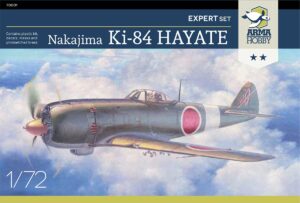

In order to present the story of our heroine properly, we must anticipate the facts a bit and start from the end. The Hayate originally marked with the white tactical number “46” is the only representative of the Ki-84 family that exists to this day. The lively old man (who turns 78 in 2022) is still in a very good condition, and after some preparation could take to the air again. What is more, it is not a machine that was taken over after the war in the Nakajima plant, but a real veteran that participated in the fighting for the Philippines in the autumn of 1944.

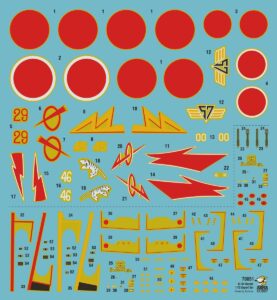

Knowing the broader context, we can move on to the details. The Ki-84 Ko with serial number 1446 left the Nakajima plant in Ota in the summer of 1944 (probably on 26 June). Following a test-flight and the introduction of a number of necessary technical corrections, it was transferred to Tokorozawa airport north-west of Tokyo. Tokorozawa is a historic airfield which once housed the Army Aviation Research and Development Centre of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF). It was also home to numerous operational training units, as well as a technical and logistic centre where both seasoned and newly created Sentais (groups) were sent to replace their equipment, change over to new aircraft types, undergo additional training, and regain full combat worthiness. And it was there for that the personnel of 11th Sentai, one of the oldest and most distinguished units of the IJAAF, waited impatiently for its brand new Hayates. The machine was marked with the unit’s emblem – a lightning bolt. It was red in colour (with a white edging), and thus symbolized affiliation to 2nd Chutai of 11th Sentai (in other words to No. 2 Squadron of 11th Group). In accordance with the methodology often employed by the IJAAF, it was assigned the tactical number “46” – the last two digits of its serial number.

The Tribulations of War

The rich history of 11th Sentai is worthy of separate discussion, and here I will focus only on the period when the Ki-84 Hayate were the unit’s basic combat tool. Between the summer of 1943 and the spring of 1944, the 11th operated in the CBI (China-Burma-India) Theatre. Its combat trail led from Harbin in Manchuria, through Wuhan in central China, and to Canton in the south-east of the country. And it was there that in March 1944 the unit received an order to withdraw to Japan for re-equipment and reorganization. At the time, 11th Sentai was considered an elite unit, and rightly so. Its ranks were full of experienced pilots. Many fliers had taken part in the bloody New Guinea campaign and fought in the skies above the Solomon Islands. A few still remembered the clashes over Malaya, Burma and the Dutch East Indies in 1941–42. The switch from the currently used Ki-43-II Hayabusa to a state of the art fighter aroused both hope and enthusiasm. War, however, is governed by laws of its own. Shortly after arriving in Tokorozawa, most of the experienced pilots had to leave the home regiment. Some were transferred to other units, where they appointed squadron or section commanders. Others were sent to training units as aerial combat instructors, while others still, carrying injuries and exhausted by tropical diseases, were granted lengthy leaves of convalescence.

Only the core of the Sentai’s cadre remained at base, supplemented with hastily trained novices. For these rookies, the transition from the antique Ki-27s or the heavily worn Ki-43s to the Hayate was no easy task. The numerous technical shortcomings of the early Ki-84s did not make matters any easier. To make matters worse still, the Headquarters itself (Koku Hombu) could not decide where and how to use the reorganized unit. Initially, plans were made to attach it to the Japanese Homeland Air Defence (Hondo Boei Butai), while later it was proposed that it be sent to China in support of the decimated 25th, 50th and 85th Sentais. In the end, it was decided to dispatch the unit to Formosa (Taiwan), where it was to temporarily strengthen the island’s defences, while following the anticipated invasion of the Philippines it would be immediately moved to Luzon. In accordance with the initial plan, the Sentai was to depart for Japan in early September. But the insufficient level of training of its young pilots resulted in this date being postponed by a month. Finally, on 10 October 1944, forty Hayates from 11th Sentai took off under the command of Major Yoshihiro Kanaya. Not everything went according to plan. Several aircraft had to turn back due to technical reasons, and two pilots went missing while flying over the ocean. About thirty of the fighters arrived at Yilan Airport in Taiwan. Their “acclimatization” at the new location was not supposed to take long.

„White 46” left on the Clark Field airbase, Philippines. Photo: US Army.

Taiwan…

While preparing for the invasion of the Philippines, American intelligence determined that the Japanese had a force of some 1,000–1,200 aircraft of various types in the planned area of combat. About 450 in the Philippines, 350 in Taiwan, and the rest in Okinawa and bases in southern Kyushu. The mission to neutralize these forces early was entrusted to the aircraft carrier attack group of Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, known as Task Force 38. It was a giant fist comprising eight fleet carriers (CV), nine light aircraft carriers (CVL), six fast battleships, six heavy cruisers, eight light and anti-aircraft cruisers, and fifty-eight destroyers and numerous support vessels. The seventeen aircraft carriers boasted a total of nearly 1,000 aeroplanes. All this might (backed up by a B-29 attack from China) crashed down on Taiwan on 12 October 1944.

That day, 11th Sentai was kept in reserve almost to the very end. It was sent into combat only in the final phase of the battle, against enemy planes retreating to their floating airfields. The result was a brief but extremely fierce clash with the Hellcat fighters of VF-19 squadron from USS Lexington, which constituted the Allied rearguard. About twenty-five Hayates engaged the slightly more numerous F6F-5s. The Americans lost three fighters and three pilots (including the unit commander), however the price that the Japanese had to pay for their success was extremely high. Six Ki-84s were shot down, and two more returned to base so shot up that they had to be written off. Most of the other fighters were damaged as well, and this was a serious problem in the absence of spare parts. The loss of trained pilots was even more worrying. Six airmen were killed, including three young fliers, two Chutai commanders and … the Sentai commander. Two of the unit’s veterans were seriously injured. Lieutenant Hironojo Shishimoto (an ace with seven confirmed and seven probable kills) severely damaged one Hellcat, but a moment later he had to bail out of his burning aircraft. Dangling in his parachute, the Japanese aviator became a target for a pair of American fighters. Major Kanaya came to the rescue and drove his attackers away, however he himself perished after being attacked by four F6Fs providing top cover. Severely wounded by 0.5 inch bullets, Shishimoto was rescued and underwent a full year of rehabilitation. He did not return to flying, and this event (paradoxically) allowed him to survive the war. Thus, at the very beginning of its current campaign the unit had lost eight aeroplanes and eight pilots – five of them very experienced. Command of 11th Sentai was assumed by Captain Yuji Mizoguchi, the squadron leader of 3rd Chutai.

Another view of the Ki-84 abandoned on Phillipines

Another view of the Ki-84 abandoned on Phillipines

…and Phillipines

On 20 October 1944, the US 6th Army began landing on Leyte. 11th Sentai was ordered to the Philippines and set off two days later. Due to numerous mechanical failures, initially only seven Hayates arrived at Luzon. The next day, five more flew in, and another four the day after. These sixteen fighters were no longer a force comparable to the forty Hayates that had left Japan just two weeks earlier. The first combat mission over the archipelago turned into a fiasco. A dozen or so Ki-84s from the 11th and 1st Sentais were to provide cover for a large group of bombers from 3rd Sentai. However, the regional headquarters was in an unbelievable mess, and the Hayates arrived at the assembly point long after the bombers had left, completely alone. For some time, the group circled, awaiting the returning bombers (3rd Sentai’s attack ended with the unit’s nearly total annihilation), and later decided to return to Malacat airport. Between 23 and 26 October, Leyte Gulf was the scene of a major clash of Japanese and American air and naval forces. 11th Sentai did not participate directly. Its task was to defend the area of Clark Field – Lipa – Malacat, i.e. the key bases near Manila. There were a number of encounters with P-38 Lightnings and P-47 Thunderbolts, in which the unit lost three aeroplanes and two pilots, claiming four-six victories.

Despite suffering relatively small losses, towards the end of the month the group had no more than two or three combat worthy fighters. 1st Sentai was in the same situation, and both units were withdrawn to the homeland in order to re-equip. They returned to the Manila area rather quickly, with the aircraft of the “new” 11th Sentai touching down on Clark Field already around 7–8 December. Yet again, the “demons of the past” reared their heads as of the forty machines that took off from Japan, only one half reached their destination. The white “46” was among them. As Clark Field itself (a former US base) was very well known to the Americans and was under constant attack from the air, the unit moved to the nearby Porac airfield, which was much less exposed. On 17 and 18 December, the Sentai was sent on a mission against the port and airfield of San Jose on the island of Mindoro, which was in the course of being occupied by the Allies. On the first day, the commander of 1st Chutai, Captain Kawagoe, perished over the target, while on the second day the commander of 3rd Chutai, Captain Ikeda, who had previously reported two “kills”, failed to return to base. On 20 December, the unit provided cover for “toko” suicide aeroplanes. Surprisingly, the 11th did not suffer losses, while its “charges” sank one and seriously damaged another troop transport.

Until the end of December, Hayate units twice more flew cover for “toko” attacks, and they also took part in night fighter-bomber missions against American bridgeheads on Luzon. These tasks entailed a strong response from both enemy fighters and anti-aircraft artillery. As on 6 January, the unit had only six aircraft (of which three or four were combat worthy); by 9 January, this number had fallen to zero. On 14 January, 11th Sentai’s remaining personnel left for Taiwan on a transport aeroplane. In early March 1945, the survivors arrived at Takahagi on the Kanto Plain in Japan. The plan had been for the unit to be rebuilt, however most of the aeroplanes and young pilots were soon sent to the suicide units being thrown into the Battle of Okinawa. The 11th did not “rise from the dead”. The white “46”, damaged and abandoned, with the emblem of its once proud unit, had been left on the outskirts of Clark Field. The next stage of its history would soon begin.Do końca grudnia Hayate jednostki jeszcze dwukrotnie osłaniały ataki „toko”, kilkakrotnie uczestniczyły też w nocnych misjach myśliwsko-bombowych na amerykańskie przyczółki na Luzonie. Podobne zadania wiązały się z silną odpowiedzią ze strony myśliwców wroga, jak również ognia obrony przeciwlotniczej. Stan jednostki na dzień 6 stycznia wykazywał zaledwie 6 maszyn (z czego 3-4 zdolne do walki), a 9 stycznia już zero. 14 dnia tego miesiąca, niedobitki 11. Sentai odleciały na Tajwan na pokładzie samolotu transportowego. Na początku marca 1945 roku, ocalały personel Sentai dotarł do Takahagi w stołecznej dolinie Kanto w Japonii. Tu miał dać początek kolejnej odbudowie, ale… większość maszyn i młodych pilotów trafiać poczęła do jednostek samobójczych rzucanych do bitwy o Okinawę. 11-ta nigdy już nie „zmartwychwstała”. Uszkodzona i porzucona „biała 46” z godłem dumnej niegdyś jednostki, pozostała na obrzeżu Clark Field, aby rozpocząć kolejny etap swojej historii.

In Foreign Hands and tests

In Western publications, the date of acquisition of the white “46” is given with considerable imprecision. Some mention January, while others February or even March 1945. Interestingly, each of these pieces of information is in a sense true. Namely, everything depends on whether we are talking about the finding of the aeroplane by American infantrymen, the date on which it was taken over by intelligence, or the beginning of flight tests. As many as six large tactical units equipped with the Hayate (1st, 11th, 22nd, 51st, 52nd and 200th Sentai) took part in the defence of the Philippines, however only two flight-worthy Ki-84 Ko fighters were captured by the American (which, incidentally, is testament to the destructive power of the invasion). The matter was urgent, as the Allies knew little about the actual capabilities of the IJAAF’s new fighter. True, they had already encountered it in August in China, but the pilots usually reported clashes with “some new Zero variant” or – at best – with a “Ki-44 Tojo variant”. For them, the mass appearance of the Ki-84 over the archipelago was an unpleasant surprise.

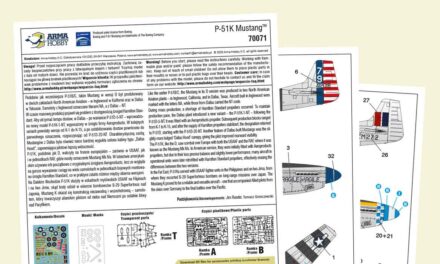

Specialists from the Technical Air Intelligence Unit – South West Pacific Area (TAIU – SWPA) immediately became involved. Both Hayates had their camouflage removed and were marked with American stars and the “trophy” codes S10 and S17. S10 appeared to be in a state of better repair, however it was discovered that it had numerous factory technical flaws, and, after the removal of all useful components, it was scrapped. Whereas the white “46” (i.e. S17) made several flights, and these became the basis for elaborating a circular letter informing aerial units from all divisions of the armed forces of the approximate performance of the Ki-84. The Americans were, however, aware that the parameters which they had determined did not exhaust the target capabilities of the structure. The aeroplane required a thorough overhaul and/or repairs in order to arrive at a full validation of the data. S17 was therefore loaded onto the escort carrier USS Long Island (CVE-1) and shipped to the United States. Wright Field, Ohio, became its new home. Although this occurred only in the spring of 1946, when the war was well and truly over, it was decided to continue the trials. S17 underwent extensive work. The engine was completely disassembled, the cylinder head sanded, and the spark plugs and wires were replaced, while the fuel system was adapted to use American oil and high-octane fuel. All rubber elements (of terrible quality) were also replaced, starting with the tires and ending with the seals. The Hayate’s traditionally unreliable main undercarriage was repaired and supplemented with specially made high-quality steel details, the braking system was improved, etc. Once these modifications were complete, the aeroplane was finally able to demonstrate its true potential, offering parameters superior to those it had when leaving the production line. But relatively few flights were performed on S17 (May-June 1946). The reason was that two more of the aircraft had arrived at Wright. These were a brand new Ki-84 Ko and Otsu which had been found in the factory hall in Utsonomiya shortly after the end of hostilities. Tests focused on this due, while the previously white “46” was duly secured and placed in storage.

On board of the USS Long Island heading to America, Photo: U.S. Navy.

Tests in the Wright Field

…in Museum and on Air Show

A few months later, President Harry Truman established the Smithsonian’s National Air Museum (NAM), today known as the National Air and Space Museum (NASM). The Army, ridding itself of a whole mass of “war trophies”, donated S17. The problem, however, was that the NAM was still in its infancy, and struggling with the lack of both a suitable location and the resources required to maintain this superb albeit overly extensive collection (the financial problems were soon aggravated by US spending on the war in Korea). Some of the “artefacts” had to be put up for sale in order to ensure the museum’s upkeep. In consequence, in 1952 the aircraft found its way into the hands of a great aviation enthusiast and collector – Edward “Ed” Maloney. Five years later, the Hayate became the pride of Maloney’s newly established Ontario Air Museum in Chino, California (existing to date as the “Planes of Fame Air Museum”). The fighter was painted green and decorated with fancy stripes of grey paint. The emblem of 102nd Sentai – well known to the Americans from the fighting for Okinawa – was painted on its tail. The camouflage in no way reflected the operational paint scheme of the Ki-84, however “historical accuracy” was not much in vogue at the time. The scheme was supposed to be attractive to viewers, nothing more. Following further repair work in 1963, the aeroplane once again became flyable and drew in crowds of spectators at air shows. Interestingly, the aircraft was most readily presented by the famous P-47 Thunderbolt fighter ace Walker “Bud” Mahurin (flying on the basis of an individual contract).

In the early seventies, Maloney’s business endeavours were faced with a financial crisis. But another war-bird enthusiast and collector, Ed Lykins, came to the rescue. The former white “46” underwent yet another overhaul, and was repainted to boot. This time it received a more or less correct camouflage: green on the upper and side surfaces, and light grey on the underside. The lightning of 11th Sentai (called denko by the pilots) reappeared on its tail, albeit in white, symbolizing affiliation to 1st Chutai. While the new owner enjoyed every moment spent “in the company” of his Hayate, he became more and more convinced that such a valuable object should return to its homeland. In the spring of 1973, he offered to sell the aircraft (for a reasonable price) to the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force (JSDAF). The offer was accepted.

Don Lykins flies Ki-84 during 1973 Japan International Aerospace Show

The Return Home

The aircraft was taken to the JSDAF base in Kisarazu, and on 7 October 1973 it was presented to the general public (and numerous VIPs and the media) both in the air and on the ground during the great air show in Iruma. Incidentally, this was the first flight performed over Japan by an IJAAF fighter since the end of the war. It was flown by Don Lykins, a pilot, actor and stuntman. Although the beginnings of its new life on home soil seemed to herald a great career, time was running out for the Hayate. In the early 1970s, the Japanese were still in complete denial of the “ethos” of the Second World War, and approached the West’s growing interest in the events of 1941–45 with considerable incomprehension (and suspicion). The aeroplane was handed over to Fuji Industries in Utsonomiya (the historical successor to Nakajima), where it was set aside and left to decay. A glimmer of hope appeared 10 years later, when the Hayate came under the loving care of employees of the Arashiyama Museum in Kyoto. Unfortunately, 5 years later the museum fell into disrepair (due to the death of its founder and at once majority donor). Smaller exhibits were sent to various other facilities, while the Ki-84 was left to rot, forgotten.

Ki-84 Hayate No. 1446 in Kamikaze Peace Memorial, 2006. Zdjęcie: Bouquey, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

Ki-84 Hayate No. 1446 in Kamikaze Peace Memorial, 2006. Zdjęcie: Bouquey, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

The final stage in the journey of the white “46” journey began in the mid-nineties, when the last surviving representative of the Ki-84 family was taken over by the Kamikaze Peace Memorial in Chiran (Kagoshima Prefecture). This unique facility, which over the past 50 years has evolved from a sui generis temple to a location commemorating suicide airmen, also houses a collection of memorabilia of pilots from various combat units, and has recently been expanded to include an exhibition of aircraft from the era. Ki-84 serial number 1446 resides there to this day, accompanied by Ki-61 Hien serial number 5070 and a fragment of A6M Zero serial number 62343. It still wears the uniform of 1st Chutai, 11th Sentai – the same (though refreshed) that made its appearance thanks to Ed Lykins.

Following years of neglect on Japanese soil (sic!) it is officially recognized that restoring the aircraft to flying status is completely impossible. But according to my Japanese colleagues, specialists in this field, this is not true. The operation would require immense time and resources, as well as considerable knowledge, however it is “doable”. For the present, the question remains an academic one: taking into account the potential risks to the pilot and the unique artefact itself, no one is seriously contemplating a reactivation of this nature (regardless of the availability of resources, which could doubtless be secured). What is planned is to decorate the aeroplane with the emblem of 2nd Chutai and the white number “46”, probably during the next major renovation of the exhibit.

English translation: Maciek Zakrzewski

See also:

A lover of strong coffee and dark chocolate, incurable optimist, romantic and dreamer, economist by education, historian and modeller by passion. From time immemorial he has been fascinated with aviation in every variety and form. For many years, he has been paying special attention to all aspects of the activities of the Army and Navy Aviation of the Land of the Rising Sun.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski