Sam Folsom was one of the last living World War II veterans. It is with great regret that we learned he passed away on November 13, 2022, one day after the 80th anniversary of the victory over Japanese bombers near the Guadalcanal. During his lifetime, he was first and foremost a pilot with the United States Marine Corps. At Guadalcanal, he fought on the F4F-4 Wildcat with Marine Fighting Squadron 121 (VMF-121). Later, he flew F4U Corsairs over Okinawa, and then in Korea, providing cover for the Marines at Chosin Reservoir. He became more widely known long after the war, in 1998, when he foiled a bank robbery.

Inspired by Charles Lindbergh

Similarly to Joe Foss, Sam Folsom became interested in aviation after hearing of the exploits of Charles Lindbergh. Initially, he volunteered for the Navy, and, following training, was posted as an officer to the Naval Reserve. Next, he tried to get a transfer to the United States Marine Corps Aviation, but in order to commence training he was forced to resign from his Navy officer’s rank. He ultimately got his wish and was sent to Jacksonville Naval Air Station (Florida), where as a cadet he learned to fly the Grumman F3F-2 biplane. While he was there, on 7 December 1941, America entered the Second World War. Promoted to the rank of second lieutenant in the Marine Corps Aviation Reserve, he was finally posted to a front line unit in March 1942. This was Marine Fighting Squadron 121 (VMF-121), which was being formed in Kerney Mesa near San Diego, California. The conditions of training were very difficult, mainly due to the lack of aircraft: the entire group of pilots, totalling 80, had only 20 F4F-3/4 Wildcats between them. Before setting off to war, Folsom managed to gain no more than 25 hours flight time on the fighter (in all, he had some 250 hours flying experience). Many of his colleagues had even less luck, however, having trained for only a dozen so hours on the Wildcat.

We were absolutely, positive, greenhorns.

Heading for Guadalcanal

VMF-121 was sent as a reinforcement for the Marines defending Guadalcanal in the Solomon Archipelago. The island, upon which the Japanese had been building an airfield that would have directly threatened communications between the USA and Australia, was finally seized by the Americans in August 1942. But the Marines’ positions were regularly attacked by enemy aerial forces flying in from bases in the Bismarck Archipelago, which were a few hundred miles distant. The Imperial battleship fleet brought in supplies and pounded the formerly Japanese airbase on Guadalcanal, now known as Henderson Field, with its artillery. The American aerial contingent was under immense pressure and suffered heavy losses. Worse still, two months passed before VMF-121 even reached the island.

The squadron’s pilots, sailing to the South Pacific on board a luxury transatlantic cruise ship, took great delight in the voyage. After arriving in Samoa, they had a spell of rest and later resumed their journey to Nouméa on New Caledonia. Once there, they collected their new aircraft and embarked on the escort aircraft carrier USS Copahee, from which they were to finally reach their destination. Folsom’s initial attempts at taking off from the vessel, made on 29 September 1942, were rather unfortunate, as he had difficulty maintaining even flight after being rapidly ejected by the ship’s catapult. The two pilots who followed immediately after him crash-landed in the ocean. Second Lt(N) Elliott from VMSB-241 perished, while his SBD-3 Dauntless (BuNo 06535) was lost. His colleague from VMF-121, Second Lt(N) Bob Simpson, was saved (F4F-4 BuNo 11729).

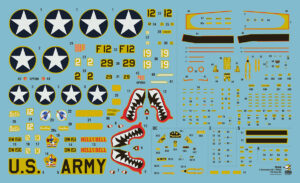

Cactus Air Force Deluxe Set – Wildcat i Airacobra nad Guadalcanal – malowania z zestawu

Between 7 and 11 October, the aircraft carrier sailed near to Guadalcanal and catapulted 20 more of the unit’s Wildcats; all landed safely on the island. Folsom reached Guadalcanal by a different route, along with a group of a dozen or so pilots on board a C-47 transport. The landing, on 8 October 1942, took place in a rainstorm. At the time, not all of the aircraft had reached their destination, and so the first task of the new arrivals was to dig themselves foxholes for protection against enemy bombing. Two days later, the final group of aviators flew in on their Wildcats. For the next two months, they faced the high humidity and assorted other “attractions” of the tropical climate.

Folsom was detailed to a section comprising eight fighters under the command of the unit’s leader, Duke Davis. The second section was led by Joe Foss, who went on to become the squadron’s most famous ace. The unit had 40 pilots in total, but only 20 survived the next sixty days – three or four were unable to cope with the rigours of service, while the rest perished.

VMF-121 pilots on Guadalcanal, first from left: Sam Folsom. Photo: Sam Folsom via John Mollison

Fighting the Japanese

Sam Folsom’s first aerial combat laid bare the problems of training and equipment. An attempted intercept of twin-engined G4M Betty bombers at a height of 30,000 feet (approximately 9,000 m) was unsuccessful. The grease used to lubricate the Wildcat’s machine guns froze at the altitude and the weapons could not be fired.

His combat flights over the next month were just as ineffective. On 11 November 1942, during the famous battle with Japanese aircraft which were attacking American ships delivering supplies to the island, Folsom managed to damage one Zero, which, however, failed to explode – as many of these fighters regularly did. Although hit and belching smoke, the aeroplane made off, and since no point of impact with the ocean was noticed, it was reported as a “probable”.

Sam Folsom (Wildcat No. 29) shots down G4M-1 Betty, November 12th, 1942. In foreground: P-400 Airacobra from 67th Squadron USAAF. Artwork by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Only on 12 November did Sam finally manage to shoot down an enemy aircraft, a G4M Betty bomber, and then quickly downed another. When his patrol of eight Wildcats, together with eight P-39 Airacobras, was waiting at high altitude, Captain Joe Foss observed a group of bombers from 705th “Misawa” Kokutai flying well below them. Foss’ battle order was laconic, to say the least: “Let’s go gang”. His pilots swooped down on the enemy with a vengeance. Folsom attacked a section of bombers. But the first aircraft was set on fire by another Wildcat. Our hero tried his luck with another of the bombers, and, after hitting the pilot, the aeroplane plummeted into the sea. The third aeroplane from the enemy section required a bit more work.

As I came up astern, he began to skid from side to side, although he was just above the surface of the water. Joe Nip in tail gun kept firing and each time the plane skidded, the side gunners would give me a blast. Then his right engine sent out a plume of white smoke and as it did, his tail smacked the water, sending up a cloud of spray only to lurch out the spray and fly on. Closing in again, I peppered him with the last my ammo. This time I was rewarded by seeing him hit the waves for keeps – right wing first, the plane catapulted into the sea.

Later, while returning to base, he was jumped by three Zeroes. Making every effort to avoid being shot down, Folsom somehow managed to escape his attackers – although after making it home he found that a 20 mm cannon shell had made a hole in his wing. The flap was hanging limply, which explained why he nearly rolled over during landing.

Sam Folsom at his Wildcat, with just repaired damages after encounter with Zeros on November 12th, 1942

The first sea battle for Guadalcanal, during which American surface vessels repulsed a Japanese attack, took place in the night from 12 to 13 November 1942. In the morning, Captain Joe Foss sent Folsom to reconnoitre the location of the remnants of the enemy fleet. His choice of pilot was based on Sam’s considerable experience, which – as Foss hoped – would give him a better chance of success. During the take-off, Folsom’s wingman somehow got lost, and he was forced to carry out the perilous mission on his own. Beyond Savo Island, he found a damaged battleship accompanied by destroyers:

She was a tremendous vessel – larger I believe than any other I had ever seen. There was no mistakenly the pagoda mast with its irregular decks jutting out at every angle. Only one stack was visible, although smoke was rising just forward the main mast, and it is possible that her after-stack had been blown off during the night action. If she was a Konga class, as was thought at first, her after-funnel was gone.

After returning to base, he reported that he had sighted a Kongō class battleship, however later it was erroneously determined that this was a secretly built ship with a displacement of 45,000 tonnes (but the Yamato class, which tallied with the description, had a much greater displacement). In reality, this was the battleship Hiei, a Kongō class vessel. It was sunk on the same day in a mass bombing raid carried out from Guadalcanal. Folsom flew in the escort of the American assault group, and also attacked the enemy ships using his machine guns, trying to make light of the withering anti-aircraft fire put up by the Japanese. Returning to base, he encountered a dozen or so Zeroes which eagerly chose his lone Wildcat for target practice. He finally managed to lose the enemy in the clouds, however his aeroplane was damaged and there was still a long way home.

Battleship Hiei manouvers under air attack, November 12th, 1942 near Savo island north of Guadalcanal. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Over the next few days, the Americans succeeded in gaining the upper hand in the fight for Guadalcanal, among others by defeating Japanese attempts at strengthening their forces on the island. The enemy lost a few important vessels and 11 fast transport ships, and practically lost the ability to provision their garrison. Next, Folsom was tasked with locating pilots who had ditched in the ocean. His first “target” was Colonel Bauer, the commander of the Marine aviation group. Foss and Folsom flew off as escorts for a Grumman J2F Duck flying boat, however they did not find the airman before dusk.

Another fighter and myself, together with a “duck”, left to search for the Colonel who had been last seen swimming towards shore which was at last twenty miles distant. Darkness closed in before we reached the area – blotting out everything in its pitch blackeness. In the vain search that followed the flight became separated. After spending some time flying low over the surface in hope that I might, by sheer luck, spot him, I realized the hopelessness of the mission and headed home. That proved a lonely trip – one hundred miles from Guadalcanal’s fighter strip in utter blackness with only dead reckoning to go by. When the tip of the Island finally appeared, my relief was beyond explanation.

The second search mission, this time successful, was to locate the crew of a B-17 Flying Fortress that had been shot down while returning from an attack on Rabaul. The flight was performed by three Wildcats equipped with additional long-range fuel tanks. When the fighting for Guadalcanal eventually drew to a close, VMF-121 was sent away for rest. Foss’ section was transferred to Australia, while Folsom and his comrades ended up in Faleolo on Samoa, where they were joined by VMF-111.

F4F-4 Wildcat No. 29 taking off with underbelly fuel tank. Visible in the background P-38 Lightning fighters just arrived to Guadalcanal, November 1942. It may be Sam Folsom’s last mission, search-and-rescue of downed B-17 crew, november 15th, 1942. Unfortunately we weren’t able to confirm it before Sam Folsom passed away. Maybe someone from our readers can confirm that?

Resting After the Battle

Away from the front line, the American pilots finally had the opportunity to recuperate. And Sam found time to restore his personal aircraft – the Wildcat with side number “5” – to near perfect condition, and also decorated it with an image of Popeye in Marine Corps gala uniform. Symbols denoting Folsom’s three kills were painted on the fuselage side. An interesting accent are the white stripes next to the stars, which were introduced in the beginning of 1943 and added in the unit to the previously applied markings.

Sam Folsom and his Wildcat “Popeye” from VMF-111, Samoa, early 1943. Photo: Sam Folsom via John Mollison

Sam Folsom at his Wildcat cockpit, Samoa in early 1943. Photo: Sam Folsom via John Mollison

But this was not the end of our hero’s military service. In 1945, he was posted to a pioneering night-fighter unit, VMFN-533, which operated from Okinawa and flew the F-4U-2N Corsair, and later took part in the Korean War, where he supported the Marines during their withdrawal from Chosin Reservoir. He left the service in 1960 in the rank of lieutenant-colonel. In 1998, he foiled a bank robbery by calling the police and helping overpower the assailant. He is one of the last living pilots of the United States Marine Corps from the Second World War.

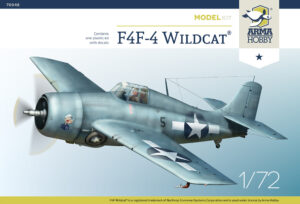

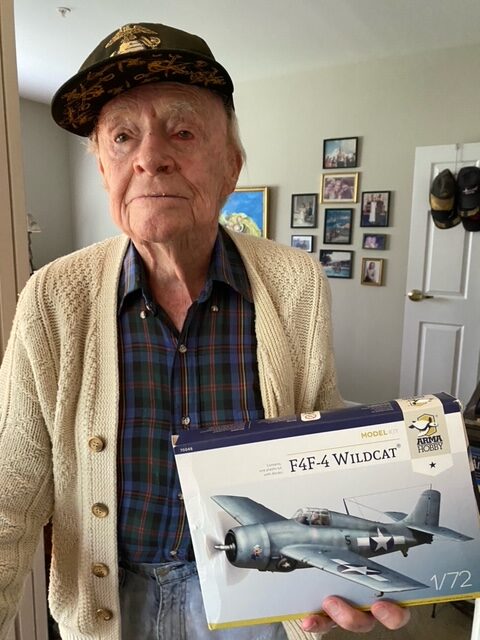

Sam Folsom with Arma Hobby Wildcat kit, spring 2022. Photo: Gerrit Folsom

- I would like to extend my special thanks to Ms Lindsey Folsom and Mr Gerrit Folsom, Sam Folsom’s children, and also to Mr John Mollison for their help in the writing of the article.

English translation by Maciek Zakrzewski.

Literature

- Folsom, Samuel. Wildcat Squadron, a memoir manuscript written during his period of service on Samoa, 1943

- Doll, Thomas. Marine Fighting Squadron One-Twenty-One (VMF-121), Squadron Signal, Carrolton 1996

- Lundstrom, John B. The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, Naval Fighter Combat from August to November 1942. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2005.

- Mollison, John “Popeye” as flown by Sam Folsom, VMF-121

- Persinger, Ryan, Pfc. He’s One of the Last Living WWII Marine Corps Pilots, Military.com 20 July 2018

- Reed, Patrick. Guadalcanal Fighter Pilot, Leatherneck Magazine, July 2020

- Samuel B. Folsom Collection, Library of Congress link.

You may be interested:

- F4F-4 Wildcat kits with Sam Folsom markings: Link

Modeller happy enough to work in his hobby. Seems to be a quiet Aspie but you were warned. Enjoys talking about modelling, conspiracy theories, Grand Duchy of Lithuania and internet marketing. Co-founder of Arma Hobby. Builds and paints figurines, aeroplane and armour kits, mostly Polish subject and naval aviation.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski