One of the most distinctive representatives of the so-called Greatest Generation – the American generation that won the Second World War – was Captain Joseph Foss, a fighter ace of the US Marine Corps. Toughened by growing up during the Great Depression, he showed great determination to realize his dream of becoming a Marine aviator. Foss was the first American pilot to equal Eddie Rickenbacker’s record tally of kills, dating all the way back to the First World War – an achievement for which he received the Medal of Honor. Read on to learn his story.

A Farmer’s Son from Dakota

Joseph Foss was born in 1915 – just a few years before the generation that would be conscripted en masse during the Second World War. Following his father’s unsuccessful business ventures, his family took up residence in Sioux Falls in South Dakota. Joe was an active and ambitious child. Growing up on a farm, he developed an appetite for hard work, and practised shooting on a regular basis.

Foss family house in Sioux Falls, photo: Chicago Tribune.

Three events shaped his personality:

- In 1927, he saw Charles Lindbergh, the conqueror of the Atlantic, when the famed aviator toured the United States in his aircraft, “Spirit of St. Louis”.

- At the beginning of the 1930s, Sioux Falls hosted a Marine Corps squadron commanded by Captain Jerry Jerome. It was the first time that Joe, then in his mid-teens, had seen a formation of aircraft in flight. From that moment on he knew that he had to become a Marine Corps pilot.

- In 1933, when he was eighteen, his father perished in a car accident. Over the next few years, he worked hard to gain an education and gradually learned to fly, supporting himself with various odd jobs. When the droughts of 1935 and 1936 destroyed the family’s crops, he became its main breadwinner. In order to pay for college tuition, Joe sold his brother a plot of land that he had inherited from his grandmother and invested the entire payment – 1,000 dollars – into his studies.

While in college, he qualified as an aviator and also enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve, and this helped him receive a posting with the Corps.

Too Old to Be a Fighter Pilot

Too Old to Be a Fighter Pilot

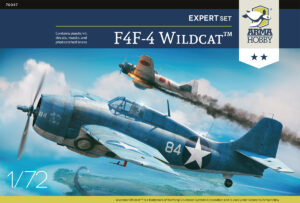

Joe Foss was not initially considered for fighter pilot training, for although he was a very good flier, his age clearly exceeded that of the preferred candidate profile. In March 1941, after receiving promotion to Lieutenant and winning his pilot’s wings, he became an instructor at the base in Pensacola. It was while he was serving there that he received the shocking news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He was then transferred to Marine Observation Squadron 1 (VMO-1) in San Diego with effect from 1 January 1942. While there, Foss managed to get some flying time on the F4F-4 Wildcat, and on 1 August he was appointed deputy commander of Marine Fighting Squadron 121 (VMF-121), which was being formed in Kearney Mesa. A month later, the unit began its trek to the South Pacific. Its destination was a little-known island by the name of Guadalcanal.

Photo: Joseph Foss promoted to Lieutenant. From the book “Flying Marine…”

The Battle of Guadalcanal

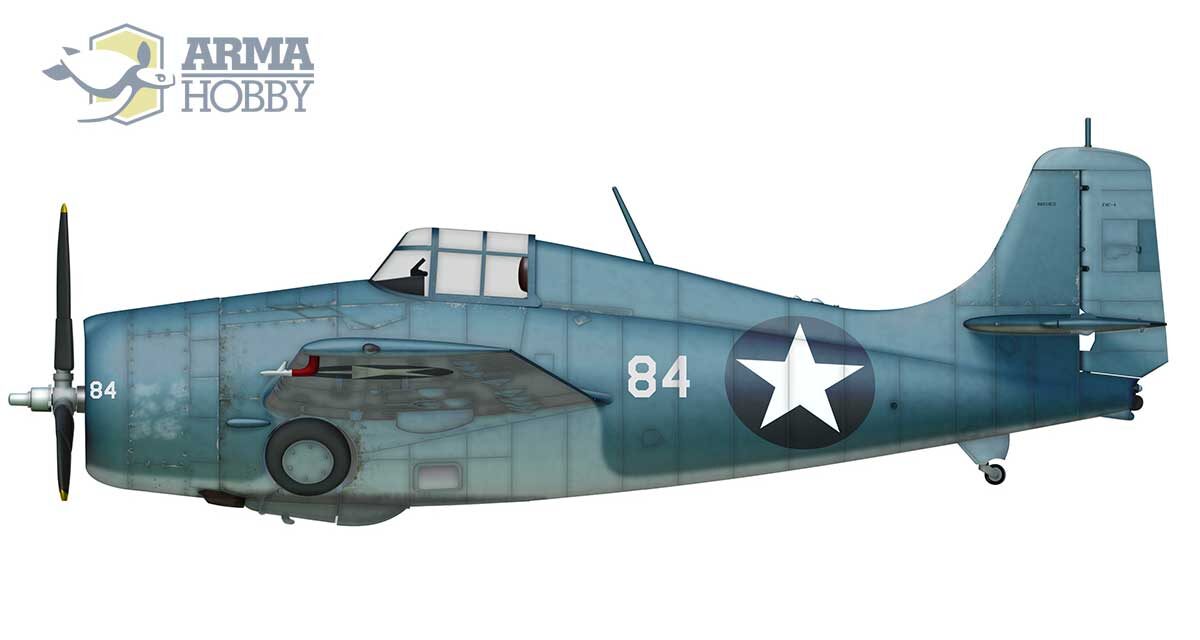

Guadalcanal is a medium-sized island located in the south-easternmost part of the Solomon Archipelago, which at the time was an Australian mandate. In the summer of 1942, the Japanese occupied the island and started building a large airfield; clearly, this would have posed a serious threat to communication lines between Australia and the USA. What came to be known as the Battle of Guadalcanal commenced on 7 August 1942, when the 1st Marine Division carried out an amphibious landing. The unfinished airstrip was quickly captured, and the enemy’s first counter-attacks were successfully repulsed. Unfortunately, over the next few days the situation deteriorated rapidly. Having been routed at the Battle of Savo Island, the supporting American naval task force withdrew in order to avoid further losses. The Marines were left to fend for themselves. On 20 August, USMC squadrons started arriving on Guadalcanal, however they had considerable difficulty with repelling the Japanese. Groups of enemy aircraft flew in daily from the base on Rabaul, located in the Bismarck Archipelago, and attacked the American defences and shipping lanes with a vengeance. Despite suffering heavy losses, the Marine pilots, assisted by U.S. Navy airmen, started to fight back.

Battlefield between Guadalcanal, New Guinea and Rabaul, red circles indicates the most important air bases. Map: Wikimedia Commons.

The “Cactus Air Force”, as the aerial units stationed on the island were called, had the advantage of operating close to the battlefield. The few hundred kilometres separating the Japanese from their target gave the defenders some time to prepare for assaults. Furthermore, Australian Coastwatchers, dispersed in hiding throughout the archipelago, gave forewarning of enemy aircraft and ships heading towards Guadalcanal.

Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, photo: Wikipedia.

Military service on the island had numerous “attractions”, and enemy aeroplanes were just one of the challenges faced by the Marine aviators. At night, the Japanese would send in transport vessels of the “Tokyo Express” with supplies for their troops, and, as they were unloading, their escorts would shell the airfield with their main batteries. The accurate fire laid down by the enemy cruisers and battleships destroyed aircraft and made holes in the runways, forcing the defenders to wait out the nights in foxholes dug around their tents. Whereas during the day, in addition to the air raids, the aircrews and airfield personnel were harried by snipers. There were other nuisances, too: a constant shortage of food, tropical sicknesses, poisonous reptiles, and vermin. The defenders were constantly threatened by counter-attacks, launched by enemy infantry with the objective of neutralizing the airfield.

Marines airmen tents on Guadalcanal in 1944. Photo:

Many pilots were shot down or suffered mechanical failure over areas occupied by the Japanese, and, having landed or parachuted to safety, had to force their way through the jungle to reach friendly lines. Of great help was the assistance of native residents and the ever-ready Coastwatchers, who quickly smuggled downed aviators back to their base in secret from the enemy. These “trips” were often a welcome break from the difficulties of service – a period of rest during which the exhausted pilots could feast on fresh meat, eggs and fruit.

VMF-121 Arrives on Guadalcanal

Marine Fighting Squadron 121 (VMF-121) arrived on the island in October 1942, shortly before the fighting reached a turning point. Towards the end of the month, the adversaries fought the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, while in the first two weeks of November a series of fleet encounters took place along the Japanese supply routes. It was then that the Americans finally gained the upper hand.

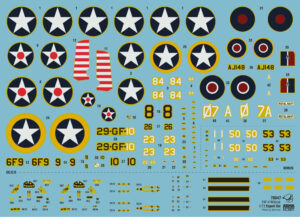

The squadron’s voyage from San Diego lasted more than a month. After a short stop over on New Caledonia, where the pilots practised taking off from the aircraft carrier USS Copahee and landing on the island, the unit finally received orders to transfer to Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. The ship duly left New Caledonia and over the next few days individual echelons of the squadron departed its deck. Captain Joe Foss was in charge of a section of eight fighters that would later become known as Foss’ Flying Circus. His echelon – the last of the squadron – landed after a three-hour flight on 9 October 1942. Initially, his aircraft carried the number “13”, however this was changed to “53” in order to avoid confusion with that of Captain Marion Carl, an ace from VMF-223. Foss’ strong points were his maturity (a by-product of age) and relative experience, for he had logged 1,400 flying hours before being sent into combat. Now, he was faced with his greatest challenge.

As he himself recalled, the pilots of VMF-121 had spent the journey to Guadalcanal discussing tactics, and their theoretical findings were soon put to the test. Their colleagues, who had already been fighting the Japanese for more than a month, knew best how to play the game. Lieutenant-Colonel Harold “Indian Joe” Bauer from VMF-212, the mentor of the Marine pilots, advocated fighting as a team, utilizing the structural weaknesses of the Zero fighter, and entering combat aggressively and withdrawing skilfully if it was found that the enemy enjoyed a numerical advantage.

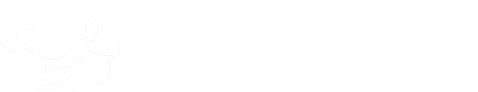

Wildcat from VMF-121 on Guadalcanal.

Wildcat from VMF-121 on Guadalcanal.

The First Fight

On 13 October at noon, the Japanese surprised the Americans while they were still on the ground. There had been a lapse in communication and reports of the approaching enemy were not received in time. Following an emergency take-off, Joe Foss failed to make contact with the raiders, however all this changed during his second sortie. Dazed by the sudden explosion of a Zero at which he had just fired, he felt his hair stand on end and his mouth run dry. Being pursued by a group of enemy fighters, he turned back to the airfield, landing with his engine nearly seized and a part of the oil cooler shot off. At night, two battleships of the Imperial Japanese Navy – Kongo and Haruna – carried out the heaviest shelling that the airstrip had yet experienced. Although Marine Scout Bombing Squadron VMSB-141 suffered serious losses, and the fuel depot was utterly destroyed, the next day VMF-121 still managed to put up 16 aircraft. During the second day of fighting, 14 October, Joe Foss shot down another Zero, but the unit lost three aeroplanes. On 18 October, having downed two Zeros and one bomber, he became an ace, with five officially recognized kills to his credit. This combat, however, was only a prelude to a series of land and sea battles that were to rage from 24 to 27 October. Over the next week Foss nearly tripled his score.

Wildcat Versus Zero

In his book, Joe Foss described the differences between the combatants’ aircraft and pilots (see the recommended reading list at the end of the article). Despite suffering heavy losses, there was no denying that the Japanese aviators were well-trained and flew exceptionally manoeuvrable fighters, the main weak point of which was a relatively frail structure. Further, neither the A6M Zero nor the bombers – including the G4M Betty, the mainstay of the long-range attack squadrons – had any armour plating. In dogfights, the Wildcats, which frequently flew in mixed formations with P-39 Aircobras or P-38 Lightnings of the USAAF, made full use of their superior firepower and the reconnaissance data at their disposal. The Americans’ preferred tactic was to wait for the enemy in the air, and, while attacking, aim for the fuel tanks. In the Zero, these were located near the point of connection of fuselage and wing. According to Joe Foss, a hit in this location usually resulted in the immediate explosion of the fighter – and the death of its pilot. The Wildcat on the other hand was considerably more resistant to gunfire, so much so that Joe Foss recalled only one instance where an F4F caught fire. The F4F-4 could be rendered ineffective only by damaging its engine or hitting the pilot (or if the latter expended all of his ammunition). The Zero could not keep up with the Wildcat in dives, spins or rapid turns performed at high speed.

A6M2 Zero fighters in Rabaul, 1942. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

On Guadalcanal, enemy aircraft that exploded or crashed into the sea or land were registered as kills. But aeroplanes that were trailing smoke – so-called smokers – were often abandoned in order to attack other targets or provide help to colleagues. It was assumed that they had actually been destroyed, however they were not recognized as aerial victories due to the lack of confirmation.

Basically, the unique tactical situation favoured the Americans, who fought the Japanese in proximity of their base, while the latter had to fly a few hundred miles just to get to the battlefield. The Marine Corps and U.S. Navy furthered their advantage by organizing a steady stream of replacement pilots (and saving many of those who were shot down) and sending fresh units into the fight – something the Japanese could not hope to match. In this battle of attrition, their squadrons, including the elite Tinian Kokutai, lost their best pilots and declined in strength. Foss, however, had a healthy respect for the enemy, advocating constant vigilance and seconding Bauer’s recommendations:

- “We have a saying up at Guadalcanal, if you’re alone and you meet a Zero, run like hell because you’re outnumbered.”

- “When you find yourself all alone out there, head for home. (…) Look, when I was all alone, I scooted for home. I’m still around. The guys who fought themselves are dead”.

Cpt. Joseph Foss, USMC, in speach to the RAAF 1st wing pilots, Sydney, December 1942.

Cpt. Joseph Foss shots down Zero fighter over Salomons. Artwork by: Piotr Forkasiewicz.

The Onslaught Against Henderson Field

On 24 October, the Japanese Army launched an attack from the jungle on the positions defending Henderson Field; it was repulsed by 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, and 3rd Battalion, 164th Infantry Regiment (U.S. Army). But the air raids launched from Rabaul continued unabated. The day before, Joe Foss shot down four Zeroes, while two days later he improved his score by downing five Zeroes within the space of twenty-four hours! He destroyed two during his first sortie, and two more during the next. Then, while returning to base, he spotted two other Zeroes lying in wait for a lone Wildcat. Since he was too far away to intervene, he shouted out a warning over the radio. The pilot escaped by executing a rapid manoeuvre, however Foss – jumped by yet another pair of enemy fighters – did not see this. Fighting for his life, he shot down one of the assailants and landed, his ammunition almost exhausted. Over the next three days (25–27 October) the opposing aircraft carrier groups fought what has come to be known as the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. The Japanese gained a tactical victory, sinking the USS Hornet and damaging the USS Enterprise. They too, however, suffered losses in men and materiel, while their damaged aircraft carriers did not dare approach Guadalcanal for fear of attack from Henderson Field, which was still operational.

One of Joe Foss aeroplanes, white 84. Photo: Department of Defense.

Foss Gets Shot Down

On 7 November, two sections of Wildcats flew 150 miles north of the island in order to attack a grouping of Japanese vessels. The seven Wildcats led by Joe Foss spotted a formation of six Mitsubishi Rufe float-plane interceptors and immediately launched an attack. Joe duly shot one down, but the dogfight had placed him at the end of his section. When the Americans finally reached the enemy warships and were about to strike, he looked behind him and saw a lone Mitsubishi Pete reconnaissance float-plane. He quickly shot it down, however his own aircraft was hit by the rear gunner. A bullet penetrated the cockpit fairing, scaring Joe out of his wits. But the Wildcat remained airborne, so after a while he calmed down. He soon noticed another Pete and shot it down too. By this time, having lost sight of his section, he decided to return to base. However, he made a navigational error and flew the wrong way in a squall, finding himself over an unknown body of water. Suddenly, without any warning, the engine sputtered and stopped. There was no choice but to splash down. The fighter started to sink even before Foss had managed to unbuckle his safety belt. His Mae West filled with air and pulled him upwards, making it impossible for him to reach the strap that was holding his ankle. The Wildcat continued to take on water, dragging him down. The pilot thrashed around, choking – he could not free his leg. Finally, the aircraft let him free. Bobbing in the water in the gathering darkness, he began resigning himself to his fate. But during the night he saw a boat circling around, its searchlight penetrating the blackness. He hunched up, fearing that he would be captured by the enemy. Luckily for him, however, the vessel was manned by a planter and some natives. When the exhausted aviator finally came ashore, it turned out that he was on Malaita, an islet where escapees from islands occupied by the Japanese had sought refuge. Overjoyed by the warm welcome, he gorged himself on the delicious local fruits, many of which he had never tasted before, and began hoping that his exotic “holiday” would last just a while longer. But it was not to be. Already the next day he was collected by a PBY Catalina from Guadalcanal and returned to his squadron. On 9 November, he received his first decoration, the Distinguished Flying Cross, which was awarded to him personally by the commander of naval forces in the South Pacific, Admiral Halsey.

Rearming Foss’s Wildcat fighter (white 84).

Guadalcanal – The Turning Point

The battles fought for Guadalcanal in October had not proved decisive, and the combatants were preparing for yet another confrontation, which, as it turned out, was to prove the turning point of the campaign. In preparation, reinforcements from the Japanese Army’s 38th Infantry Division were sent to the island. The Imperial Fleet provided 11 fast transport vessels accompanied by an imposing array of battleships (the Hiei and the Kirishima) and assorted smaller ships. Their plan was to bombard Henderson Field during the night from 12 to 13 November, and then repeat the strike and land troops in the night from 13 to 14 November. The Americans sent their own transport of infantry and supplies under the escort of a cruiser group. The aerial part of the battle was fought by the “Cactus Air Force” and the naval aviators from the USS Enterprise on the one hand, and the Japanese squadrons from Rabaul on the other.

P-400 of the 67th Fighter Squadron USAAF on Guadalacanal, 1942.

„Let’s go gang”

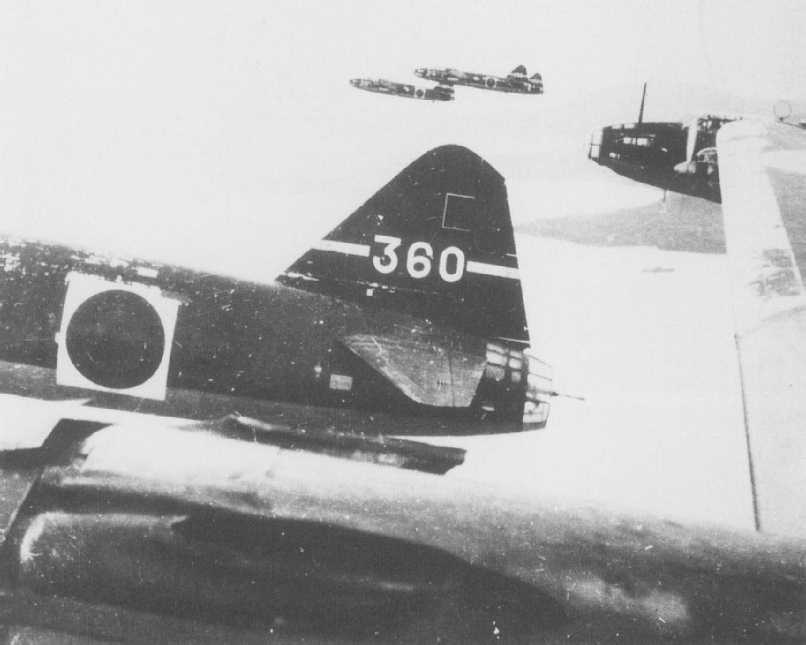

While the American reinforcements were being disembarked on 11 November, they were attacked by aircraft from the carrier Hiyo, which had first been redeployed to the airstrip of Buin. The “Cactus Air Force”, supported by artillery fire from the anti-aircraft cruiser USS Atlanta, repelled the assault without any damage to American surface vessels. The Japanese did, however, succeed in jumping and shooting down a section of Wildcats from VMF-121, losing only two Zeroes. The most epic encounter of the fighting in defence of Guadalcanal occurred on the very next day. A group of 17 Betty bombers armed with torpedoes and escorted by 30 Zeroes was spotted by Paul Manson, a Coastwatcher on the island of Buin, at 13:17. An hour or so later, the enemy force appeared over Florida, an island right next to Guadalcanal. Joe Foss and eight Wildcats from VMF-121, together with eight P-39s, were lying in wait at a height of 29,000 feet, while a section of eight fighters from VMF-112, commanded by Major Paul Fontana, was climbing to 5,500 feet. Seeing that the enemy were at a lower altitude, Foss gave a laconic order: “Let’s go gang”. But the sudden dive had an unexpected effect on the American aeroplanes: the rapid loss of height caused their windscreens to frost up, and one of the P-39s, its pilot blinded, crashed into the sea. Foss lost his cockpit canopy and the fuselage side panels, which were ripped off by the rushing air. When, however, they caught up with the bombers, all hell broke loose. Only a few G4M Betties managed to launch their torpedoes. Eleven were shot down, while the remainder suffered damage beyond repair and were written off after landing. The Americans also destroyed seven Zeroes, themselves losing three Wildcats and one P-39. In addition, the cruiser USS San Francisco was slightly damaged when an enemy aircraft, on fire, hit its rear mast. Once the attack was repulsed, the troops disembarked without further hindrance. During the fighting Foss accounted for two Betties and a single Zero, thus bringing his kill tally for just under one month to the imposing figure of 22. As a matter of note, the decimated bomber unit was 705 “Misawa” Kokutai, which had sunk the HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse in December 1941.

Formation of the G4M Betty torpedo bombers from 705 Kokutai after the battles of Guadalcanal, 1943. Photo: Wikipedia.

Two Night Battles Near Guadalcanal

When dusk fell, the first night battle of Guadalcanal – the first encounter of what came to be known as the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (12–15 November) – was fought close to the location of the day’s aerial combat. The Japanese battleships Hiei and Kirishima were ordered to bombard Henderson Field but were intercepted by an American cruiser group. Both sides incurred heavy losses, while Japanese deliveries of supplies to the island were halted for twenty-four hours. The next day, the “Cactus Air Force” launched a ferocious assault on the enemy battleships. The attack was led by TBF Avenger torpedo bombers and SBD Dauntless dive-bombers, supported by the machine-gun fire of the Wildcats. The Hiei, heavily mauled the previous night and deprived of aerial cover, was sunk.

Cpt. Joseph Foss Aeroplanes in VMF-121

Cpt. Joseph Foss flew during Guadalcanal campaign at last three aeroplanes. na kilku samolotach. Only one of them is known from photos: Wildcat No. 84.

Cpt. Joseph Foss flew during Guadalcanal campaign at last three aeroplanes. na kilku samolotach. Only one of them is known from photos: Wildcat No. 84.

His first F4F-4, No. 13, was remarked with 53, and according to his relation was serviceable in January 1943. Another one was Wildcat No. 50.

Artwork by: Zbyszek Malicki.

The Japanese withdrew, however fresh naval forces were already approaching the island, quickly drawing the attention of the USMC aviators and their colleagues from the USS Enterprise. The group of four Imperial Navy cruisers and its escort were attacked nearly all the way to Guadalcanal, but nevertheless pressed ahead with great determination. During the night from 13 to 14 November, the enemy force shelled Henderson Field with its main batteries, and then withdrew. In the course of the retreat, as light began to dawn, one of the cruisers was sunk and one damaged. Also sunk were seven transports carrying supplies for the Japanese garrison on Guadalcanal. The USMC pilots launched successful attacks against the enemy surface vessels at a distance of some 100 nautical miles off the island. Tragically, they also incurred a great loss when Lieutenant-Colonel Harold Bauer was shot down. Joe saw him bobbing in the water, but the rescue parties that were sent out the next day were unable to find him.

Before the search commenced, however, the combatants fought the final encounter of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. Yet another enemy task force, with the battleship Kirishima at its core, attempted to repeat the bombardment of the previous night. It was faced by the last reserves that the U.S. Navy had near this part of the island: the battleships USS Washington and USS South Dakota, which, together with an escort of destroyers, had left the USS Enterprise battle group and approached Guadalcanal. In the chaotic night fighting, the Americans gained the upper hand and repulsed the Japanese surface vessels. The four remaining enemy transports sailed to shore and quickly began unloading. The infantry managed to disembark, however an early-morning attack by the “Cactus Air Force” destroyed the ships. All of the ammunition and supplies were lost. On that day Foss shot down his twenty-third enemy aircraft, a Mitsubishi Pete float-plane.

Abandoned on Guadalcanal beach Japanes transport ship Kinugawa Maru, November, 15, 1942. Colourised photo: U.S. Navy.

The series of clashes near Guadalcanal between 12 and 15 November 1942 was decisive for the fate of the island. Losses in surface vessels and aeroplanes were not as important for the Japanese as those in fast transport ships. Without them, supplying the island garrison at night, especially when there was no way of countering American air attacks, became extremely difficult. And although the Japanese could still engage in surface actions, their “Tokyo Express” was now forced to ferry materiel using regular warships, which was a much less effective solution in the long run.

A Lull in the Fighting

Exhausted by the incessant combat, the squadron needed rest. Foss himself needed respite more than most, for on 15 November he fell ill with malaria, and went on to lose nearly 20 kg in weight while battling the disease. The group of pilots was evacuated to New Caledonia, where they could finally regain their strength. In December, Foss flew to Sydney, where he completed his convalescence. An altered diet – Australian cow steaks eaten three time a day – helped him immensely. While there, he also took part in numerous meetings, among others (and on a number of occasions) with S/L Clive “Killer” Caldwell, the leading Australian ace, who after a successful period of service in North Africa had returned home to take command of No. 1 Wing RAAF. Foss readily and honestly shared his experience gained during the tough fighting over the jungles of the Solomon Archipelago. Many of those whom he met went on fight in the skies over Darwin in Australia’s Northern Territory.

Start of VMF-121 Wildcats, in the foreground is No. 29 with an early type underbelly fuel tank, in the backgroud is aeroplane with regular underwing fuel tank. Phot taken in January 1943 probably.

Return to Guadalcanal

With the start of the new year, Joseph Foss and his colleagues from VMF-121 returned to Guadalcanal. By then, the Japanese had started a secret evacuation of their garrison. Upon arriving on the island, our protagonist was surprised to find his first aircraft, no. 53, ready for battle. The enemy air raids were less frequent, and occurred mainly at night. The American fighter pilots attacked shipping and ground targets. An increasingly greater number of sorties were directed further away from Guadalcanal. The attacks now focused on Japanese supply lines, which were slowly becoming routes of retreat. On 15 January, Foss and a detachment of U.S. Army P-39 fighters escorted a group of SBD Dauntless dive bombers to targets in the vicinity of New Georgia and Kolombangara, 200 miles north-west of Guadalcanal. The raid was opposed by the newest variant of the Zero, the Model 32, and, in a series of difficult encounters, Joe shot down three of them, thereby becoming the first American ace to equal the record set by Eddie Rickenbacker, the most successful US fighter pilot of the First World War.

After Guadalcanal

Upon returning to the United States, Foss was awarded the Medal of Honour, his country’s highest military award. The ceremony took place on 18 March 1943 at the White House. He spent the next year on a war bond tour, and was returned to active service just before war’s end as the commander of VMF-115, which operated the excellent F4U Corsair fighter. Interestingly, while serving in the Marine Corps he met his childhood idol, Charles Lindbergh. He had no opportunity of raising his tally, however, and a second bout of malaria caused him to be relegated to rear echelon duties, this time permanently. He duly assumed command of Marine Corps Air Station Santa Barbara (MCAS Santa Barbara).

After the war he served in the Air National Guard, was elected Governor of South Dakota, became Commissioner of the American Football League, and was also elected President of the National Rifle Association. He died in 2003.

English translation by Maciek Zakrzewski

Recommended reading:

Doll, Thomas. Marine Fighting Squadron One-Twenty-One (VMF-121). Squadron Signal, Carrolton, 1996.

Foss, Joseph. Flying Marine – The Story of His Flying Circus as Told to Walter Simmons (Illustrated Edition). Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014.

Lundstrom, John B. The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, Naval Fighter Combat from August to November 1942. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2005.

Young, Edward M. F4F Wildcat vs A6M Zero-sen (Pacific Theater 1942). “Osprey Duel 54”. Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2013.

See also:

- Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat model kits in Arma Hobby webstore

Dywizjon „Świętych” – najskuteczniejsza jednostka Wildcatów US Navy

Modeller happy enough to work in his hobby. Seems to be a quiet Aspie but you were warned. Enjoys talking about modelling, conspiracy theories, Grand Duchy of Lithuania and internet marketing. Co-founder of Arma Hobby. Builds and paints figurines, aeroplane and armour kits, mostly Polish subject and naval aviation.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski