinted, the German tried to engage him in a classic dogfight. Extending his flaps, Howard soon gained the upper hand, and so the Bf 109 made an attempt to flee. Jim caught up with him, however, and pressed the trigger. But he was in for a rude surprise: two his four Brownings failed to operate. A few bullets hit the Messerschmitt, however they failed to do sufficient damage. Not intending to abandon his charges, Howard turned back to the Flying Fortresses.

Lt.Col. James Howard in his P-51 B Mustang cockpit, April 1944. Note new Malcolm hood canopy. Photo wikimadia commons.

At 12:10, Jim observed yet another attacker approaching the bombers. This time it was a Bf 110. The enemy was flying slightly lower, and so he pushed on his stick; soon, the Messerschmitt filled his sights. Fire! But something was terribly wrong! Only one machine gun was working! Nevertheless, his bullets hit the Bf 110. The German fighter turned on its back and fell towards the ground. Black smoke billowed from its engine, in seconds accompanied by clouds of glycol. Seeing that his enemy was in a vertical dive, the American pulled up his fighter and turned back to the bombers.

Five minutes later, Howard was going full throttle towards another Bf 109 that had ventured towards the Flying Fortresses. Aware that he was at a disadvantage in armament, he focused on getting as close to his enemy as possible. Finally, however, the German pilot noticed him and, turning his aircraft on its back, dived. Howard chased after him for a while, shooting steadily. The Bf 109 started to disintegrate in mid-air, and it was clear that the pilot had lost all control. But Jim, acutely conscious of his duty, did not follow him down to see him crash, and quickly returned to the bombers. Howard chased off successive attackers without even shooting. Bluffing, he did everything in his power to protect the Flying Fortresses. On at least two or three occasions, the German fighters were forced to abandon their prey and retreat with their tails between their legs.

Mustang J. H. Howarda in aerial combat, April 1944. Artwork by Piotr Forkasiewicz.

Three Confirmed, One Probable, One Damaged

Finally, the sky quieted down. The Flying Fortresses turned back to England, while the Mustangs regrouped and reformed in formation. They had been fighting hundreds of enemy aircraft for a full hour! Back home, they were awarded 15 confirmed kills and 7 probable, and an additional 9 Luftwaffe fighters damaged. The Germans had not managed to shoot down a single P-51. But the battle had proved to be very costly for the bomber crews. No less than 42 B-17s did not make it back to base, for various reasons. The majority were lost to German fighters. If only there had been two or three Mustang Groups… But this was something that the enemy was to experience in a few months. Howard himself reported two confirmed kills, two probables and one damaged. Command, however, displayed an unexpected and unusual approach, raising his tally to three confirmed, one probable and one damaged. Following an analysis of his gun camera footage (and also, in all probability, after interviewing the bomber crews) his superiors came to the conclusion that the Bf 110 which had been seen diving with a trail of black and white smoke had actually been destroyed.

The mission turned Howard into a living legend. The records of 401st Bomb Group describe his exploits thus: “The Mustang pilot was completely alone when one of the wings in the formation was attacked by a swarm of 30-40 German fighters. Instead of retreating and abandoning us in the face of such overwhelming odds, the pilot of the P-51 threw himself at the Germans without any hesitation. For the next 20 minutes the bomber crews witnessed one of the greatest displays of courage that they had ever seen”.

Gen. Spaatz, Commander of US Strategic Forces in Europe with Lt.col. James Howard, 1944. Photo wikipedia.

New Missions, Fresh Victories, Successive Promotions

In subsequent campaigns, Howard both commanded and fought, building up his reputation. On 30 January 1944, during the bloody fighting over Brunswick, he shot down a Messerschmitt Bf 110. This was his seventh individual aerial victory, and the fifth achieved on Mustangs. On that day James Howell Howard became the first P-51B ace. On 12 February 1944, following the loss of the commander of the 354th Fighter Group, Colonel Kenneth Martin, Howard was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and placed in charge of the entire Group. He served in this capacity until April 1944, while on the 8th day of that month he gained his last – eighth – solo kill. A few days later, he was transferred to the Headquarters of IX Fighter Command. His experience proved invaluable during work on the operational strategy of the fighter groups of Ninth Air Force for the upcoming Normandy invasion. Finally, in September 1944, Howard completed his tour of duty and returned to the United States.

In subsequent campaigns, Howard both commanded and fought, building up his reputation. On 30 January 1944, during the bloody fighting over Brunswick, he shot down a Messerschmitt Bf 110. This was his seventh individual aerial victory, and the fifth achieved on Mustangs. On that day James Howell Howard became the first P-51B ace. On 12 February 1944, following the loss of the commander of the 354th Fighter Group, Colonel Kenneth Martin, Howard was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and placed in charge of the entire Group. He served in this capacity until April 1944, while on the 8th day of that month he gained his last – eighth – solo kill. A few days later, he was transferred to the Headquarters of IX Fighter Command. His experience proved invaluable during work on the operational strategy of the fighter groups of Ninth Air Force for the upcoming Normandy invasion. Finally, in September 1944, Howard completed his tour of duty and returned to the United States.

Photo: Tomb of Brig. Gen. James Howarda, Arlington VA. Photo wikipedia.

Back home, he was greeted as a hero, all the more so when President Roosevelt presented him with the Congressional Medal of Honor in recognition of his exploits of 11 January 1944. Howard resigned his commission shortly before the end of the war. Understandably, he was tired, and he wanted to start a family and lead a normal life. A few years later he set up a company. His business prospered, at one point employing as many 350 people, and he sold it just before retiring. James Howell Howard died at the age of 82 as a very wealthy man.

English translation: Maciek Zakrzewski

See also:

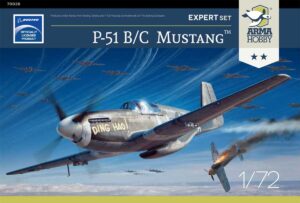

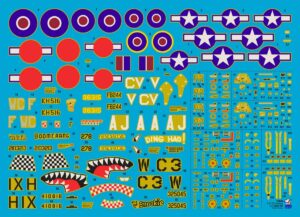

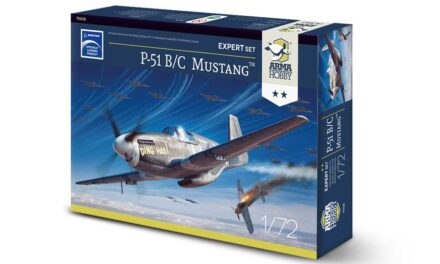

- P-51 B/C Mustang™ model kits in Arma Hobby Internet shop link

- Photos of the P-51B AJ-A on website AmericanAirMuseum link

The “Saints” Squadron – US Navy most successful Wildcat unit

A keen modeller since childhood. He is mainly interested in aviation from the times of the First and Second World Wars. He made about a hundred models, wrote a few books and several dozen articles.

Apart from modeling, he is passionate about history, not only the latest one, but also a very distant one. He loves to read journalism, scientific books and science fiction novels. All the time he grumbles that a day should be 50 hours long and he forces himself to go to sleep.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski