On 22 February 1941, William John “Jack” Storey left Sydney port on a round-the-world journey that would last more than three years. It proved to be a long and dangerous odyssey, but one with a happy ending for our protagonist. “Jack” went on to live to a ripe old age and readily recounted his wartime adventures, which we will try to summarise in the present article.

When he was embarking on his voyage, he had just completed basic flying training on Tiger Moths at No. 5 Elementary Flying Training School RAAF in Narromine after first volunteering for the Air Force in the spring of 1940. The destination of the first stage of his journey was Canada, where he passed training on Harvards at No. 2 Service Training Flying School in Uplands with excellent marks. A photograph taken on 23 May 1941 shows twenty-four fresh graduates of Course No. 23, all of them from the Royal Australian Air Force. Of this group, fourteen perished during the war. Storey is in the first row, second from right. In the second photograph we can see Clarence Decatur Howe, the Canadian Minister of Munitions and Supplying, pinning pilot’s wings onto Storey’s uniform. (Flying Badge).

Jack Storey at No. 2 Service Training Flying School in Uplands (Canada), see description in text above. Both photos from the blog: http://rcafuplands.blogspot.com/

A few days after finishing the course, Storey was promoted to Pilot Officer and posted to England, crossing the ocean in a convoy under constant U-boat attack. Following his arrival, he busied himself with completing the final level of flying training.

Since he had received excellent grades at the course in Uplands, he was allowed to choose the aircraft on which he would undergo operational training. At No. 59 Operational Training Unit, which was stationed at RAF Crosby-on-Eden, he immediately selected the Hurricane.

A Devotee of the Hurricane

Storey’s entire military career was associated with this aircraft, which in his opinion had proved decisive for the outcome of the Battle of Britain. As a pilot, he had a lasting fondness and admiration for the type, considering it superior to the Spitfire itself. In Storey’s view, Supermarine’s fighter lacked durability and reacted inadequately to elevator inputs. He further stated that the Spitfire’s thin wings had a tendency to deform, while their angle of attack at high gravity load was insufficiently flexible, and these factors impaired the accuracy of its wing-mounted machine guns. He was right. The Hurricane on the other hand was a very sturdy aircraft, so much so that it has even been said that not one of the 15,000 built crashed due to structural failure. It was tolerant of even the most brutal manoeuvres. In fact, it was considerably more resilient than its operators, who would react variously to gravity loads. It was observed that pilots who were smaller in stature were least susceptible to these forces, starting to experience greyout only at higher gravity loads and still being able to react correctly in situations which caused their taller colleagues to black out. Storey himself, measuring no more than 162 cm (5’ 4’’) and weighing approximately 50 kg, was predisposed by nature to tolerate the physical loads experienced during aerial combat and could therefore fully harness the manoeuvrability of his Hurricane while knowing that his fighter would not let him down. The robust aircraft and its well-trained pilot combined to form a duo that proved to be extremely dangerous to the enemy.

The Beginnings of No. 135 Squadron

Storey’s first posting was to No. 135 Squadron, which had been formed in August 1941 at RAF Honiley, a few miles south-west of Coventry. The unit was commanded by S/L Frank Carey, an enormously experienced pilot who had scored nineteen confirmed kills in fighting over France and England in 1940. Carey, although deserving of a more in-depth presentation, can only be mentioned briefly in our article, however mentioned he must be, for he became our protagonist’s mentor and thus forms an inseparable element of his life story.

Storey’s unit did not take part in the aerial offensive over occupied France, and it was scrambled to intercept unidentified aircraft (which in the majority of instances turned out to be friendlies) on only a few occasions. Years later, Storey would recall – not without a hint of irony – that one of his operational flights while stationed in England, during which he attempted (unsuccessfully) to intercept a reconnaissance Ju 88, turned out to be enough for him to be awarded the Air Crew Europe Star post-war.

Plans were soon made to send the squadron to the USSR, where it was to fight in the southern sector of the Eastern Front in support of British land forces which were to be tasked with securing the Caucasian oil fields against the rapidly advancing Germans. At the beginning of November 1941, the unit finally received orders to commence an overseas deployment, and on 10 November its ground crews set sail from Liverpool to Iraq. The squadron’s 20 pilots, however, were given an unusual and difficult task. Once they reached Gibraltar, they were to embark on the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal and, after making Alexandria in Egypt, some 800 km distant, take off from the ship with their fighters fitted with additional fuel tanks. A considerable part of the planned flight would have taken them through an area controlled by the German and Italian Air Forces. But the sinking of HMS Ark Royal on 14 November 1941 forced the plan to be abandoned, thus allowing the pilots, who had never before flown such distances over sea, to avoid the risk of being shot down or getting lost over the Mediterranean. The squadron disembarked in Takoradi and, using various means of transport, travelled the continent to Cairo. It was only there that they learned that their destination had been altered following the Japanese attack on Malaya, and that they were being sent to bolster the aerial defences of Burma, which at the time were made up of 16 Brewster Buffaloes from No. 67 Squadron (14 other Buffaloes comprised a reserve) and 21 Curtiss P-40Bs from the American Volunteer Group’s 3rd Pursuit Squadron (“Hell’s Angels”).

Storey now had another ocean to cross.

Hurricane Z4726, with temporary markings painted for delivery from Port Sudan. Aeroplane piloted by S/L Cedric “Bunny” Stone damaged in the first combat on January 23, 1942 and nevewr returned service. Photo from the book by Norman Franks “RAF Fighter Pilots Over Burma”.

En Route to Burma

They departed Cairo on a BOAC-operated Sunderland and, after weeks of travel, landed on a river near Rangoon on 19 January 1941, being greeted by the sight of a Japanese aerial bombardment of the city. But only Storey and Carey reached their destination that day; the rest had had to make room for army officers on their way to Singapore. The ground crews of No. 135 Squadron were already at Zayatkwin airfield, where they had been waiting for both pilots and aircraft since 16 January. No. 267 Fighter Wing, which was tasked with the defence of Burma, had its main base at Mingaladon (a pre-war civilian airfield north of Rangoon) and was officially made up of three squadrons: No. 17, No. 135 and No. 136. It received its first three Hurricanes only on 23 January; the fighters were flown in by aviators from No. 136 Squadron, which, interestingly, was deprived of its mechanics, who were stuck in Karachi. The aircraft were taken over by No. 17 Squadron and immediately sent into battle, however the haste was such that no one thought of removing their underwing fuel tanks, and – while we cannot have certainty – this could very well have been the reason why one was damaged and rendered inoperable by Japanese fighters in the very first engagement. That evening, the tanks were quickly removed from the two other Hurricanes, but there was no escaping the fact that on the morning of 24 January No. 267 Fighter Wing had just two Hurricanes ready for action at Mingaladon. As it turned out, No. 136 Squadron’s stay in Rangoon lasted only a short time – it was quickly sent to India, while its pilots were distributed between the two other units.

The Hurricane Versus the Ki-27

By 15 February, deliveries made to Rangoon by air from Port Sudan, proceeding through Oman and India, had provided the Wing with 30 more new Mk.IIbs.

This immense organizational effort enabled the establishment of an on the whole effective defence against Japanese attacks, with the enemy’s air superiority over Burma being neutralised for most of the time until the fall of Rangoon – a feat that proved impossible to replicate in the Singapore and Java campaigns. The RAF pilots were further aided by the fact that Nos. 77 and 50 Sentai – which were their main opponents in the aerial combat over Burma – were equipped with the Ki-27 “Nate”, which by the early months of 1942 had lost much of its fear factor. Its maximum speed at an altitude of approximately 10,000 feet was very close to that of the Hurricane fitted with a tropical filter. But at 13,000 feet the Hurricane was clearly superior. Further, being deprived of cockpit armour and self-sealing fuel tanks, and armed with only two 7.7 mm machine guns, the Ki-27 found itself at a considerable disadvantage. This was offset to an extent by the experience which Japanese pilots had gained during fighting in China and in the border conflicts with the USSR, as well as by the manoeuvrability of their aeroplanes. While the former could not be immediately counterbalanced, the significance of the latter – the Ki-27’s manoeuvrability – could be minimised provided that Hurricane pilots adhered to specific battle tactics. Storey did not attempt to engage in dogfights with the more agile Japanese fighter, instead following the recommendations of Colonel Chennault, the commander of the American Volunteer Group, who advocated energy fighting in the vertical. Storey gave a detailed description of his method of jinking and taking the initiative in combat. Whenever an enemy aircraft got onto his tail, he would perform a half barrel-roll followed by a vertical spiral dive, making it extremely difficult for the attacker to fire accurately. After diving and accelerating his fighter to 400–420 mph (640–680 km/h), he would draw back on the stick with all his strength, balancing tentatively between a greyout and losing consciousness, and then execute a rapid climb, regaining both height and tactical advantage. If the Japanese pilot followed him in pursuit and proceeded to pull out of the dive, he would be unable to close in further in order to lead his target without blacking out. The Hurricane’s superior acceleration, higher dive speed and legendary sturdiness – mentioned previously – assured Storey that he could escape even the tightest squeeze. These were no mere boasts, for throughout the war his aeroplane was ever only once hit by a bullet fired from a Japanese fighter. He had greater reservations, however, about attacking ground targets, for then survival depended more on luck than on skill.

Two 135 Squadron ground crewmen at Hurricane Z5659/WK-C. Photo from the book by Norman Franks “RAF Fighter Pilots Over Burma”.

The First Clash With the Japanese

First combat flight, first encounter, first “kill”. Everything happened in the space of forty-five minutes after take-off at 15:15 on 29 January. Storey had not sat in the cockpit of a Hurricane for nearly three months. He left base in a pair with Carey in Hurricane BD921, which officially belonged to No. 17 Squadron. While patrolling at a height of over 17,000 feet, they spotted Japanese aircraft heading for their airfield at a much lower altitude. The first attack on the six Ki-27s was ineffectual. Carey only managed to fire off a short burst before the enemy hid in the clouds, while Storey did not even get into a shooting position. He would later recall that at a speed of some 450 mph he had been unable to properly sight his target. After a rapid climb, the two airmen found themselves at approximately 15,000 feet and renewed their assault when the Japanese aircraft left the cloud-bank. This time, however, they did not drop nearly vertically onto their opponents but instead lost height in a wide, rightward spiral at maximum speed, allowing themselves more time to select targets and choose the moment of attack. Storey hit a Ki-27 from close range, smashing the cockpit canopy. The Japanese aeroplane went into a sudden dive and once again disappeared in the clouds. Storey chased after him, however upon exiting the clouds he could not find the enemy. After landing, he reported only damaging one of the Japanese fighters, as he had not witnessed his opponent crash. A subsequent analysis of the encounter, together with oral statements given by airfield personnel, made it possible to determine that the Ki-27 which had been hit by Carey had fallen vertically to the ground, while the second aircraft had flown out of the clouds above the airfield and, proceeding shakily, directed itself towards a group of Blenheims parked at its edge, smashing down in their vicinity. This fighter was claimed by American pilots from the American Volunteer Group, however an inspection of the body determined that the airman had been wounded by 0,303 Browning ammunition fired from a Hurricane.

This was not the only instance when a Japanese pilot, having been wounded or suffering damage to his aeroplane which precluded a return to base, had decided to launch such a desperate assault. A day earlier, a similar suicidal attack had been carried out by 1st Lt Kanekichi Yamamoto, who had targeted a parked Tomahawk. In Burma, Allied aviators encountered opponents who were extremely determined, tenacious, eager to fight and always ready to make best use of the advantages of their aircraft. At the time there were many stories making the rounds (some were even published in the press) that the Japanese pilots had weak eyesight, or that the shape of their skulls caused the gravity loads experienced in aerial combat to cause brain compression and a rapid loss of consciousness. It would be interesting to hear what the pilots of No. 267 Fighter Wing – who came up against their opponents daily – would have had to say about such sensationalist journalism. Storey was tremendously impressed by the gunnery skills of Japanese fighter pilots, whom he viewed as masters at leading a target in a turn. Quite obviously, such an enemy commanded respect, and the considerable losses of experienced British and American pilots suffered during the first few weeks of fighting clearly illustrated that any claims of obvious superiority over the Japanese Air Force and its personnel were very wide of the mark.

Jeden z nowo przybyłych Hurricane. Do pierwszej walki 23 stycznia 1942 r. wystartowano z zamontowanymi dodatkowymi zbiornikami. Photo from the book by Norman Franks “RAF Fighter Pilots Over Burma”.

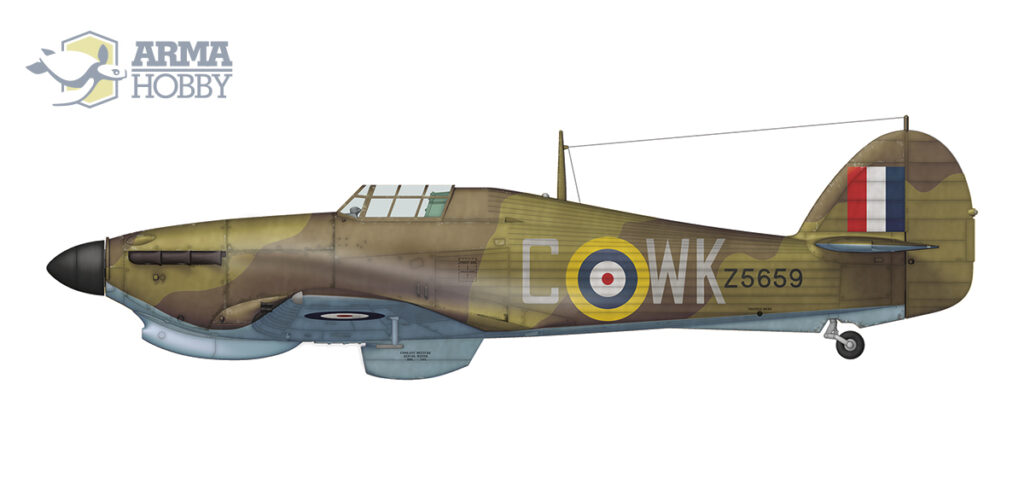

Following the fighting over Mingaladon on 29 January, enemy attacks ceased until 4 February. No. 77 Sentai’s losses in the initial stages of the Burma campaign (from 11 December 1941 to 7 March 1942) were indeed heavy, totalling 28 aeroplanes and as many as 26 airmen. During this time, the aerial defences of Rangoon continued to be strengthened by further deliveries of Hurricanes. On 2 February, No. 135 Squadron received its first very own aircraft (Z5659 arrived in Rangoon that day), and gained operational readiness within 24 hours. British fighter pilots started to mingle defence with offence, escorting bombers and attacking airfields and other ground targets.

Storey’s Second Fight

Storey gained his next aerial victory on 6 February. When S/L Carey’s aircraft failed to start, “Jack”, flying in Z5659/WK-C, took command of five Hurricanes which were scrambled to intercept a large enemy grouping flying in the direction of Rangoon. Initially, the only means of providing forewarning against air raids were observation stations located along the enemy’s anticipated approach routes, which had been erected already before the war for the American volunteers. But the system did not give the defenders enough time to take off and reach the necessary height. When Storey and his colleagues reached 16,000 feet, they noticed some thirty Japanese fighters from Nos. 77 and 50 Sentai flying at a considerably higher altitude. The enemy attacked with a tactical and numerical advantage. In the chaotic fighting, Storey shot down two Ki-27s and claimed two others as “probable”. He was presented with the opportunity of destroying another aeroplane, however when he got onto the tail of the Ki-27, which did not take any evasive manoeuvres and was therefore an exceptionally easy target, he pressed the trigger only to find that he had run out of ammunition. Storey concluded that his third opponent must have been a complete novice. This could have been because the Japanese, who had been fighting incessantly for nearly two months, were replacing their losses with young, inexperienced aviators. He returned to base with a single hole in the wing skin – the first and, as it turned out, only damage inflicted on Storey by a Japanese fighter during his entire combat career.

Hurricane Z5659/WK-C. Clearly visible unusual roundels on wing uppersurfaces. Photo from forum Britmodeller.

The Rigours of War

The Japanese, probably hoping to avoid the Allied fighters, soon switched to night operations, and the pilots of No. 267 Fighter Wing were tasked with providing a pair of aircraft that would be ready for combat after dusk. Nos. 17 and 136 Squadrons had a few qualified night-fighters. In No. 135 Squadron, only Storey and Carey were trained for this form of combat, and there were times when they would be scrambled twice while on duty. There were no successes, however, and soon attempts at intercepting the nocturnal invaders were abandoned. The constant flying during the day and the enemy’s harrying attacks at night ate away at the pilots physical and mental strength; the scorching heat of the day, the anxious nights, and the constant fighting, made all the more unbearable by tropical illnesses. The aircraft suffered, too. The sun would heat them up so much that incendiary rounds would explode in the ammunition chambers. This issue was resolved by covering the wings with coconut fibre mats and pouring them with water. But other problems soon surfaced, exacerbated by the unavailability of spare parts and necessary tools. Damage that in normal circumstances would have been repaired within a single day eliminated some of the aeroplanes for lengthy periods of time, and sometimes even for good. Since Mingaladon had been reconnoitered in detail by the enemy, dried paddyfields were used as “parking strips”, where pilots would leave their aeroplanes after combat in order to conceal them from aerial attack. But the surfaces of these short and dusty airstrips, scorched by the sun, cracked and created deep fissures which regularly trapped tail wheels, oftentimes damaging them beyond repair. The mechanics then came up with a temporary solution, fitting the fighters with quasi-skids which protected or in some cases replaced the tail wheel (unluckily, I have not come across a photograph presenting this interesting modification). Propeller damage was another common occurrence. But while the lack of spares was not an issue in and of itself, for it would have been easy to cannibalize aeroplanes that were grounded for other reasons, the lack of appropriate tooling rendered such maintenance nearly impossible. To circumvent this problem, technicians commissioned the railway workshops in Rangoon to manufacture a puller, which was then used to rescue a number of fighters that would otherwise have never returned to combat.

Left side view of the Hurricane Z5659. Another example of non-standard roundel on wing uppersurfaces.

Nothing seemed to work as it should. A radar unit which had been set up to strengthen defensive capabilities malfunctioned regularly, and its readings were unreliable. Sometimes, the enemy would appear over the city without being detected on its screen. And if the unit’s operators did actually observe an incoming cluster, they were frequently unable to determine its height or course. Soon, the advances made by the Japanese Army forced the defenders to abandon the observation stations, which left the poorly functioning radar as their sole early warning system.

Burma’s Turn

Following the Fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, the Japanese could shift their attention to crushing Allied resistance in Burma. The British started to prepare for the evacuation of military personnel and civilians from Rangoon. Orders were given for the aerial contingent to move to Akyab airfield, located closer to the border with India. The city of Moulmein capitulated already on 18 February. The situation in Rangoon quickly became critical, even though following the bloody battles of the first week of February the Japanese Air Force had ceased attacks against the airfield used by No. 267 Fighter Wing. As a result, Storey did not have a chance to increase his kill tally. The pilots did carry out escort flights for the Blenheims, but from 6 February they met no opposition in the skies. The first engagement occurred only on 23 February, when six Hurricanes encountered a reconnaissance aircraft convoyed by six Ki-27s from No. 50 Sentai. Carey quickly shot the aeroplane down, while a few minutes later our protagonist, once again flying in Z5659, got onto the tail of one of the fighters and dispatched it with ease. The Japanese pilot, clearly inexperienced, did not notice the approaching danger and failed to take any evasive action.

Hurricane Mk.IIb trop Z5659/WK-C, 135 Squadron RAF, Mingaladon, Burma, February 1942. P/O William John ‘Jack’ Storey. Artwork by Zbyszek Malicki, Arma Hobby.

Finally, the time came to leave Mingaladon. The majority of the air and ground crews of No. 17 Squadron moved to Akyab airfield. On 28 February, the American volunteers from “Hell’s Angels” left for Magway. The pilots and aircraft of No. 135 Squadron remained for the defence of Rangoon.

On 1 March, Storey was officially promoted to Acting Flight Lieutenant; on the same day, he had the most dangerous experience of his career. His unit was tasked with strafing the Japanese forces that were making a decisive push in the direction of Rangoon. Accurate ground fire pierced his oil tank, forcing Storey to attempt a return to base. But he had 90 miles to fly – mostly over the sea – in an aeroplane whose engine could seize at any moment. Worse still, the Hurricane’s desert camouflage made it stick out like a sore thumb; a defenceless target brilliantly silhouetted against the sea. Years later, he recalled this flight as the most terrifying and agonising episode of his wartime odyssey.

On 7 March, Storey finally left Rangoon for Akyab. Three days later, on 10 March, he was granted leave. Upon returning from Burma, he weighed only 44 kg.

His aeroplane, whose appearance we have recreated on the basis of the attached photographs, also enjoyed its fair share of luck. After being evacuated to Calcutta, it was repaired and returned to No. 135 Squadron, with which it was still serving in December 1942.

This is the first part of the story of the little knight, “Jack” Storey, and his Hurricane Z5659. The second instalment, as I hope, will be written once we turn our attention to determining the paint scheme and markings of the aircraft which he used in 1943 – AP894/C.

English translation by Maciek Zakrzewski

Sources:

- Lex McAulay “Burma Hurricane Ace: Flight Lieutenant Jack Storey” Banner Books 2015 link

- Norman Franks “RAF Fighter Pilots Over Burma”, Pen & Sword Books Ltd 2013 link

- Jack Storey interview record, 2003, link.

- Operations Record Book 135. 136 and 17 Squadron

You may be interested also:

- Buy Hurricane Mk IIb trop kit with Jack Storey markings in Arma Hobby webstore

Huragany nad Birmą – działania bojowe 113 dywizjonu RAF 1944-45

Model maker for 45 years, now rather a theoretician, collector and conceptual modeller. Brought up on Matchbox kits and reading "303 Squadron" book. An admirer of the works of Roy Huxley and Sydney Camm.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski