47th Sentai (Air Group) went down in history as one of the best and most effective fighter units of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF) in the Second World War. It acquired its fame mainly through its success in fighting off B-29 bombers during the Allied strategic offensive aimed against the heart of Japan. In fact, the unit came second on the list of the so-called “B-29 Hunters”, behind the famous 244th Sentai of Major Kobayashi and in front of 302nd Kokutai (Naval Aviation Group), led by the charismatic Commander Kozono. Interestingly, of these, only 244th Sentai was created in a standard manner, in accordance with the rules laid down for the formation of basic Japanese aerial tactical units which had been developed towards the end of the first half of the 1930s. 302nd Kokutai was a completely unusual unit, while the history behind the establishment of 47th Sentai was equally atypical.

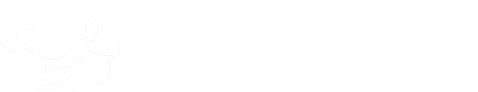

Ki-84 Ko, 3 Chutai 47 Sentai commander’s Cpt. Hatano airplane Japanese Home Defence Forces (Hondo Boei Butai), Narimasu, Japan, February 1945. Artwork by Zbyszek Malicki.

The Beginnings – “Kingfisher Flight”

In August 1940, the Japanese Army launched the prototype of a completely new fighter – the Ki-44 Shoki (Tojo). The aircraft marked a radical departure from the accepted canon. Unlike its predecessors, the Ki-27 and Ki-43, it was not intended to be a light, extremely manoeuvrable dogfighter. On the contrary, according to the contemporary Japanese classification it was a very fast, strongly armed, heavy single-seater interceptor. These features, although attractive in their own right, were in serious contradiction to the principles of usage of the IJAAF, and in particular to the pilot training doctrine of the time. Simply put, the issue had to be dealt with – somehow. This task was entrusted to a group of highly experienced pilots: veterans of the Sino-Japanese War and the fighting over Khalkhin Gol, test pilots, as well as outstanding air combat instructors. On 15 September 1941, the “Kingfisher Flight” – Kawasemi Butai (Kawasemi-tai) – was established at Fuss airbase. It comprised no less than eight (out of ten) Shoki prototypes, and later a few early-series Ki-44-Is. Experienced pilots needed about two months of training on the new fighters in order to gain complete familiarity. There remained, however, the question of developing appropriate combat tactics, totally different from that employed hitherto. In November, the Kingfishers were moved to Tachikawa airbase and officially renamed as 47th Dokuritsu Hiko Chutai (DHC; 47th Independent Fighter Squadron). The unit was transferred to Saigon in Indochina (present-day Vietnam) and entered combat in Malaya on 9 December 1941. It was commanded by Major Toshio Sakagawa from the IJAAF, who went on to become an ace with 15 officially recognized victories (according to some sources, he racked up a tally of nearly 50 kills). Many other pilots also gained ace status, among them Captain Yasuhiko Kuroe, who came out victorious from 51 aerial duels and years later, in the 1960s, was appointed commander of the 3rd Tactical Fighter Squadron of the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force (JSDAF), which flew the F-86 Sabre. During the Malay campaign the pilots of 47th DHC did not achieve any stunning successes (mainly due to Shoki’s teething problems), however this had not been their main goal. The operational methodology which they developed for the new fighter would soon be appreciated by their colleagues from 85th and 87th Sentais, who were currently being rearmed with the Ki-44-I. When the first phase of the blitzkrieg in the Asia-Pacific theatre drew to a close, 47th DHC was sent back to Japan.

Nakajima Ki-44-II Otsu, Clark Field 1945, Wikipedia.

The Spring of 1942 – Change, Change, and Yet Again Change

The return of 47th Dokuritsu Hiko Chutai to the home country coincided with a series of events of fundamental importance. These events influenced not only the further fate of the unit, but also (or perhaps first and foremost) the entire structure of the IJAAF. The turning point occurred on 18 April 1942, when a group of sixteen B-25 Mitchell bombers commanded by Colonel Doolittle attacked Tokyo, Nagoya, Kobe and Osaka. Although official communiques mentioned “merely a pin stuck in the heart of the country”, all hell broke loose in military circles. The raid had numerous repercussions, the best known of which was the development of the plan for the Battle for Midway, which anticipated, among others, trapping and annihilating the American aircraft carrier force. Things turned out differently, however Midway was a problem for the Navy. The Army itself was stunned by the fact that several hundred IJAAF planes stationed on the Japanese islands had failed to achieve anything at all on that dark day.

The reorganization of aerial forces led to the introduction of the “Kokugun” – the Air Army. The first three Kokuguns were formed in May 1942, less than a month after the Doolittle Raid. 1st Air Army (with its headquarters in Tokyo) was responsible for the home islands area and for the Kuril Islands right up to Sakhalin; 2nd Air Army covered Manchuria, Korea and North East China; while 3rd Air Army was tasked with protecting Malaya, Burma, Indochina and the Dutch East Indies. Later, three more Kokuguns were established: one covered the area from New Guinea to the Philippines, the second was responsible for central China, and the third was intended to strengthen the defences of Japan.

Upon its return to the homeland, 47th Dokuritsu Hiko Chutai was immediately incorporated into 1st Kokugun and expanded to a full Sentai (comprising a headquarters section and three squadrons – Chutais). Given the planned nature of its operations (as well as the experience which it had gathered to date), it was one of the few Sentais to be equipped exclusively with Ki-44 interceptors. The personnel composition of 47th DHC could not be maintained, however much effort was put into turning it into an elite squadron. In June 1942, the structure of 1st Air Army was further developed by the creation of specialistic Hondo Boei Butai (Japanese Homeland Air Defence) units. 47th DHC was made subordinate to the Homeland Air Defence and allocated to the Tokyo and Kanto Plain area of operations. Thus, 47th Sentai became a sui generis guard protecting the very heart of the Empire, with which its early history became closely intertwined.

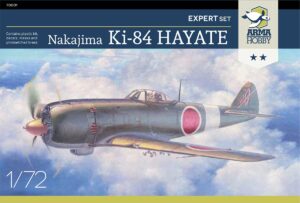

While the original line-up of 47th DHC was known as the “Kingfisher Squadron”, Headquarters assigned this experimental-combat formation the code-name Shinsengumi. This term referred to a group of samurais who in the Edo period were distinguished by their absolute (or even fanatical) loyalty to the “Code and Country”, forming the defensive core for feudal Japanese tradition and culture. In the mid-19th century, in the face of growing American (and, in general, Western) influence, the motto of the Shinsengumi troops was changed to “sonnō-jōi”, which meant more or less “restore the due and proper standing of the Emperor, expel barbarian foreigners”. Regardless of the word games played by the Japanese staff officers, the pilots of 47th Sentai just carried on with their jobs. Their tool was the Nakajima Ki-44 fighter, decorated with white stripes (“bandages”) under the Hinomaru – a characteristic element signifying affiliation with the Hondo Boei Butai. Of course, this decorative nuance was not included due to aesthetic considerations. The bandages were intended to enable the quick identification of aircraft, in particular by their own anti-aircraft artillery.

In the autumn of 1944, the unit was stationed at Narimasu airfield (on the north-eastern outskirts of the capital) and formed part of 10th Hikoshidan (10th Air Division) commanded by Major General Kihachiro Yoshida. The role of 10th Division was to defend the eastern frontiers of Japan, and in particular the area of Tokyo, Nagoya and Yokohama. In addition to 47th DHC, the Division comprised 17th and 244th Sentais (flying the Ki-61 Hien), 23rd Sentai (the Ki-44 Shoki), and 53rd Sentai (the Ki-45 Toryu). 28th Sentai (reconnaissance), which was in the course of having its Ki-46 Dinah reconnaissance aeroplanes replaced with the aircraft’s fighter version, the Ki-46-III Otsu, was also preparing for the fight. It was these units that were to handle the lion’s share of clashes with the B-29 bombers flying from airfields in the Mariana Islands (Guam, Saipan and Tinian) into the heart of the Empire (in November, December and January).

However, already towards the end of December 1944 orders came through to gradually re-equip the unit with a new type of fighter – the Hayate (English: the Gale). This decision was difficult to understand, for although the Ki-84 had generally excellent handling characteristics, it was more or less a failure at the operational altitudes of the “B-san”. As a fighter, it was optimized for combat at altitudes of 3,000–4,000 meters, and was practically useless above 7,000 meters (whereas B-29 missions of the period were usually conducted at approximately 9,000 meters). Headquarters, however, were aware that the failure of the Philippines defensive campaign, which was drawing to a close, would bring more immediate threats to the home islands than the American bombing offensive. Either way, equipment replacement was to be completed in early February 1945, and the deadline was kept. Towards the end of the first decade of month, 1st Chutai (known as “Asahi-tai”), 2nd Chutai (Fuji-tai) and 3rd Chutai (Sakura-tai) were ready to fight on their new steeds.

16–17 February 1945 – Days of Trial

The fears of the IJAAF Command Army Aviation Command materialized in the worst way possible. The American sea landing on Iwo Jima commenced on 19 February. Before this, however, it was necessary to neutralize the aerial (and if possible naval) forces deployed on the eastern seaboard of Japan. Thus, the airfields and naval bases of the region became the main target of the operation. On 10 February, the ships of Task Force 58, commanded by Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher, left their anchorages on Ulithi Atoll. The core of the group consisted of sixteen aircraft carriers with one thousand aircraft. TF 58 passed near the Mariana Islands, and in the next few days sailed around Iwo Jima in a wide arc from the east. On the cloudy morning of 16 February, the American vessels were 60 miles off the coast of Honshu and approximately 120 miles from Tokyo.

„Big E”

Since I have already mentioned the symbolism so characteristic of the cultures of the Far East, it should be noted that the Americans, too, had their “totem” in the campaign: the USS Enterprise (CV-6), affectionately called “Big E”. The carrier had taken part in the Doolittle Raid, protecting the USS Hornet carrying the B-25 bombers. The Hornet was lost in October 1942 in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, but the Enterprise survived and after almost three years returned to Japanese waters in the first Allied operation since the attack on Tokyo.

Photo: USS Enterprise in 1945 , Wikipedia.

The first phase of the raid progressed calmly, without any particular activity on the part of the defenders. However, after nearing the Imperial capital the squadrons from USS Lexington (CV-16) and USS Hancock (CV-19) encountered strong resistance from IJAAF fighters, estimated at more than 100 strong. A fierce battle ensued, during which the Americans incurred serious losses. Contrary to Mitscher’s clear orders to keep formation no matter what, many young pilots engaged in dogfighting with the Japanese – and paid for their nonchalance with their lives. The attack undertaken by other units on Yokosuka naval base had a similar outcome (albeit on a slightly smaller scale), although their opponents there were aviators from the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service. On 17 February, the assault was repeated, however due to the constantly worsening weather it focused on secondary targets (factories and aircraft production plants). In the course of the two-day battle, American pilots reported destroying nearly 500 (!) enemy aircraft (both in the air and on the ground) and dozens of ships and smaller surface vessels, and also causing great damage to the infrastructure of bases. These reports, however, were not considered credible by intelligence officers, and photos taken by a Boeing F-13 (the reconnaissance version of the B-29) soon confirmed that their suspicions had been correct. Indeed, the effectiveness of the raid had been at best symbolic. No air or naval base had been significantly damaged. The airfields were nearly empty, with no trace of the “hundreds of wrecks” mentioned by the strike groups. The only real success consisted in the sinking of the huge transport vessel Yamashiro Maru, with a displacement of 10,600 GRT, and inflicting serious damage to several smaller vessels. Some damage was also reported by three aviation plants near Tokyo. The number of kills was revised and brought down to 50–60. These results were achieved at the cost of 60 aircraft lost in combat and approximately 30 forced to ditch on the way back or destroyed while crash-landing. Over a hundred others suffered severe damage. However, the use of the TBM Avenger RCM (Radar Counter Measures), which was tasked with detecting and “dazzling” coastal radar systems, was considered a tangible success. TF 58 withdrew to the vicinity of Iwo Jima (to support the landing forces), and the operation – considered a fiasco – became the focus of an in-depth analysis aimed at drawing conclusions as to the methodology that should be employed in upcoming clashes.

And how did the situation look from the perspective of the IJAAF and, in particular, 47th Sentai? The aviators of 10th Hikoshidan were the “more than a hundred aircraft” defending the Tokyo area, although according to their accounts, they attacked the seven successive waves of the air raid in smaller groups many times during the day (16 February). Once the clashes drew to a close, they reported 62 confirmed kills and 27 enemy aircraft damaged. The experienced pilots of 47th DHC were overjoyed by their foe’s lack of discipline and exploited it to the full, accounting for 16 Grumman F6F-5 Hellcats and two SB2C Helldiver dive bombers. The majority of these victories were scored by 26 Hayates over Ota airbase, with Captain Hatano’s Sakura-tai being most active. But their success cost the lives of Warrant Officer Nakajima and Sergeant Nakanishi. On 17 February, neither 47th DHC nor 244th Sentai entered the fray. Command concluded that the effects of the American attacks were negligible and that highly experienced pilots should not be sacrificed without good reason (on the first day, 10th Hikoshidan lost 37 pilots). The second day of fighting in the Tokyo area was handled mainly by 22nd and 52nd Sentai, which for the loss of 14 pilots claimed 36 confirmed kills and 18 enemy aircraft damaged.

Pilots of 3rd Chutai from 47th Sentai being debriefed between missions on 16 February 1945. Captain Hatano is standing in the foreground, with Hayate “yellow 45”, adorned with two stripes identifying the Sakura-tai commander, in the background. The remaining pilots (from left to right): Lieutenant Itsuro (Hatano’s wingman), Lieutenant Kobozoe, Lieutenant Ichiraku, Warrant Officer Nakajima (perished), Lieutenant Ishihara, Sergeant Nakanishi (perished), Sergeant Aruga, Sergeant Maruyama and Sergeant Yamazaki.

Okinawa

Withdrawn from the front line, 47th Sentai received a categorical order prohibiting it from engaging in any combat with American aerial forces: both carrier-borne fighters and B-29 bomber groups (which by then were flying low altitude night carpet bombing missions). It was to remain in reserve for the invasion, which was considered imminent.

On 1 April 1945 (L-Day), troops of the American XXIV Corps and III Amphibious Corps started landing on the beaches of Okinawa. This marked the beginning of a fierce, two-and-a-half-month-long battle for the island. Suicide planes, first used in the fighting for the Philippines, were now used on a mass scale. During the first phase of the campaign, the IJAAF threw three Assault Groups into the fight. They comprised four fighter regiments and a dozen or so suicide units (Shimbu-tai). The task of the experienced 59th Sentai (flying the Ki-61 Hien), which had hitherto fought as part of the Hondo Boei Butai, consisted in protecting the airbases which the Americans dubbed “Kamikaze nests”. The role of the recently created 101st, 102nd and 103rd Sentais (equipped with the Ki-84 Hayate) was to provide direct cover for suicide missions and (from mid-April) conduct fighter-bomber attacks on those of Okinawa’s airfields that had been captured by the enemy. The units suffered immense losses. Over approximately 6 weeks, 101st, 102nd and 103rd Sentais lost nearly 80 pilots. Initially equipped with more than 120 Hayate fighters, the three units were reduced to no more than 15–18 aircraft. In this situation Command was forced to scrape the barrel for reserves.

Photo: USS Enterprise hit by kamikadze – near Okinawa, May 1945, Wikipedia.

Towards the end of May, 47th Sentai set off for Miyakonojo on the southern tip of Kyushu Island. Its task was to provide fighter cover for the 18th, 19th, 25th, 45th and 47th Shimbu-tai suicide units. The force was supplemented with 244th Sentai (freshly equipped with the Army’s most modern fighter, the Ki-100 Goshikisen), which was made responsible for protecting the direct vicinity of the airbase. But even the rich experience and immense dedication of the pilots of both units could not hope to challenge the absolute domination of Allied military aviation. The Sentais achieved some success, however incurring heavy losses, and in the second half of June, with the fighting started to die down, they were withdrawn north for refitting and re-equipment.

Epilogue

Ozuki airfield, a base located near the city of Shimonoseki on the southwest coast of Honshu, halfway between Hiroshima and Nagasaki, became the 47th’s new home. Refitting proceeded very slowly. The numbers of newly arriving Hayates dwindled steadily, while the level of workmanship was such that ground crews had to perform miracles in order to prepare the aircraft for combat. Worse still, the young pilots posted to the unit had received only basic training, and possessed no more than elementary piloting skills. But it was the enemy – not technical and organizational woes – that brought about the 47th DHC’s “blackest day”. On 28 July, a large group of P-51D Mustangs appeared over Ozuki on a classic fighter sweep. The 47th DHC’s fighters, caught during take-off and thus deprived of any real possibility of defence, were massacred by the attackers. Eight Ki-84s were destroyed, and six pilots perished. Among the fallen were all the Chutai commanders: Captain Ohmori, Captain Matsuzaki and Captain Hatano. On 1 August, by which date the unit comprised nearly only young and unexperienced pilots, an attempt was made to intercept a group of B-24 Liberator bombers. However, they first had to pit themselves against the Mustangs of 460th Fighter Squadron, 348th Fighter Group, which shot down four Hayates without any own losses. It is worth noting that 348th Fighter Group had entered the war in New Guinea, and was commanded at the time by the (late) ace and recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor, Colonel Neel Kearby. Until the end of the Philippines campaign, it had operated the P-47 Thunderbolt.

47th Sentai flew its last mission at noon on 14 August 1945. Eight Ki-84s commanded by Lieutenant Oishi managed to jump a section of P-51Ds that were reconnoitring over the Bungo Strait. The Japanese avenged their fallen commanders, reporting five aerial victories for the loss of one pilot (Warrant Officer Nakamura). Exactly 24 hours later, the Emperor of Japan announced the termination of hostilities. The communique was listened to by some thirty pilots standing in readiness near the unit’s last 23 Hayates.

Pilots from the aerial ramming section (Shinten Seiku-tai) of 47th Sentai and their superiors. First row (from left to right): Takayoshi Nagasaki, Isamu Sakamoto, Noboru Okuda, Suguru Suzuki, Yoshio Mita. Second row (from left to right): Captain Hatano (3rd Chutai), Captain Shimizu (1st Chutai), Captain Yasuro Masaki (2nd Chutai). Narimasu airfield, 7 November 1944.

English translation by Maciek Zakrzewski

See also:

A lover of strong coffee and dark chocolate, incurable optimist, romantic and dreamer, economist by education, historian and modeller by passion. From time immemorial he has been fascinated with aviation in every variety and form. For many years, he has been paying special attention to all aspects of the activities of the Army and Navy Aviation of the Land of the Rising Sun.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski