Belgian Fighter Pilot

Before ending up in the British Isles and flying on the Hurricane, Daniel Albert Raymond Georges le Roy du Vivier – nicknamed “Boy” by his comrades-in-arms – managed to gain some experience as a fighter pilot. In September 1939, while serving with the 2e Régiment d’Aéronautique and defending Belgian neutrality, he clashed in the air with a British Whitley; during the encounter, his Fairey Firefly received several hits. On 14 May 1940, flying the same fighter type (number Y-71), he was actually shot down, and by his own artillery to boot. At that precise moment he could not possibly have described his career as a success, all the more so as Belgium was under occupation, while France, where he had evacuated together with his Groupe “Cocottes”, signed a humiliating truce with Hitler after just a few weeks. Like many other Belgians and Frenchmen, he did the right thing and deserted. He made his way to Britain – the last hope of free men in Europe – by sea, via Gibraltar.

On 9 September 1939, du Vivier underwent his baptism of fire on a Fairey Firefly IIM identical to the one in the photograph. On 14 May 1940, while flying an aircraft with the designation Y-71, he was accidentally shot down by Belgian forces near Antwerp. A photograph of Y-71 can be found on the very interesting website of Daniel Brackx www.belgian-wings.be, from whose collection the above picture has been taken

The Fiat Cr.42 was the primary fighter of Groupe des “Cocottes” at the time of the German invasion on 10 May 1940. As many as seventeen of the twenty-seven that were in service were destroyed or badly damaged on the airfields of Brustem and Nivelles during the first day of the Third Reich’s attack. The unit was forced to pull its old Fireflies out of storage. Photograph by Daniel Brackx

RAF and first victories

Arriving in Liverpool on 7 July, du Vivier was immediately sent to 7 OTU (No. 7 Operational Training Unit RAF), where he proceeded to train on the Hurricane. Already on 5 August 1940, he was posted to No. 43 Squadron RAF stationed at Tangmere. He made his first operational flight on 9 August, and débuted in combat against the Luftwaffe four days later, on 13 August, when his squadron reported shooting down two German bombers and damaging one. There were aerial battles almost daily, and on 16 August du Vivier scored his first victory, a Junkers 87 – one of the seventeen kills claimed that day by the “Fighting Cocks”. His luck ran out on 2 September, when during a dogfight with a Bf 109 his Hurricane (P3903) was hit and he was wounded in the leg, and had to save himself by jumping with a parachute. The injury forced him to take a longer break from flying. He returned to his unit only on 5 October; interestingly, a month prior, on 8 September, the squadron had been withdrawn for rest to Unsworth in Northern England, thereby ending its participation in the Battle of Britain.

The claim that resurfaces from time to time, namely that in September 1940 du Vivier served with No. 229 Squadron RAF and scored two probable victories, over a Ju 88 and an Me 109, is false. In fact, there was a British pilot of the same surname, P/O Reginald Albert Lloyd du Vivier, who also fought in the Battle of Britain with No. 229 Squadron RAF and perished in Hurricane W9307 on 30 March 1941.

No. 43 Squadron RAF spent the autumn months training the new pilots who had been drafted in as replacements for the casualties suffered during the three previous months of front line service. At the same time, a number of operational flights were carried out; these were concerned mainly with intercepting reconnaissance aircraft. Among the pilots with whom du Vivier met on a daily basis were P/O Frank Carey, whom I mentioned while recounting the adventures of the Australian ace “Jack” Storey, and P/O Andrzej Malarowski, whom you can also read about in my earlier article.

Stationed from mid-December 1940 at Drem in Scotland, the pilots did not have many opportunities to fight. It must have been all the more disappointing for du Vivier that, when on 9 April 1941, flying in a pair with Sgt Scorer, he finally got a chance, it turned out that the two pilots had spent their entire ammunition, and the Junkers 88 with which they caught up ultimately got away.

On 14 April 1941, du Vivier was promoted to Flight Lieutenant and took command of A Flight. The unit soon received its first Hurricanes – Mk.IIBs – and commenced night patrols; these proved fairly effective, as it gained three victories on the night of 5/6 May, and a few more the following night. Before dusk on 7 May, when du Vivier was flying with a trainee pilot, another Junkers 88 was added to the squadron’s kill tally. The situation repeated itself on 10 May, when a planned training flight became an operational flight upon detection of an enemy aircraft. Once again, the pair of pilots quickly dealt with the Junkers 88, which fell into the sea. The Belgian shared these victories with his wingmen. On 28 May, du Vivier dispatched yet another Junkers bomber, this one on a reconnaissance mission. While intercepting the intruder, his wingman, P/O Franciszek Czajkowski, began to lose oil and had to withdraw from the pursuit, thus granting the Belgian a full “kill”. May 1941 was without doubt a turning point in the Belgian fighter pilot’s career. He was finally able to forget his previous failures.

Photo: Daniel Brackx

Success brought with it medals and awards. On 21 July 1941, the Belgian National Day, du Vivier received the Belgian Croix de Guerre, followed by the Distinguished Flying Cross in January 1942. The justification for the award cited his excellent conduct in a critical situation in which the squadron’s commander, S/Ldr Thomas Frederick Dalton-Morgan, had found himself. Namely, while flying in a pair with P/O David Bourne, Dalton-Morgan had experienced an engine failure; nevertheless, he still managed to catch up with a Junkers 88, attack it a number of times and, together with his wingman, shoot it down. Moments later, his faulty engine – previously forced into combat – gave up the ghost and the pilot had to splash down. Du Vivier took off immediately, relieved Bourne, who had been circling over the survivor and was by then running out of fuel, and guided the destroyer HMS Ludow to the location of his commander’s dinghy. Following this adventure, Dalton-Morgan went on leave, and during this time du Vivier took temporary command of the unit, which at the time did not have operational status.

In No. 43. Squadron’s command

Six months later, in January 1942, he replaced Dalton-Morgan on a permanent basis as commander of No. 43 Squadron RAF. S/Ldr du Vivier was the first non-British pilot to assume command of a British squadron. His personal aircraft was the Hurricane Mk.IIC BN230.

The Hurricane BN230/FT-A was decorated with two crossed flags – the Belgian and the RAF Ensign, and the black and white “taxi” stripe used by No. 43 Squadron RAF since the 1920s. Today, you can see the aircraft’s paint scheme recreated on LF751 at The Spitfire & Hurricane Memorial Museum in Ramsgate near Manston, as well as the sheet metal plate visible in the photograph above, upon which du Vivier’s personal markings were painted. Photograph by Daniel Brackx

On 25 April 1942, a section of three Hurricanes led by du Vivier was scrambled to intercept an intruder over the North Sea, and found a lone Ju 88 at 29,000 feet (approximately 8,800 metres). The German pilot tried to save himself by diving, and his gunner managed to hit the Belgian’s aeroplane. One of the bullets pierced the Hurricane’s windscreen and shattered into pieces against the armour plating behind the pilot, wounding him superficially in the face. In response, du Vivier fired several short cannon bursts towards the Junkers – which was diving with great speed – from a distance of approximately 400 yards, and saw his victim hit the surface of the water without undertaking any further evasive manoeuvres.

The unit commanded by the Belgian was stationed at Drem in Scotland and Acklington in Northern England for a considerable length of time, playing a somewhat special role in the RAF’s training system. It was realised that immediately after completing an OTU course the majority of Allied aviators were not capable of engaging in combat on an equal footing with the experienced Luftwaffe pilots. The RAF’s No. 13 Group, of which No. 43 Squadron then formed a part, provided such pilots with a form of combat traineeship at locations where the risk of encountering Messerschmitts or Focke-Wulfs operated by Experten was practically non-existent. At the same time, these rookies were regularly accompanied by experienced veterans such as Carey, Dalton-Morgan or du Vivier himself, from whom they adopted habits that increased their chances of survival. The more talented young fighters would have their stays with No. 43 Squadron RAF extended. This method of selection allowed it to become probably one of the best-trained RAF units of the time, while Le Roy du Vivier proved himself as a mentor.

Another distinctive feature was the unit’s highly international composition. Almost ninety novice pilots, hailing from sixteen different countries, passed through No. 43 Squadron RAF.

A photograph of pilots of different nationalities standing in front of Hurricane Mk.IIa Z2641/FT-R “URUNDI”. First on the left is P/O Andrzej Malarowski, who served with No. 43 Squadron RAF until March 1941. Photograph from the collection of Piotr Sikora

This role of the unit, combining pilot training with limited combat activity, was continued until mid-June 1942, when it returned – after almost two years – to Tangmere, relieving No. 1 Squadron RAF prior to its planned re-equipment with the Hawker Typhoon. The “Fighting Cocks” also took over the intruder duties of their predecessors. In preparation for their new task, the rest of the month was devoted to training in attacking ground targets, which undoubtedly proved useful during the upcoming raid on Dieppe.

While it was stationed at Tangmere, the unit took part in Operation Jubilee, on 19 August 1942; this action will be described in a separate article. Du Vivier’s four missions that day, the first flown on BN230/FT-A and next three on Z3081/FT-V, as well as his outstanding command of the unit, led to his second award of the DFC in September 1942.

On 14 September 1942, S/Ldr du Vivier bid farewell to the “Fighting Cocks” and thus also to the Hurricane fighter. During the more than two years that he operated the Hurricane, he became a consummate fighter pilot, an excellent commander and a capable instructor, making a permanent contribution to Belgian and British aviation history.

Du Vivier’s Hurricane

Hurricane Mk.IIc Z3081/FT-V “Baron Dhanis”. No. 43 Squadron RAF. Tangmere airfield. Three missions in operation “Jubilee”. Pilot S/Ldr D.A.R.G. Le Roy du Vivier (Belgium)

The films held by the Imperial War Museum allowed us to recreate the appearance of another of du Vivier’s aircraft – not the commonly known BN230/FT-A.

By the time it was filmed with S/Ldr du Vivier at the controls, Z3081 had already seen extended service. In July 1941, it was operated by No. 242 Squadron RAF, while in mid-September it was passed on to No. 615 Squadron RAF. On 27 October, during an attack on a seaplane base in Ostend, it was hit by anti-aircraft artillery, and its wounded pilot, P/O C. G. Ford, subsequently struggled to make a successful belly-landing at Manston. Following repairs, the aeroplane was sent to No. 43 Squadron RAF in June 1942. At the time, it carried the code letters FT-C. The letter C was painted over somewhat carelessly and shone through from beneath the black paint – more clearly on the right. It was not technically possible to render this in a decal, and we therefore leave the detail to be done by the discerning modeller himself, based on the photographs. In addition, the aircraft was covered almost entirely in black night camouflage, with the exception of the upper right side of the antenna mast. It bore its own name, “Baron Dhanis”, in honour of the commander of the armed forces of Congo Free State, Francis Dhanis, who crushed the Arab slave traders in 1894. All the names inscribed on the aircraft of No. 43 Squadron RAF from the end of July 1942 onwards were related to the Belgian Congo and were primarily those of cities or of people associated with the colony’s history.

Tangmere, 19 August 1942, 7:50 am. The squadron’s second task of the day and du Vivier’s first on Z3081. The rectangle under the code letter stands out slightly. A trace of the painting over of the previous marking. Photo: still from film ARY 17-4 0745 – Imperial War Museum collection

Tangmere, 19 August 1942, 1:45 pm. Taking off for the final task of Operation Jubilee. S/Ldr du Vivier was paired with Sgt W. Webster, a New Zealander, who flew on Hurricane Mk.IIb AM315/X “Tabora”. In the photograph, only the lower part of the antenna mast of Z3081 is painted black. The old code letter, “C”, can be seen shining through the thin layer of black paint. Photo: still from film ARY 17-4 0745 – Imperial War Museum collection

Hurricane Mk.IIb (built by CC&F as Mk.X) AM315/FT-X „Tabora”. No. 43 Squadron RAF. Tangmere airfield. Aeroplane took part in four missions during operation „Jubilee”. Pilots: F/Sgt J.D. Lewis, P/O R. Turkington, Sgt M. Smith, Sgt W. Webster (RNZAF)

Sources:

- No. 43 Squadron: Operations Record Book AIR 27/441–443

- No. 229 Squadron: Operations Record Book AIR 27/1418

- Andy Saunders “No. 43 Squadron ”Fighting Cocks” Squadron”, Osprey Publishing.

- Jimmy Beedle “The Fighting Cocks: 43 (Fighter) Squadron”.

- Jean Buzin “Daniel Le Roy du Vivier 1915–1981” https://www.vieillestiges.be/files/biographies/BioLeRoyduVivierFR.pdf

- Norman Franks “RAF Fighter Command Losses of the Second World War”.

- Photographs from the collection of Daniel Brackx https://www.belgian-wings.be/

Translation: Maciek Zakrzewski

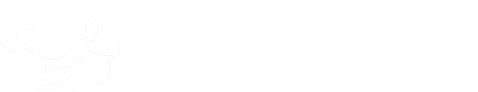

Jubilee Anniversary Promotion!

On this occasion, for modellers, we have prepared a special, jam-packed anniversary model kit – Hurricane IIC “Jubilee” in 1/48 scale.

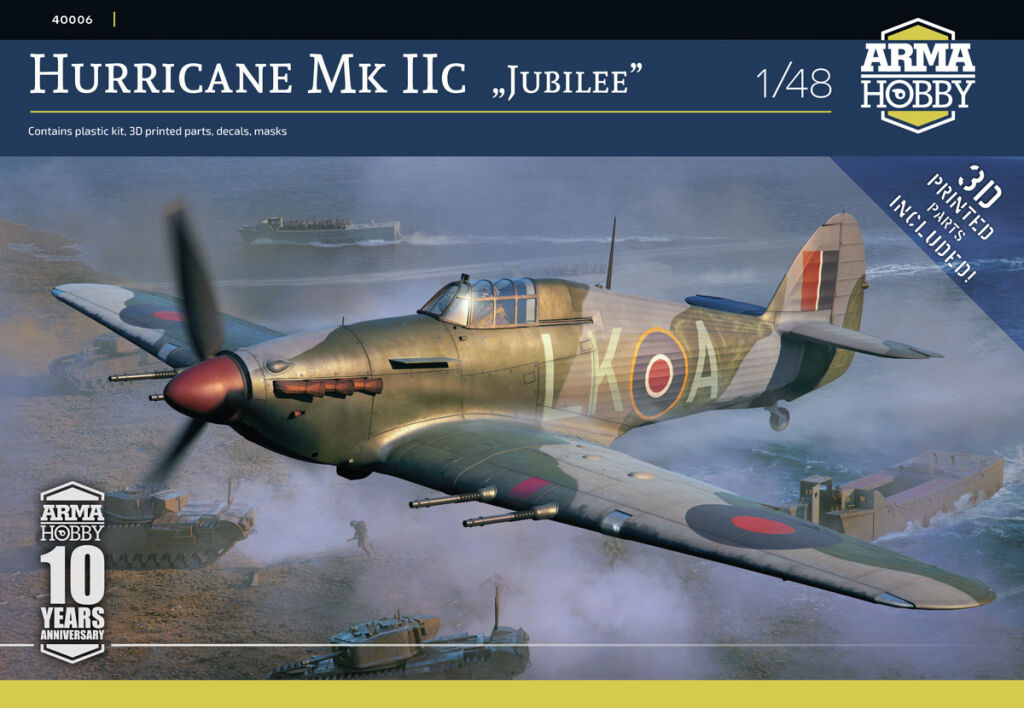

This is a set with marking schemes from Operation “Jubilee” – the Allied Dieppe landing, with a box filled with a full set of 3D-printed resin accessories. This unique kit is released in a small, limited series for the 10th anniversary of Arma Hobby and will not be reissued!

Promotion lasts from 2nd to 15th November. Other Arma Hobby 1/48 kits have special discounts during this period.

We are preparing an anniversary offer for 1/72 modellers from November 16, please be patient.

Go to Armahobby.com online store and check the Anniversary model kit:

Model maker for 45 years, now rather a theoretician, collector and conceptual modeller. Brought up on Matchbox kits and reading "303 Squadron" book. An admirer of the works of Roy Huxley and Sydney Camm.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski