When discussing the wartime involvement of aeroplanes such as the Hayate, Hayabusa or Zero, we usually focus on the most spectacular aspects: outstanding fighter pilots, famous units, or the most important campaigns conducted in Asia and the Pacific. War, however, is not only about aerial duels. A significant portion of operational activities is accounted for by logistics in the broadest meaning of the term: organizing deliveries of aircraft, spare parts and consumables, training pilots and technical personnel, and transferring these resources to specific locations at strictly defined times. The hero of today’s piece has just such an atypical story to tell.

The Aircraft

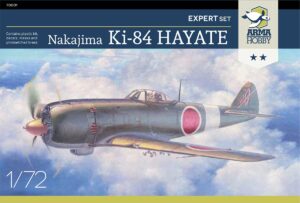

The fighter presented in the illustration was manufactured at the Nakajima plant in Ota towards the end of spring 1944. It had all the characteristic features of the early-series aeroplanes that distinguished it from the prototypes and the initial production batch. Specifically, these were the individual exhaust pipes, a vertical stabilizer and rudder with a smaller (target) surface area, short barrel covers for the fuselage-mounted machine guns, underwing pylons for additional fuel tanks/bombs (instead of the central pylon that had originally been located beneath the fuselage), a windscreen with an armoured plate, a massive headrest (in place of the earlier small armoured plate with a “support”), full wheel hubs for the main landing gear, and a slightly smaller, early version of the oil cooler (used until serial number 2,000). The armament, also typical for the Ki-84 Ko (Ki-84a) version, consisted of two 12.7 mm Ho-103 machine guns in the fuselage and two 20 mm Ho-5 cannons in the wings. The aircraft left the assembly line with the so-called Natural Metal Finish (NMF), i.e. in a natural metal colour.

As I have already mentioned in one of the previous articles, Ota was not just a factory airfield of the Nakajima plant. It was also a large base of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF), housing numerous operational training units resided and logistical facilities responsible for the deployment of new aeroplanes to the front line units.

Ota airbase, photo made just after the cease-fire

Ota airbase, photo made just after the cease-fire

Logistical Channels

A typical practice of the IJAAF in the 1930s was to withdraw individual combat units to Japan in order to refit them with new equipment and personnel. For obvious reasons, this methodology was not optimal (and oftentimes even feasible) in the realities of the ongoing war. To be sure, it was employed, however only when necessitated by circumstances. These included the rebuilding of aerial strength in the wake of serious losses, major reorganizations or, possibly, conversion to completely new aircraft types, combined with the requirement of providing significant additional training for personnel. Whereas deliveries of new (or repaired) equipment to front line Sentais were handled by the Rikugun Koku Yuso (“Army Air Ferry Command”). One of its subordinate units, 2nd Yuso Hikotai (2nd Ferry Squadron), which was operated directly by 3rd Air Army (3 Koku Gun), had its seat at Ota airfield. The command of 3rd Air Army was located in Singapore and was responsible for the operational area of Burma, Siam (Thailand), Malaya, French Indochina and the Dutch East Indies. The central logistical and distribution point in the region was Saigon in Indochina (present-day Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam). The city, surrounded by a chain of airports with a well-developed infrastructure, with a large seaport and situated in a relatively quiet area, was the perfect location from which to conduct the further distribution of military assets. For these reasons, it was a frequent destination for the pilots of 2nd Yuso Hikotai from Ota. One of the many aircraft ferried from Ota to Saigon, the titular Hayate was flown in by Lieutenant Shuho Yamana in the summer of 1944.

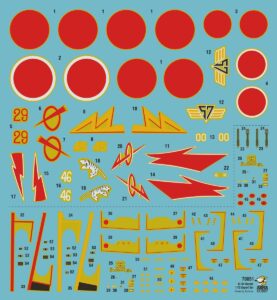

Camouflage and Markings

The presented paint scheme is largely unique (not only in the case of the Ki-84s). Generally speaking, it was a mutation of the field camouflage applied in combat units to aircraft delivered in the Natural Metal Finish. However, these were usually various types of patches, spots or snaking lines created using all and any available green (of very different origin and with a wide range of shades) and/or brown, beige or sallow paints. Here, however, we are dealing with a stencil, sometimes referred to as “Natter” in English-language literature, and for years jokingly called the “green giraffe” by Polish modellers (of course, neither name stems from the Japanese nomenclature of the time). In the case of the titular Hayate, the spotted paint scheme covering the Natural Metal Finish was actually very rare, and only a few Ki-84s wore this “uniform”. Such protective colours were used mainly by the Akeno flight school, and also – albeit sparingly – by 1st and 11th Sentais in Japan (which later took part in the battles for the Philippines). But as regards front line units involved in the fighting of the summer of 1944, only 25th and 50th Sentais, two of the most famous units operating over Burma and China, regularly applied this finish. Even then, however, the camouflage was slightly different. Both units used a paint scheme very similar to the “green giraffe”, which, although appearing more or less the same, was applied in the form irregular patches.

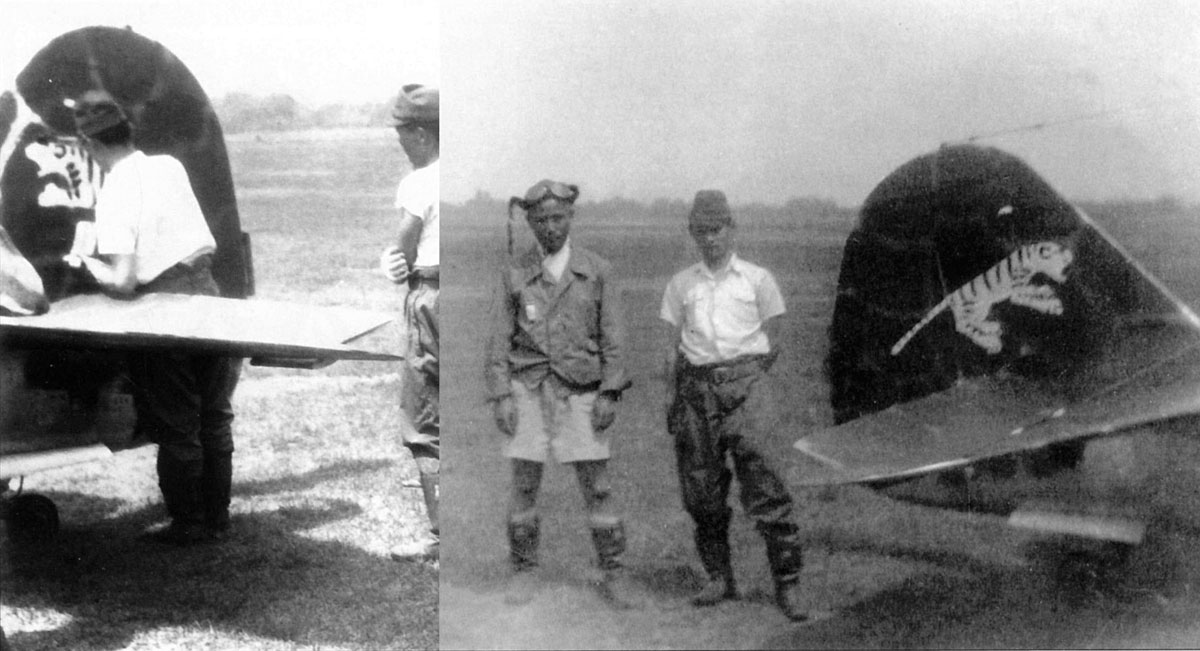

The White Tiger painted by the Lt. Terai under Lt. Yamana’s supervision. Both officers at our Hayate with finished painting. Ota airbase, summer 1944

The White Tiger painted by the Lt. Terai under Lt. Yamana’s supervision. Both officers at our Hayate with finished painting. Ota airbase, summer 1944

The pilots of 2nd Yuso Hikotai were in permanent contact with both units (and with 85th Sentai), as these were usually the recipients of the aircraft delivered to Saigon. The camouflage developed in Ota by the technical crew of 2nd Ferry Squadron was clearly inspired by the “uniforms” used by recipients (although – to be precise – I did not find any data specifically confirming this thesis). The only difference was that the green patterns terminated sharply, while the field camouflage patches had blurred edges. A separate decorative element was the white tiger painted on the tail of this particular machine, which was flown by Lieutenant Yamana. The motif referred to the well-known Chinese saying that “Even if a tiger travels 1,000 miles, it will always return home safe and sound”. The emblem was applied (by hand, without the use of a stencil) by Lieutenant Terai, the Technical Service Chief of 2nd Yuso Hikotai, as a special kind of talisman that would guarantee the safety of both pilot and aircraft. It is worth noting that the Ki-46 Dinahs of 18th Teisatsu Dokuritsu Chutai (18th Independent Reconnaissance Squadron), and later of 82nd Teisatsu Sentai (82nd Reconnaissance Group) carried a similar tiger emblem (although coloured orange and black). Here, too, the symbol referred to the aforementioned Chinese maxim, and was also painted by hand (an important element of the ritual), which resulted in very different visual effects on individual aircraft.

The Pilot

Shuho Yamana, born on 17 June 1920, was one of a generation of young men (not only in Japan) who were absolutely enthralled by aviation. A month after graduating from high school, he enrolled in Yonago Basic Pilot School. Interestingly, the institution was subordinate to the Ministry of Sport. In the autumn of 1939, he completed training with top grades, which ensured that he could enter a military academy. And indeed, in April 1940, he was registered as cadet at the IJAAF Secondary Flight School. Over the next year, he excelled as a student, receiving promotion to second lieutenant and, yet again, earning high grades from his superiors. He immediately applied to join an operational training unit, and then a fighter squadron, however the Army had other plans for him. It was decided that a boy with such high abilities and exceptional piloting skills would make an excellent flight instructor. Thus, Yamana was made an offer which he obviously could not have refused. Over the next few months, he schooled young trainees at the IJAAF Flight School in Kumagaya (Kumagaya Rikugun Hiko Gako). Somewhat by chance, it came to light that Yamana also had a natural talent for navigation – a skill highly uncommon among his contemporaries. The IJAAF’s training program differed fundamentally in this regard from that of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service. For while “navigation” was a subject of instruction as such, the focus was on navigators, bomber crews and long-range reconnaissance. The pilots themselves (and fighter pilots in particular) had a very limited knowledge of the topic; later on in the war, this led to a series of unfortunate and tragic events, which occurred primarily when large tactical units of the IJAAF were sent to distant fronts.

Lt. Yamana at the 11th Sentai airbase after delivery of the next Ki-43 fighter, posing in front of another Hayabusa from this unit. 11th Sentai marking – the lightning – painted in white, colour of the 1st Chutai.

Lt. Yamana at the 11th Sentai airbase after delivery of the next Ki-43 fighter, posing in front of another Hayabusa from this unit. 11th Sentai marking – the lightning – painted in white, colour of the 1st Chutai.

On the eve of war Yamana (now a lieutenant) made a fresh request for assignment to a fighter unit; it was rejected. He was ordered to the Rikugun Koku Yoso. His initial tasks included flying several civilian transport aircraft from the Tachikawa plant to Mukden in Japanese-held Manchuria. Here, however, the term “civilian aeroplane” was purely fictitious. For while the aircraft had civilian registration markings, they were intended for the Transport Corps of the Kwantung Army. In November, Yamana also ferried six Ki-27 Nate fighters for 11th Sentai, which at the time was stationed in Mukden, and then another six to Saigon (from where a few days later the unit attacked Malaya). Following the separation of 2nd Yuso Hikotai in Ota (September 1943), Yamana became the “full-time supplier” of Nakajima fighters to IJAAF logistical centres in Vietnam and China. Occasionally, he would ferry aeroplanes directly to combat units in the CBI (China-Burma-India) Theatre, and in particular to 25th, 50th, 85th and 87th Sentais.

Lt. Yamana smiling at the Taiwan airfield just after return from the dramatic flight to Luzon 23rd January 1945. The White Tiger visible on the nose of the Ki-67 Hiryu bomber

Lt. Yamana smiling at the Taiwan airfield just after return from the dramatic flight to Luzon 23rd January 1945. The White Tiger visible on the nose of the Ki-67 Hiryu bomber

One of his most traumatic experiences was the mission of 23 January 1945. On that day, Yamana was to transport a Ki-67 Hiryu bomber from Japan to Laoag airfield on Luzon. The aircraft was to be used in a bombing mission (or rather a suicide attack) against the American fleet that was then storming the Philippines. But following a failure of the navigation system and radio, the pilot was forced to rely on his own skills along the entire route. He acquitted himself brilliantly. The problem, however, was that during the latter period of the battle for the Philippines the enemy enjoyed complete air superiority over the archipelago. In order to have any chance of survival, the Ki-67 – by no means a light aircraft – had to be flown just above the sea. Taking everything in his stride, Yamana made it safely to Laoag only to discover that the runway had been riddled with bombs. Following a serpentine landing pattern, he pulled of a miracle, although towards the end of the run his right wheel became stuck in one of the craters. Luckily, the aeroplane was quickly rescued. Since, quite obviously, the Sentai was unable to conduct further missions, the pilot embarked the twenty or so surviving members of the unit and began a perilous take-off. At that very moment, a lone PBY Catalina appeared over the airfield and opened fire with its half-inch Brownings (in an interview with Ken Arnold after the war, Yamana noted that although he had been aware of the danger, he was frozen motionless. He stared at the magnificent American flying boat and could not believe that such a beautiful aircraft actually intended to kill him). Although the enemy aeroplane was driven off by anti-aircraft fire, it became crucial to depart without further delay, since American fighters – in all certainty already notified – could arrive at any minute. “Skimming the surface of the ocean”, Yamana managed to make it to Taiwan. Both pilot and ground crews attributed this success to the white tiger that had previously been painted on the bomber’s fuselage just under the cockpit.

Another view of the same Ki-67 with Lt. Yamana’s personal marking

Another view of the same Ki-67 with Lt. Yamana’s personal marking

The lieutenant’s last transport mission was planned to begin at noon on 15 August 1945, and its objective was an IJAAF base in Korea. However, before the brand new and heavily armed Ki-84 Otsu (4 x 20 mm) was prepared for take-off, the Emperor of Japan announced the termination of hostilities.

Epilogue

During his career as a ferry pilot (which lasted almost exactly 4 years), Lieutenant Yamana transported several hundred aircraft of more than twenty different types to logistical centres throughout the continent and directly to front line units. The majority were Nakajima Ki-27 Nate, Ki-43 Hayabusa, Ki-44 Shoki and Ki-84 Hayate fighters, but he also ferried Ki-49 Donryus and Ki-67 Hiryu bombers, and Ki-54 transports and Ki-36 reconnaissance aircraft.

Shortly after the surrender, 25-year-old Yamana changed his name to Kurita (just in case). He took up various jobs, however he still dreamt of flying. Not carrying the stigma of a combat pilot, and at the same time possessing the requisite recommendations from transport aviation, he was optimistic. He was proved right. Shortly after the ban on Japanese aviation was lifted, it became clear that there was a demand for courier, postal, transport and other flights. For some time he worked as a pilot for one of the major Japanese newspapers. Ultimately, however, he completed an international aircraft piloting course (in 1952) and entered employment with Japanese Airlines, where he worked as a Captain Pilot until his retirement in 1979. Over a period of 34 years of service as a pilot (7 years before and during the war and 27 years after the conflict), he flew nearly 4,000 hours with the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force and 19,200 hours with JAL. He spent the final years of his life in the company of his wife, son, daughter-in-law and two grandchildren, devoting himself to his hobby of growing vegetables on a small plot of land near Tokyo.

The further fate of the Hayate with the white tiger on her tail is not well known. It is said that the aircraft was sent to 25th Sentai, however there is no unequivocal proof that this actually occurred, especially as the new Nakajima fighters delivered to Saigon in the summer of 1944 were distributed among three units. In August, 50th Sentai, commanded by Major Tatsujiro Fujii, arrived in Saigon from Burma. A month later, in September, 85th Sentai of Major Togo Saito, which at the time was stationed in Hankou and Canton, was similarly re-equipped. Whereas 25th Sentai, under the command of Major Katsumi Makuidani, moved its aircraft to Hengyang, China, only in early November.

See also:

Zawartość pudełka modelu Ki-84 Hayate 1/72 Expert Set – In-Box

A lover of strong coffee and dark chocolate, incurable optimist, romantic and dreamer, economist by education, historian and modeller by passion. From time immemorial he has been fascinated with aviation in every variety and form. For many years, he has been paying special attention to all aspects of the activities of the Army and Navy Aviation of the Land of the Rising Sun.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski