The history of the 57th Shimbu-tai is inextricably linked to one of the bloodiest and most brutal engagements of the Pacific War, namely, the Battle of Okinawa. For the Allies, the island was the final step – a sui generis gateway through which they would launch an attack on the Japanese home islands. Its extensive infrastructure, the most prominent elements of which were several conveniently located airfields, was to be used to provide critical aerial (and logistical) support for the anticipated invasion. The Japanese in turn viewed the campaign as the last chance to defeat the enemy forces or at the very least seriously cripple them, and thus gain time to properly prepare the defence of the motherland. As regards air operations, the Battle of Okinawa was characterized by the mass use of suicide units. This was not a new method of conducting warfare, but the operations were astonishing because of their scale and the extraordinary determination displayed by the Japanese pilots.

The Beginnings

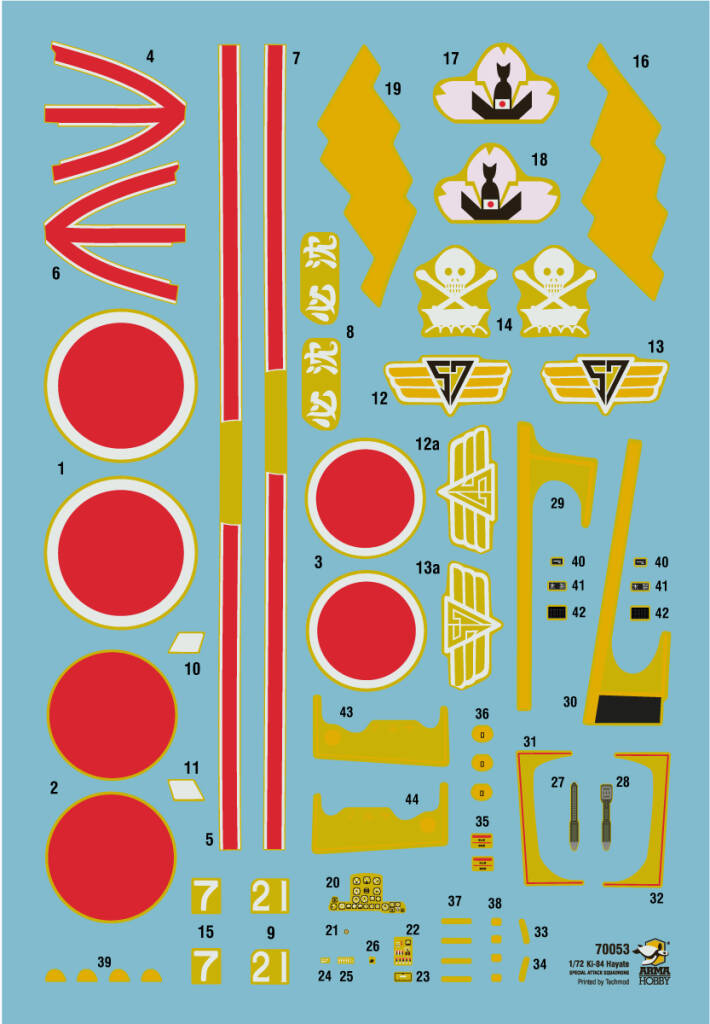

Although the present article is not specifically concerned with a presentation of the operations of suicide units, it is worth briefly recalling their genesis. The first mission, flown by a specially created squadron of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Force (IJNAF), took place already during the fighting for the Philippines – on 25 October 1944, to be precise. The unit in question, known under the name Shikishima and commanded by Captain Yukio Seki, was made up of fighter pilots from 201st Kokutai. Captain Seka’s bomb-laden Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” struck the stern of the escort carrier USS St. Lo (CVE-63), causing numerous fires and secondary explosions which ultimately resulted in the destruction of the ship.

USS St. Lo escort aircraft carrier hit by “kamikaze”

Captain’s subordinates caused damage to several other escort carriers, including USS Sangamon, USS Suwannee, USS Santee, USS White Plains and USS Kalinin Bay. In the eyes of the Naval Staff, the operation was an overwhelming success, especially as in their reports the pilots who flew cover mentioned the complete annihilation of 3–5 enemy carriers. A strong proponent of the suicide attack concept, Vice Admiral Ohnishi, expressed himself as follows: There are thousands of us pilots. But the enemy does not have thousands of ships. And so we shall destroy them all, just like the kamikaze – the “divine wind” – had shattered the invasion fleet of Kublai Chan centuries before. This is how the Naval Special Attack Units, known to us as the kamikaze, were born.

The Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF), however, was rather sceptical about the idea of suicide attacks. But the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff (Gunreibu) had made its decision and issued the relevant orders; there was no way for the Army to avoid involvement as a branch of service. To compound matters, however, the ranks of its own kamikaze squadrons – known as shinfu – were initially supplied mainly by volunteer pilots who possessed considerable combat experience, which was considered an extreme wastage of qualified manpower. During the fighting for the Philippines, the IJAAF deployed twelve suicide units. At the time, they were named hakkō-tai and carried ordinal numbers from 1 to 12. At the beginning of 1945, the programme of recruiting pilots for shinfu units was at once significantly expanded and considerably modified.

57. Shimbu-tai

Squadrons created according to the new principles were named shimbu-tai, while some sources refer to them as shinbu-tai. Both forms are considered correct, as the problem lies in rendering the phonetic sound of the term into English. In any event, orders issued at the turn of April 1945 established the next Army suicide units, namely, 57th, 58th, 59th and 60th Shimbu-tai.

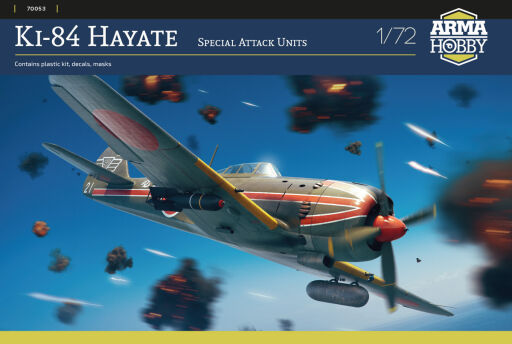

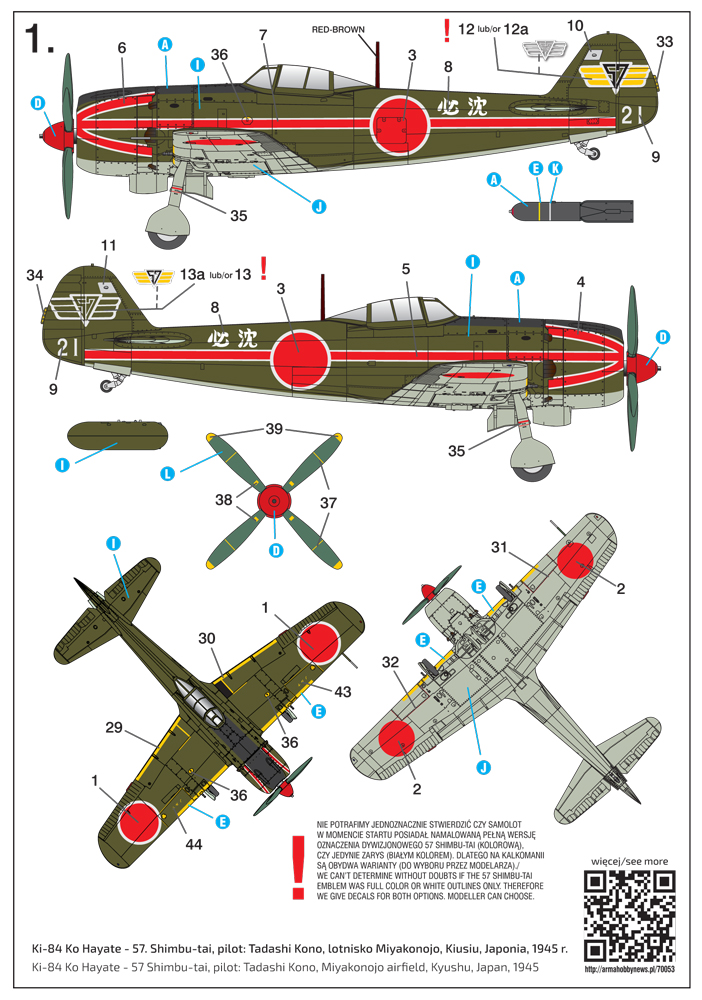

Ki-84 Ko, 57th Shimbu-tai, Miyokonojo airbase, Kyushu, Japan, Okinawa battle period, May 1945

All of the above-mentioned squadrons were staffed by young pilots, students – corporals, sergeants and second lieutenants – of the famous aviation school in Akeno near Tokyo. What do their military ranks tell us? Well, first of all, that after completing a full training cycle, airmen were assigned to combat units in the rank of second lieutenant, while aviators in the rank of corporal or sergeant had gone through an extensive piloting course, but without so-called combat training, which covered the intricacies of aerial combat, such as flying and engaging the enemy in larger formations. These skills, however, were considered as not necessarily needed for suicide missions.

Shimbu-tai units normally had between a few and a dozen or so aircraft, and more or less ten if they were equipped with fighters. Viewed from this angle, a shimbu-tai was therefore equivalent to a Special Strike Squadron. The young pilots from Akeno were transferred to Shimodate air base (also near Tokyo), where their units were actually established and from where they soon departed for Miyakonojō airfield on the southern coast of Kyushu. 59th Shimbu-tai was the first to move south, while the 57th and 58th became operational in mid-May. As a matter of fact, some of the extant photographs of the aircraft and pilots of both units were taken at Shimodate on 17 May 1945. The 60th was to join its sister units a few days later.

The Mission

On the morning of 25 May 1945, 57th Shimbu-tai joined a larger grouping that had been tasked with attacking the American ships deployed north-west of Okinawa. In addition to the ten Ki-84 Kos of the 57th and the same number of fighters from the 58th, it contained three other suicide aircraft of the type. One of them was flown by a volunteer fighter pilot from 1st Chutai, 51st Sentai. This aeroplane (with the white tactical number 925 on its tail) is clearly visible in the famous photograph of 57th Shimbu-tai that was taken in Miyakonojō just before the formation took off. The second Hayate was from 59th Shimbu-tai (due to technical reasons, its pilot had not flown with his unit a few days earlier), while the third was from 60th Shimbu-tai (it had been the first to arrive in Kyushu). Fighter cover for the twenty-three-aeroplane strong kamikaze group was provided by eleven fighters from 103rd Sentai (also flying Ki-84 Kos) under the command of Captain Ogawa. Due to the Ki-84’s less than impressive range, they were equipped with two additional fuel tanks, while the strike aircraft were fitted with a single bomb and one underslung fuel tank.

The Results

Unfortunately, the exact course of events is not known. Of the entire group of thirty-four Hayates, only the aircraft piloted by Captain Ogawa, damaged, returned to Miyakonojō. In his account he stated that at around 11:00–11:15 local time, while flying north of Okinawa, the Japanese expedition became engaged in a violent dogfight with a large formation of P-47 fighters. Ogawa reported shooting down two of the Thunderbolts, but was unable to shed any light on the fate of his comrades. American documents indicate that the unit responsible for the massacre of the Hayates may have been 318th Fighter Group. Flying P-47s, it conducted patrols for most of the day and repeatedly clashed with enemy groupings of various sizes. However, it reported the fiercest engagement at a time and place very similar to those mentioned by Ogawa, namely, in the morning hours near the island of Ie Shima off the northern coast of Okinawa. The Japanese force was described as comprising about thirty aeroplanes, probably A6M “Zeroes”. At the end of the day, the pilots of 318th FG claimed thirty-four aerial victories in several separate clashes, but without any losses of their own (and thus raising doubts as to the victories reported by Captain Ogawa).

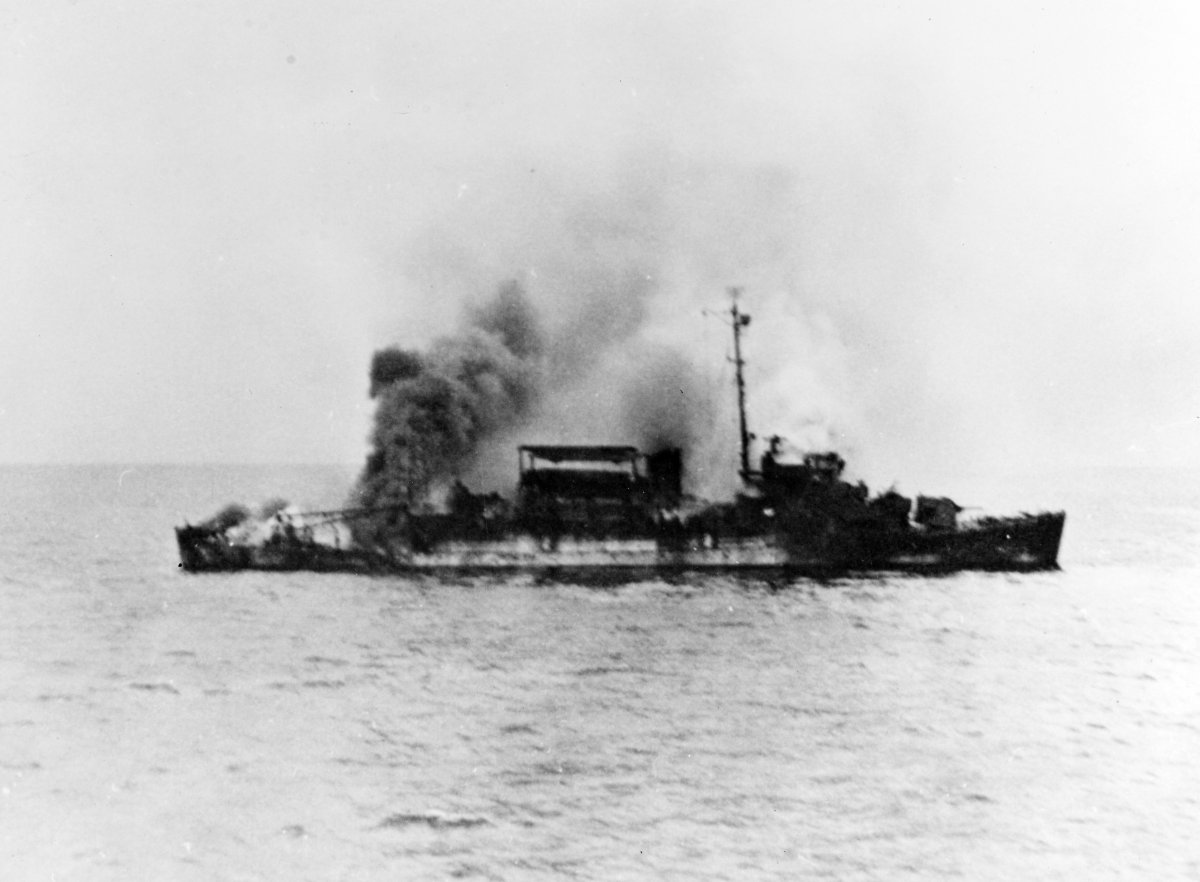

Despite the intensity and scale of the kamikaze operations organised by the Navy and Army, on 25 May 1945 the Americans lost only the fast transport ship APD-47 (allegedly to a Ki-51 Sonia), while the destroyer USS Stormes (DD-780) was severely damaged, purportedly by a Yokosuka D4Y Judy dive bomber. In other words, we may presume that the pilots of 57th and 58th Shimbu-tai failed utterly in their mission … except that reports on the sinking of APD-47 say one thing, while those concerning the loss of the USS Bates – something completely different. What do these two ships have in common? Namely, that towards the end of 1944 the destroyer USS Bates (DE-68) was rebuilt into the fast transport ship APD-47, and it was under this designation that it took part in the Battle of Okinawa. It was therefore one and the same (although physically different) vessel, however the circumstances of the sinking of DE-68 and APD-47 differ in US Navy documents.

USS Bates (then already APD-47) was attacked not by a single Ki-51, but by three fighter-bombers (!). The first dropped a bomb on the ship, and then proceeded to make a suicide attack. The second crashed into the vessel already in the course of the preceding attack, while the third dropped a bomb and crashed into the ocean when trying to recover from its dive. Most importantly (and this I would like to stress), the attack took place 2 nautical miles south of the island of Ie Shima at around 11:15 local time – that is, at the same exact location and time when the fighters of 103rd Sentai engaged the Thunderbolts of 318th FG. USS Bates aka APD-47 lost twenty-one crewmen, while the rest abandoned the vessel at 11:45. The tugboat USS Cree tried to tow the burning ship to the vicinity of Ie Shima, but the attempted rescue was unsuccessful and the vessel sank at around 19:30. We cannot be certain whether the sinking was orchestrated by the pilots from “our” expedition, however circumstances suggest that this was highly probable.

The Aicraft and its Pilot

The pilot of the Ki-84 Ko with the distinctive arrow motif and white tactical number “21” was Megumu Takano. His rank has been variously given, with some sources describing him as a corporal, others as a sergeant, and others still as a ensign. Interestingly, each of these presentations is correct. Namely, it was customary for the commanders of shinfu units – and sometimes also section commanders – to be promoted by one rank on the eve of their last mission (wartime promotion). Thus, Takano left Akeno in the rank of corporal, and was promoted to sergeant at Miyakonojō. But this was not all, for the commander of 57th Shimbu-tai assigned him the role of “unit flag-bearer”, that is, ensign or standard-bearer. In other words, Takano was a corporal promoted to the wartime rank of sergeant, and also the flag-bearer (a ensign) of the 57th. This also explains, albeit indirectly, why his aircraft bore such elaborate markings.

Above the arrow are white ideograms proclaiming “Confident of Victory”. The motto of the 57th may be roughly translated as “Certain of Death – Certain of Victory”. Initially, only a photograph of one side of the fuselage was known, and it was assumed that some part of the “Certain of Death” motto was located on the other side.

However, when more pictures were found, it turned out that the inscriptions on both sides were identical. Thus, the aircraft of the unit’s “flag-bearer” carried only the optimistic portion of the maxim. So what happened to the pessimistic part? Interestingly, it was accepted by Lieutenant Tetsujiro Karasawa, and his Hayate was duly adorned with ideograms standing for “Certain of Death” or, to apply a more literary turn of phrase, “Death is Inevitable”. Behind the markings we can see an area covered over with fresh paint, however there is no certainty that the second part of the motto was originally located there. Who knows, perhaps this was a method used to remove redundant designations?

Nineteen-year-old sergeant Megumu Takano, born in Chiba Prefecture and a graduate of the 14th class of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force, was posthumously promoted to the rank of second lieutenant. Some of the letters which he wrote at Miyakonojō and sent to his parents have survived, and are part of the collections of the Chiran Peace Museum, which is dedicated to the memory of the Special Attack Units pilots.

Check also:

Buy Ki-84 Hayate Special Attack Units model kit in the Armahobby.com store online!

A lover of strong coffee and dark chocolate, incurable optimist, romantic and dreamer, economist by education, historian and modeller by passion. From time immemorial he has been fascinated with aviation in every variety and form. For many years, he has been paying special attention to all aspects of the activities of the Army and Navy Aviation of the Land of the Rising Sun.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski