He was marvellous at aerobatics. As I watched him climb and roll in the sunlight, I thought I was looking at a swimmer revelling in the warm water of a clear lake. A slow roll to the right, and the ripples flowed down from the body of the plane, the billowing air caressed him and stroked the tips of his wings. Another dive in silence, and then the happy sound of the engine throbbing gently in the calm air.

This awestruck description of R.R.S.T.’s piloting skills was written by P/O Geoffrey Myers, the Intelligence Officer assigned to No. 257 Squadron RAF. R.R.S.T. definitely felt one with the element of air – and with the aeroplanes which he flew. Five years of service with the RAF and several months spent in constant combat had honed his piloting technique to perfection. Such is the story of “Immortal Tuck” – a man who in the months of the Battle of Britain quickly grew into a legend, readily embellished with successive chapters.

Youth and beginnings in aviation

Due to his extraordinary liveliness, Robert found school difficult. He was a successful athlete, and excelled in shooting, but found study less enticing and did not want to follow in the footsteps of his father and older brother, who were both businessmen. At the age of 17, he signed on the steamship SS “Marconi”, on which he spent the next two and a half years, transporting mainly frozen meat from Argentina. But acting on impulse, without much thought, he abandoned his well-started career in the merchant marine. He recalled seeing a newspaper advertisement encouraging young men to join the Royal Air Force; after a few weeks, he was already qualified for the training, which he commenced in September 1935 at No. 3 Flying Training School, while his first flight – as a passenger – took place on an Avro Tutor K3257. Two events could have ended his flying career prematurely. The first was an initial problem with understanding the rules of piloting, but eventually, after 13 hours of flights with an instructor, he made a correct flight himself and from then on coped excellently with the study of flying. The second was a juvenile stunt when, drunk, he, along with his friend Malcolm John Loudon, participated in a car crash and was threatened with disciplinary dismissal from the armed forces. He was saved by the intercession of the school commander, an ace of the Great War, William Staton, who refused to cross off two talented young fighter pilots. After these adventures, on 20 August 1936 he reported for duty at No. 65 (East India) Squadron RAF, which had just received the single-seat Gloster Gauntlet. Less than a year later, in June 1937, the Gauntlets were replaced with Gladiators. These aircraft are associated with one very important event in the aviation career of R.R.S.T. On 17 January 1938, three pilots took part in formation flight training; tragically, Sgt Geoffrey E. Gaskell momentarily lost control of his Gladiator K8014, colliding with R.R.S.T. on K7940. Sgt Gaskell perished, while R.R.S.T., following a struggle with the cockpit canopy, jumped to safety, opening his parachute at 300 feet (less than 100 m). He carried lifelong reminders of the catastrophe – a long scar on the right side of his face and a slight limp. The scar led him to grow his characteristic moustache, which was intended to cover the trace.

War!

In March 1939, No. 65 Squadron RAF was rearmed with the Spitfire. Following the outbreak of the war, the unit was stationed at Hornchurch and Northolt, near London, and did not take part in the battles over France. Although R.R.S.T. flew on many different Spitfires, he most often operated aeroplane K9908, marked with the letters FZ-M (and YT-M from September 1939, when the code letters were changed).

In May 1940, R.R.S.T. was transferred to No. 92 Squadron RAF, also known as “East India”, and promoted to the rank of Flight Lieutenant. With this unit, he experienced his baptism of fire and scored his first victories. As a matter of fact, becoming a fighter ace took him less than a day. On 23 May 1940 before noon, he shot down a Bf 109, followed by two Bf 110s in the afternoon, while the next morning he added two Dorniers to his tally – and received his first war wound, albeit so inconsequential that it did not interfere with his military service. It has been determined that he scored his first victories on 23 May flying on N3192/GR-L. Numerous dogfights and kills later, on 11 June 1940, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. But there were also setbacks. On 15 July, he became disoriented in bad weather and had to land in a chance area, damaging his propeller. On 18 August, he was shot down by Ju 88 – which he nevertheless managed to shoot down. R.R.S.T. parachuted to safety. But on 25 August the situation repeated itself, as his Spitfire was once again shot down by the gunner of an already mortally hit bomber. He managed to land immediately after crossing the coastline, however after a hard touchdown R.R.S.T. was taken to hospital, while his fighter was scrapped. This was also his last flight with No. 92 Squadron RAF, with which he achieved eleven confirmed individual kills and reported two probables. Interestingly, Tuck kept his own statistics, and according to these the list was slightly longer; accordingly, after arriving at No. 257 Squadron RAF, he ordered a row of fourteen swastikas to be painted on his aircraft.

No. 257 „Burma” Squadron

Initially, No. 257 Squadron RAF had operated flying boats, and was disbanded in mid-1919. It was re-formed on 17 May 1940 as a fighter unit armed with the Spitfire. Most of its pilots had recently received training at Operational Training Units of the RAF and possessed no combat experience. Its commander, S/Ldr David Walter Bayne, who, like his friend Douglas Bader, had lost a leg in an accident involving the Bristol Bulldog, was one of the few experienced pilots and tried to turn his young pilots into a close-knit team. The obstacles were numerous. Already on 10 June 1940, pilots who were in the course of intense training on the Spitfire learned that starting from the next day they would fly the Hurricane. This was due to the losses which the RAF had suffered during Operation Dynamo. Providing cover for the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force had cost the RAF more than forty Spitfires (all irretrievably lost), and so the aircraft of No. 257 Squadron and two other units were used to supplement the numbers of the squadrons which had been mauled over Dunkirk. However, refitting did not lead to any postponement of attainment of operational status, and the squadron commenced combat flights on 1 July 1940. Another significant event occurred on 22 July 1940, when S/Ldr Bayne was transferred to the Headquarters of Fighter Command at Bentley Priory. S/Ldr Hill Harkness became the unit’s new commander. This change had a much more adverse effect than the switch from Spitfire to Hurricane. Harkness proved to be an extremely incompetent superior. Previously, he had served with a training unit, and had neither the talent nor the experience to lead a front line unit. Furthermore, his personality made cooperation difficult. In August, five pilots were killed and three injured, while equipment losses equalled the number of claimed victories. When Harkness was forced to command in the air, he tried to avoid combat, or, through his inept decisions, placed his subordinates at the mercy of the Messerschmitts. Morale was extremely low, especially as the pilots regularly read the propagandistic descriptions of the numerous victories purportedly scored by other squadrons and compared them to the tragic balance of their own efforts. The fighting of 7 September 1940, when two of the unit’s most experienced pilots, flight commanders F/Lt Hugh R. A. Beresford and F/O Lancelot R. G. Mitchell were killed, left an indelible mark. Soon, they were replaced by new airmen: F/Lt Peter Malam Brothers and F/Lt Robert Stanford Tuck.

R.R.S.T. with No. 257 Squadron

R.R.S.T. arrived in Martlesham, where the squadron was stationed, on 11 September. Tellingly, he needed only a few hours to figure out the reasons for the unit’s tragic situation. The next day, after a few drinks to raise his courage, he called Keith Park – the commander of the RAF’s No. 11 Group – himself, with the result that Harkness was removed from his post with immediate effect and the squadron handed over to R.R.S.T. Harkness was sent to Canada and probably failed there too, for he resigned from service in December 1943.

At the time of his promotion to Squadron Leader, R.R.S.T. was already a hero, an ace with more than ten victories and immense experience.

Cuthbert Orde painting/Public Domain

The biography “Fly to your life” contains a description of the impression he might have made on the pilots of No. 257 Squadron RAF during their first meeting:

To them he seemed a lean, mean and vainglorious person. He had a dry, arrogant face and he walked with his head held high, like a blind man. The immaculate uniform, the glossy hair and the “Cesar Romero” moustache kindled their instinctive scorn for all forms of bull-shine. It was true that, outwardly, he often seemed a noisy show-off and a bit of a fop, too. Lately, he had taken to using a long, slim cigarette holder and his mannerism were very haughty indeed!

However, what he looked like on the ground had little to do with what he was like in the air, and his subordinates had to notice and appreciate it right away.

The new squadron leader demanded that No. 11 Group give him a few days for “quick” pilot training in current air combat principles. R.R.S.T. taught his charges the basics of aerial fighting in pairs, which had initially been developed by the Luftwaffe, whose pilots flew in a loose formation that ensured better conditions for observing space and greater freedom of manoeuvre. And, what was equally important, he passed on to them his enthusiasm, his will to fight and his belief that they could be effective warriors, provided they were properly commanded. He probably also won their sympathy during evening pub visits, where he stood a good few rounds, building trust and camaraderie as only he knew how. By all means, he was a commander who impressed with his achievements – not only an appointee, but a man who possessed the authority and the qualities of one for whom young boys would go through fire and water.

The pilots of No. 257 Squadron RAF and the unit’s new commander passed their exam on 15 September, when the Battle of Britain was at its climax. Facing massive pressure from the Luftwaffe, command was forced to send the squadron to battle while still insufficiently prepared. However, luck favoured R.R.S.T., and that day his pilots, despite intense clashes, suffered no losses (with the exception of damage to several aeroplanes), while reporting five victories. That day, R.R.S.T. destroyed one Bf 110 and claimed one Bf 109.

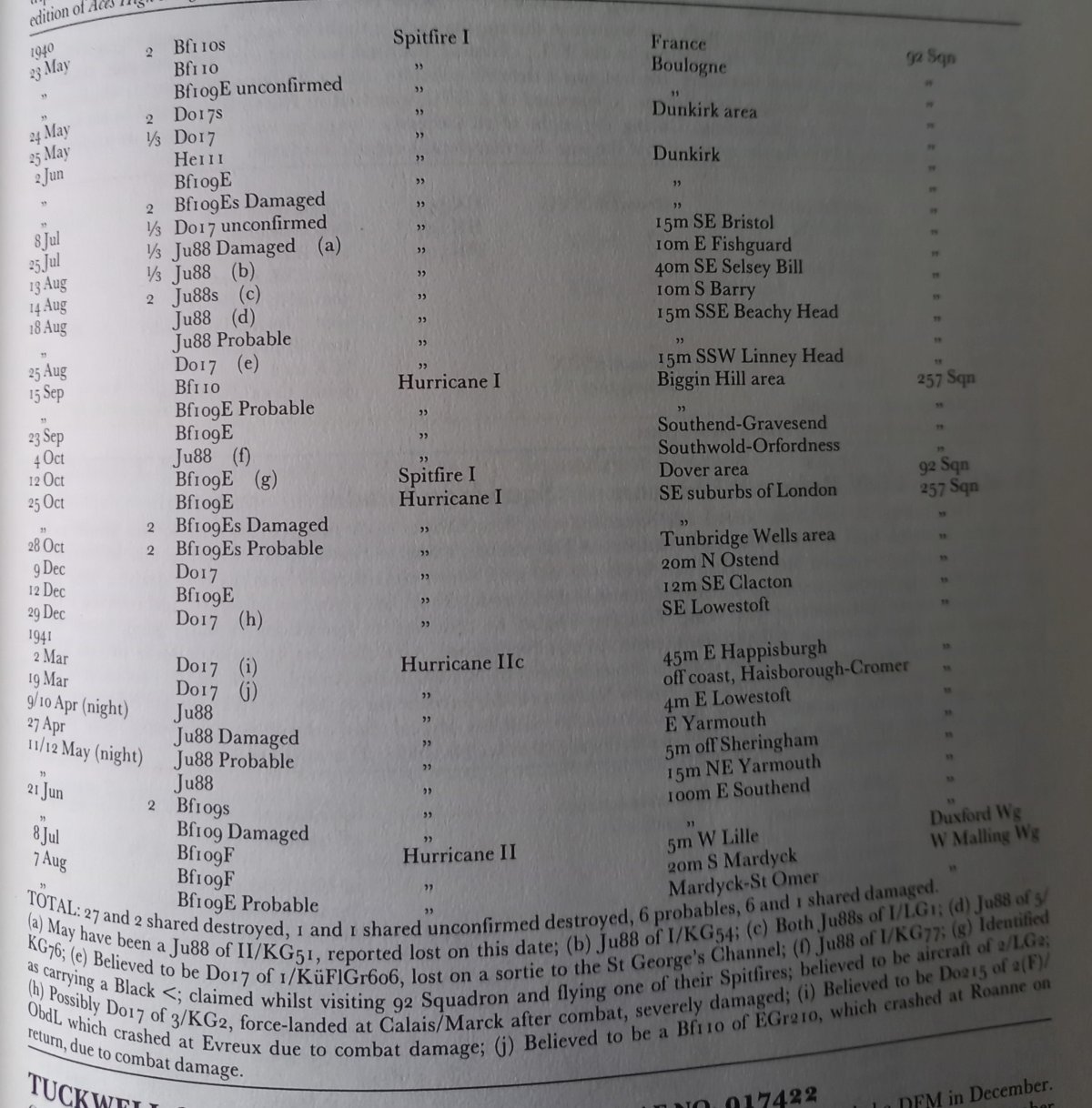

After such a successful day, the pilots drove off to celebrate in the local pubs. As it turned out, 15 September was not only a turning point in the struggle with the Luftwaffe, but also marked the beginning of a new era for the entire No. 257 Squadron RAF, under new leadership. Thus, they observed the moment joyously, and began their way back to quarters in a carefree mood. Unfortunately, the car driven by R.R.S.T. hit the back of the vehicle carrying other airmen and Intelligence Officer Myers. In consequence, two pilots who had hitherto successfully fought against all adversities of fate were seriously injured through the carelessness of their commander and thus eliminated from service for many months. Even though the staid Myers was a victim of the accident, he was impressed from the beginning by Tuck’s leadership style and his human management skills, he was not entirely uncritical. Soon, as a professional, he also began to ponder over the consistency of the reports that R.R.S.T. submitted regarding his combat fights. In one instance, he checked the conformity of Tuck’s report with the actual combat usage of ammunition. According to the document, R.R.S.T. fired a total of several bursts lasting eleven seconds in total, but only 480 rounds were in fact fired, which should have lasted three seconds at most. On the basis of documents available today, we may conclude that Tuck’s depiction of his solitary fight with a Do 17Z on 2 March 1941, which according to him splashed down, was not fully accurate. The aircraft which according to Christopher Shores’ “Aces high” could have been the victim of the attack, flew on to Evreaux, some 100 km from the English Channel coastline. The same goes for R.R.S.T.’s solitary combat of 19 March 1941, regarding which he claimed that the enemy aeroplane, a Dornier, fell into the sea near Haisborough Sands, while Shores credits the pilot with downing a Bf 110 some 800 km to the south, near Lyon. This analysis of the circumstances in which Tuck scored his victories indicates that Myers could have had reason to doubt the veracity of at least certain of his successes. All of the victories that R.R.S.T. claimed between 9 December 1940 and 21 June 1941 were achieved in solo flights, and, had they not been reported by Tuck himself, without gun camera footage or at least witness confirmation, they would probably not have been accepted.

Despite these doubts, there was no question that R.R.S.T. was the best that could have happened to No. 257 Squadron RAF. Command recognized his talents – both those displayed in combat and those which allowed him to lead effectively – and rewarded him again with the Distinguished Flying Cross (and Bar) in October 1940, and with the Distinguished Flying Cross and Two Bars in March 1941. In January 1941, he received the Distinguished Service Order.

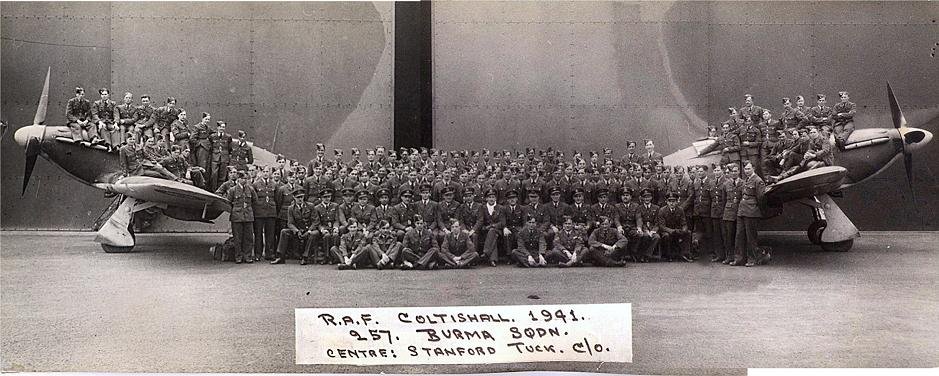

Memorial photo made on 17 May 1941 at No. 257 Squadron anniversary.

New weapon: Hurricane with cannons

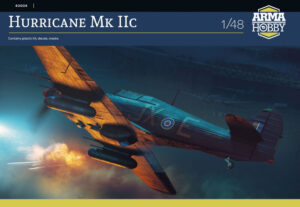

In April 1941, the squadron became one of the first units to be re-equipped with the Hurricane Mk.IIC, which was armed with four HS.404 wing-mounted cannons. R.R.S.T. had in fact criticized the insufficient stopping power of the Browning 0.303 machine guns ever since his first clashes with German bombers, and, unlike Douglas Bader, demanded that the decision-makers quickly introduce fighters armed with 20 mm cannons. He had an opportunity to observe the first trials of the HS.404 while serving with No. 65 Squadron RAF, and wanted to have the weapon in his hands as soon as possible. Tuck made his first flight on Z3152/FM-A on 17 April, and used the aircraft as his primary combat tool until 21 June, when, while shooting down two Bf 109s and damaging a third, it received such serious damage that he was forced to parachute over the sea. Earlier, on 12 May, just after midnight, he had scored on confirmed victory and one probable – both against Ju 88s – on the fighter. In his post-flight report, he stated that after his fifth burst the Junkers’ right wing fell off at the engine and almost hit his Hurricane. He could certainly have thought that his complaints about the fighter’s weaponry had been heard out, and that he now commanded a very powerful aircraft, capable of settling the fight with rapidity and decisiveness. However, while the Hurricane Mk.IIC excelled in combatting bombers, when the squadron began to offensive operations over France, where it encountered the rather fast Messerschmitt, the British cannon-armed aircraft, crippled by its greater weight and inferior performance, proved to be considerably less effective; in consequence, in the summer of 1941 No. 257 Squadron RAF used only the Mk.IIB version.

R.R.S.T., promoted to Wing Commander, took over command of the Duxford Wing in early July.

Trip across the Atlantic in 1941 with “Sailor” Malan. R.R.S.T. was not Heavy Metal fan, this gesture at his times meant having fun. Photo: still from film MGH 3574 in Imperial War Museum collections – used under the right to quote

In October, together with another famous ace, “Sailor” Malan, he was sent to the USA, where he familiarized himself with the numerous new American fighter types: the P-43, P-40, P-38, P-39, P-51, and the P-47 prototype. At the same time, he taught modern air combat tactics to American fighter pilots.

R.R.S.T. flew many hours on the P-43 Lancer in the USA, including forced landing in the countryside. Photo shows Lancer with “Sailor” Malan in the cockpit. Photo: still from film MGH 3574 in Imperial War Museum collections – used under the right to quote

In mid-December, after returning home, he became commander of the Biggin Hill Wing.

The last sortie

On 28 January 1942, flying a Spitfire, he made his last operational wartime flight. Hit by flak, he was forced crash land and taken prisoner. But before being sent to the POW camp, he was invited by German fliers to Saint Omer airfield, where he was hosted by Adolf Galland. This was their first meeting – not counting those which may have occurred in the air, in altogether more hostile circumstances. The next, but not the last, took place after the war, when R.R.S.T. participated in interrogations of captured German pilots.

His visit to Saint Omer marked the beginning not only of a friendly relationship with Galland, but also of a three-year period of captivity. R.R.S.T. ended up at Stalag Luft III, where he was reunited with dozens of long-unseen comrades in arms. Many of them went on to take part in the famous Great Escape in March 1944, and, recaptured, were murdered by the Germans. Among the victims were his friend and the first commander of No. 92 Squadron RAF, Roger Joyce Bushell, whose flying career ended on 23 May 1940, on the very same day when Tuck scored his first kill. R.R.S.T. did not take part in the breakout, because he had been transferred to another, heavily guarded camp. In the winter of 1945, with the German defences collapsing all around, an attempt was made to evacuate the prisoners. The marching prisoners, utterly exhausted, were guarded with steadily decreasing attention by equally tired German soldiers, and R.R.S.T., teaming up with a Polish colleague, F/Lt Zbigniew Kustrzyński, managed to flee and hide until the arrival of Soviet troops. Passing through Moscow and Odessa, they arrived by ship in Naples, there they boarded the transport “Warwick” to Lyneham, England, arriving at their destination on 3 April 1945. R.R.S.T. did not return to combat before the end of the war. He was sent to refresher course, where he flew with an instructor on a Harvard. Soon, he joined the Central Fighter Establishment as a pilot, testing various British fighter jets, including the Meteor, while at the same time commanding fighter units at RAF Hethel and Coltishall. He retired from active service with the RAF on 13 May 1949 as a Wing Commander. Interestingly, the English Electric Canberra, with whose development he would be involved as a test pilot employed by the English Electric Group, was test flown on the same day. It was on this aeroplane that Tuck ended his career. On 20 February 1953, he was a crewman of the Canberra WE135, which, after a long flight lasting more than four hours, landed at the English Electric factory airfield at Warton. This was the last entry in his logbook.

R.R.S.Tuck’s table of combat victories from Christopher Shores’ book Aces High

In later years, he maintained some form of contact with aviation. Together with the aces Douglas Bader, Peter Townsend, Johnnie Johnson and James Lacey, he was invited to participate in various aviation-related events. In the late 1960s, working as a consultant, he participated along with a group of veterans in the production of the film “Battle of Britain”, where he met up again with Adolf Galland. The gentlemen took a liking to each other, and their friendship lasted until Robert Ronald Stanford Tuck’s death on 5 May 1987.

R.R.S.T.’s Hurricanes in modeller’s eye

Arma Hobby’s paint schemes and decals were based on two of R.R.S.T.’s personal aircraft. The first was Mk.I V6864, and the second Mk.IIC Z3152. While V6864 boasts of plenty of footage and numerous photographs from early January 1941, Z3152’s appearance has been reconstructed from four photographs taken in May 1941, which are presently held by the Imperial War Museum. Unfortunately, they all show the aeroplane from the right; thus, how the left side looked – whether it had 28 or more than 30 swastikas – will forever remain a mystery. Due to the fact that R.R.S.T. made his first flight on Z3152 on 17 April 1941, that is, after the uniform painting of monoplane undersides was reinstated, we have not proposed that the left wing be painted black. Nevertheless, we have managed to determine that Z3152’s propeller spinner was not painted in a non-standard red – which some researchers have maintained. Thus, discussions about whether the aeroplane had a white-and-red spinner, or perhaps painted in Sky with a red frontal part, are now moot.

Our reconstruction of the Z3152 was based on photos from the IWM collection. Unfortunately, there is no photo of the port side of the aircraft and its appearance, mainly the way of victory markings, is based on V6864, the aircraft used immediately before Z3152. Certainly, however, the plane was painted in a regulations manner, with markings and identification elements typical of that period. Nor was she wearing a red spinner.

Photos of the FM-A Z3152 Hurricane can be seen on the Imperial War Museum website:

But this gave rise to the following question: Why was this unique marking not transferred to the squadron leader’s new aircraft?

I will venture to say that this was not done because none of R.R.S.T.’s aircraft ever had a red spinner. Although we do not know who or when first interpreted the black-and-white photographs in this way, but I myself see only a peeling layer of Sky paint which reveals the original black base, and not a carefully painted red spinner. Problems with the durability of paint coatings on black spinners afflicted not only V6864. After reading his biography, the fact that R.R.S.T. never denied this – and he had to have seen numerous coloured silhouettes and models presenting his fighter – does not surprise me in the slightest. A man who attached so much importance to his own appearance that he ordered uniforms (and indeed battle-dresses) from Savile Row tailors could easily have appreciated a decorative element that was added to his aeroplane after the war. With this slightly humorous remark, I leave my readers to conduct their own analysis and interpretation of the photographs.

What catches the eye in the photos and the video below from British Pathé is the irregular colour border between the colours on the spinner and the non-uniform surface of the front part of the spinner. This does not appear to be a carefully painted individual marking, but the problem arose from the Sky paint peeling off the spinner ashortly before the photo was done. The problem with the durability of the paint coating was not only on the R.R.S.T. plane, in the third photo in the background and in the fourth photo you can see another machine with a dark front of the spinner.

Author would like to thank John Englested and Grzegorz Mazurowski for help in preparation of this article.

Bibliography:

- Larry Forrester. Fly For Your Life: The Story of Spitfire & Hurricane Ace Robert Stanford Tuck

- John Willis. Secret Letters: A Battle of Britain Love Story

- R.R.S.T. Pilot’s Flying Log

- Christopher Shores. Aces High

See also:

Model maker for 45 years, now rather a theoretician, collector and conceptual modeller. Brought up on Matchbox kits and reading "303 Squadron" book. An admirer of the works of Roy Huxley and Sydney Camm.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski

I was of the impression his name was Robert “Roland” Stanford Tuck (not Ronald) having read the unabridged version of his biography back in the 60’s. He spent a couple of years in the merchant navy where he sharpened his aim and deflection skills shooting sharks with a .303 rifle …

I already have a couple of ARMA’s Hurricanes in 1/72 including the markings of Tuck DToA. that being my preferred scale nowadays, nice kits heres hoping I can do them justice.

The biographic article about RRST is excellent. I enjoyed reading it very much. The paragraph No. 257 “Burma” Squqdron has two minor errors. The reference to 10 June 10 might better be 10 June 40. Then, September 7 . . . Mitchell and Beresford – were lost?

I am looking forward to your release of the Hurricane Mk.I.

Thank you for pointing out the typos. They have now been corrected.

Are you planning a fabric wing Mk.I version as well?

We don’t know yet. Hopefully?

A very good article in general. A couple of points I don’t agree with, but as I wasn’t on 257 Squadron at the time, I will not state categorically that theories are “wrong”.

His name though was Roland Robert Stanford Tuck, not Robert Ronald. Request an amendment, please.

Thank you for name correction!