The Battle of Midway is commonly recognised as one of the decisive clashes in the history of warfare. It was precipitated by the Japanese attempt at occupying Midway Atoll, the easternmost lying island of the Hawaiian Archipelago. One of the units that distinguished itself in its course was VF-3 Fighter Squadron, commanded by Lt Cdr John “Jimmy” Thach, from the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown.

„Jimmy” Thach

The future commanding officer of Fighting Squadron Three was born on 19 April 1905 in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. In 1923, he entered the United States Naval Academy, and graduated in 1927. Immediately thereafter, he completed a basic piloting course and reported for duty aboard the battleship USS Mississippi. While serving there, he passed another piloting course, completing his first solo flight after only six hours of training on two-man aircraft. In February 1929, Thach was transferred to Pensacola, where he took up a more comprehensive piloting course. Although initially disappointed with his new posting, after some time he “caught the bug”. In 1930, he completed training and was assigned to VF-1B “High Hats” Fighter Squadron in San Diego. While there, he took part in the making of the film “Hell Divers”, starring Clark Gable and Wallace Berry. After two years, he was transferred to a unit of test pilots in Norfolk. He returned to combat units in 1934, and went on to serve in three different reconnaissance and patrol squadrons: VP-9F, VS-6B and VP-5. In June 1939, he was reinstated as a fighter pilot, being assigned to VF-3 Fighter Squadron as Deputy Munitions Officer.

The future commanding officer of Fighting Squadron Three was born on 19 April 1905 in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. In 1923, he entered the United States Naval Academy, and graduated in 1927. Immediately thereafter, he completed a basic piloting course and reported for duty aboard the battleship USS Mississippi. While serving there, he passed another piloting course, completing his first solo flight after only six hours of training on two-man aircraft. In February 1929, Thach was transferred to Pensacola, where he took up a more comprehensive piloting course. Although initially disappointed with his new posting, after some time he “caught the bug”. In 1930, he completed training and was assigned to VF-1B “High Hats” Fighter Squadron in San Diego. While there, he took part in the making of the film “Hell Divers”, starring Clark Gable and Wallace Berry. After two years, he was transferred to a unit of test pilots in Norfolk. He returned to combat units in 1934, and went on to serve in three different reconnaissance and patrol squadrons: VP-9F, VS-6B and VP-5. In June 1939, he was reinstated as a fighter pilot, being assigned to VF-3 Fighter Squadron as Deputy Munitions Officer.

Lt. Cmdr. John “Jimmy” Thach 1942/43, Photo: US. Navy.

In December 1940, Thach was placed in command of the unit. Thach gained a reputation as an excellent marksman and tactician, and soon started training other pilots. Acting in co-operation with his colleagues, he set up a “humiliation team” which examined newly arriving flyers. The aviators of VF-3 were also put through intensive marksmanship training, and six of them received grade “E” (Excellent).

Boeing F4B z VF-1B „High Hats”, early 1930s, Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Thach versus the “Zero”

In the spring of 1941, Thach received an intelligence report detailing the capabilities of the new Japanese fighter – the Mitsubishi A6M “Zero”. The document made dour reading for American pilots. The basic carrier fighter of the US Navy, the F4F-3 (and later the F4F-4), was a good and reliable aeroplane, however it stood no chance in combat with its lighter and more manoeuvrable Japanese counterpart.

Hoping to find a practicable solution, John Thach devoted countless hours to developing a tactic that would at least partially eliminate this imbalance. Once he ironed out the theory, he put it to the test with the help of one his ablest pilots, Butch O’Hare. The tactic has gone down in history as the “Thach Weave”. He also changed the formation used by his squadron from three-plane to the pair.

Following the outbreak of hostilities with Japan, Fighting Squadron Three embarked on the USS Saratoga and headed off to war. Its period of service on the ship did not last long, however, for already on 11 January 1942 the USS Saratoga was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, I-6. The carrier managed to return to Pearl Harbor, and VF-3 was transferred to shore.

Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters from VF-3 flying over Naval Air Station, Kaneohe, Oahu, Hawai, 10 April 1942 r. Aeroplane in foreground is #3976/F-1, flown by VF- 3 commander, Lt.Cmdr. John S. Thach, in backgroung is #3986/F-3, flown by Lt. Edward H. O’Hare. Photo: PH2C H.S. Fawcett. U.S. Navy pfficial photo, National Archives.

Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters from VF-3 flying over Naval Air Station, Kaneohe, Oahu, Hawai, 10 April 1942 r. Aeroplane in foreground is #3976/F-1, flown by VF- 3 commander, Lt.Cmdr. John S. Thach, in backgroung is #3986/F-3, flown by Lt. Edward H. O’Hare. Photo: PH2C H.S. Fawcett. U.S. Navy pfficial photo, National Archives.

VF-3’s first victories

On 31 January, the squadron was embarked on USS Lexington. A few days later, on 10 February, Admiral King ordered the commander of Task Force 11, Admiral Brown, to commence offensive operations in the South Pacific. Brown proposed an attack on the Japanese base of Rabaul. Although his superior consented, the enemy discovered the American fleet before any assault could be launched. At around 10:00, the USS Lexington’s radar operator observed an unidentified aircraft; as it soon turned out, this was a Kawanishi Type 97 flying boat from Yokohama Kokutai (Yokohama Air Corps). It was intercepted by the pair of Thach and Sellstrom. Shortly after their return, another flying boat was shot down by the pair of Stanley and Haynes. But these two actions were only the introduction to a much larger engagement. At 14:20, a group of 17 G4M “Betty” bombers from Dai-4 Kokutai (4 Air Corps) departed the base on Vunakanau Airfield. Their target was the USS Lexington. Two flights from VF-3 – the second and the third, as well as four pilots from the first flight, Thach among them – were scrambled to defend the ship. The engagement ended in a massacre of the Japanese grouping, which lost 15 aircraft. John Thach reported shooting down one “Betty” individually and a second jointly. In total, he destroyed 2 and ½ enemy aeroplanes.

On 10 March, the USS Lexington and USS Yorktown launched an attack on Japanese landing forces in the area of Lae-Salamaua in New Guinea. Thach led his pilots against ground targets, which were strafed and pounded with fragmentation bombs. Once the mission was completed, the USS Lexington returned to Pearl Harbor, where its aviation group was transferred ashore.

The next encounter in which Thach took part was the Battle of Midway; this happened to be the last clash in which he served as a squadron commander. After the battle, Thach was assigned to train pilots in air combat tactics, and thereafter to perform staff duties as operations officer to Admiral John McCain, who at the time served as commander of the Fast Carrier Task Force. He also developed a tactic known as the “Big Blue Blanket”, which was an aerial defence against kamikaze attacks. When the war in the Pacific drew to a close, Thach was present at Japan’s formal surrender to the Allies.

After the conflict he continued his career with the US Navy, among others commanding the aircraft carriers USS Sicily and USS Franklin D. Roosevelt. In the years 1963–65, he served as Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Air in the Pentagon, while in 1965 he was appointed Commander in Chief, United States Naval Forces Europe. He retired in 1967 with the rank of Admiral.

John Thach died on 15 April 1981 in Coronado, just before his 76th birthday.

VF-3 in the Battle of Midway

From the beginning of the war, the Japanese strove to achieve an overwhelming victory and thereby force the United States to sue for peace on the Empire’s terms. Since they had been unable to attain this goal by their attack on Pearl Harbor, they planned an operation that was intended to destroy the main offensive element of the US Navy – the aircraft carriers.

They decided to strike at Midway Atoll, which lies more or less halfway between the United States and Japan. The objective was for the Japanese Army to occupy the atoll, while the American naval relief force would be destroyed by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). It is highly probable that this would have indeed been the case, had not American intelligence been able to decode enemy communications and determine the objective of the assault. With this information in hand, they proceeded to set a trap.

Initially, the US Navy planned to send two aircraft carriers – the USS Hornet and USS Enterprise – against the enemy, however thanks to the heroic efforts of the naval shipyard workers at Pearl Harbor, who somehow managed to repair the damage sustained by the USS Yorktown in the Battle of the Coral Sea (5–7 May 1942), they suddenly had an additional ship at their disposal.

The Japanese plan, codenamed Operation MI, was commenced already on 19 May, when submarine I-123 left Kwajalein Atoll in order to reconnoitre French Frigate Shoals and refuel H8K2 reconnaissance aircraft that were to survey Pearl Harbor. Other submarines sailed out on successive days. The last to depart was the I-159, which left its moorings on 30 May.

On 27 May, Admiral Nagumo’s strike force (First Air Fleet), which comprised four aircraft carriers: the Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu and Soryu, left the base in Kure. Nagumo’s primary task was to carry out the attack on Midway and neutralise all defending forces prior to the invasion. This was to be accompanied by the destruction of any US Navy ships that may have appeared in the vicinity of the atoll.

The American fleet left its base on Oahu in two waves, or task forces (TF). TF-16, commanded by Admiral Spruance and made up of two aircraft carriers, the USS Enterprise and USS Hornet, departed on 28 May, while the second grouping – Admiral Fletcher’s TF-17, a key element of which was the hastily repaired aircraft carrier USS Yorktown – followed suit only two days later, on 30 May.

The Americans enjoyed a tactical advantage even before the battle had started, for they knew of Japanese intentions from intelligence intercepts and were able to properly plan their actions, even sending long-range Consolidated Catalina flying boats to search for the enemy some 700 miles from base – a development which took the Japanese command by surprise.

Battle is joined

On 3 June 1942, American headquarters started to receive reports from the Catalinas that notified of the discovery of successive groups of enemy ships. In the afternoon, Boeing B-17 bombers from Midway dropped the first bombs on Nagumo’s ships, thus commencing the battle.

The Japanese strike force entered the fray just after 04:00 on 4 June 1942, launching 108 aeroplanes to attack the atoll. At the same time, both adversaries were feverishly on the lookout for their respective carrier groups. The Japanese ships were the first to be detected – at 05:34, by one of the Catalinas – while just under half an hour later, at 06:03, Fletcher was notified of the enemy’s position (although the report only mentioned two aircraft carriers). He immediately ordered TF-16 to move into contact with the Japanese. Leaving the USS Yorktown, his flagship, in reserve, he awaited further information about the enemy.

The USS Hornet and USS Enterprise started launching aircraft at 07:02. The operation took the Americans more than an hour to complete, and so the aeroplanes left in separate groups. It proved to be a bad day for the aerial element of USS Hornet – the torpedo bomber squadron lost all of its Devastators and 29 aviators. Only one, Ensign Gay, survived. Worse still, its fighters and dive bombers made a “flight to nowhere” – they failed to locate the enemy and, while some returned to the ship, others flew to Midway; a few had no choice but to splash down after exhausting their fuel. The group from USS Enterprise fared somewhat better. The bomber and reconnaissance squadrons found their targets and sank two aircraft carriers, the Kaga and the Akagi, although they nearly shared the fate of their colleagues from the USS Hornet. The torpedo squadron, however, was almost totally obliterated.

Thach’s dilemmas

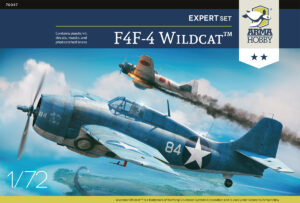

When he set off for Midway, Lt Cdr John Thach was not commanding the same unit with which he had gone off to war. Just before the Battle of the Coral Sea, he had “loaned” the majority of his pilots to VF-5, which embarked on the USS Lexington and headed for the South Pacific. Other aviators were sent back to the United States. The situation was actually quite bizarre, for at the time he was the unit’s sole properly assigned pilot. When the Battle of Midway drew near, his squadron comprised 11 flyers, some of whom were new arrivals straight from school. The American command wanted the USS Yorktown to set off for war with a complete aerial detachment, and it was therefore decided to amalgamate VF-3 with VF-42. The squadron also received new aircraft – F4F-4 Wildcat fighters, which had folding wings. This made it possible to increase the number of aeroplanes embarked on individual aircraft carriers.

The USS Yorktown launched its aeroplanes only at 08:38 – 12 TBD Devastators, 17 SBD Dauntlesses, and 6 F4F-4 Wildcats led by J. Thach. He himself recalled that before going into battle the squadron commanders held a discussion during which it was agreed that the fighters would provide cover for the torpedo bombers. The commander of VF-3 wanted 8 Wildcats, organised in two sections of four aeroplanes each, to take part in the mission. At the last moment, however, he was informed that only six fighters would be sent. Thach protested, stressing that multiples of four would be required in order to effectively employ his tactic. Unfortunately, the order was not changed.

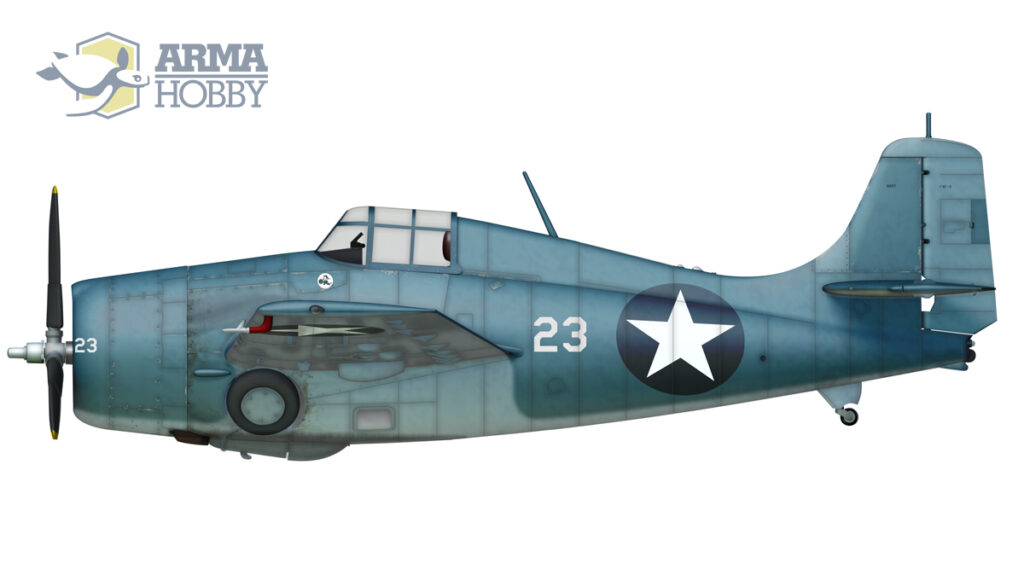

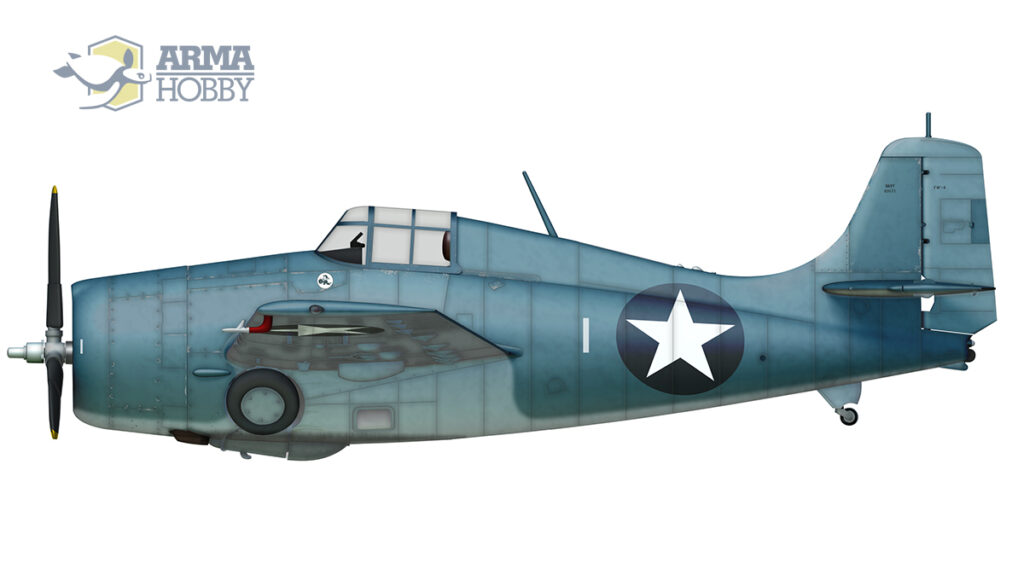

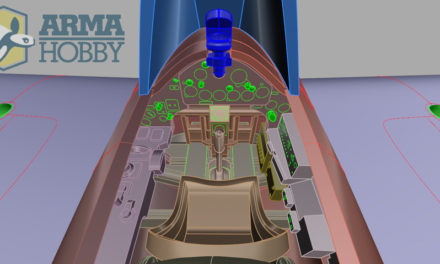

A film shot (link) of the F4F-4 Wildcat #5093/F-23 flown by Lt.Cmdr. John Thach in an escort mission of the TBD-1 Devastators from VT-3, in the Morning 4 June 1942.

Providing cover for the Devastators

Fighter cover was to be provided by the following pilots: Lt Cdr J. Thach (#5093/F-23), Ens. Robert Dibb (#5049/F-20), Lieut. (j.g.) Brainard Macomber (#5165/F-6), Ens. Edgar Bassett (#5150/F-9), Mach. Tom Cheek (#5143/F-16) and Ens. Daniel Sheedy (#5239/F-24). Thach also had one other worry – before departing for battle, he had not had the opportunity of explaining his “weave” tactic to the pilots of VF-42. This was to have been done by his deputy, Lt Cdr Donald Lovelace, however he perished on 30 May in an accident aboard the USS Yorktown while it was en route for Midway; his wingman’s Wildcat failed to catch the arresting wire and hit his aircraft, with the propeller embedding itself in the cockpit, severing Lovelace’s artery and causing extensive skull damage.

Further, the change in the number of fighters forced Thach to alter the battle formation. He, Ens. Dibb, Lieut. (j.g.) Macomber and Ens. Basset would comprise the upper cover group, flying at a height of 5,500 feet, while Mach. Cheek and Ens. Sheedy would be flying below them, at an altitude of 2,500 feet, immediately behind the Devastators.

Unlike the aviation detachments of TF-16, the aircraft of TF-17 knew the exact position of the enemy and, having arrived over the target area, wasted no time in launching their attack. The Japanese pilots, who had hitherto defended their ships against American torpedo bombers, turned to repulse the Devastators of VT-3. This time, however, they faced a rude awakening, for they were immediately confronted by the Wildcats. The element of surprise was nonetheless offset by the fact that the Japanese combat air patrol (CAP) was made up of approximately 40 Mitsubishi A6M2b “Zeroes”.

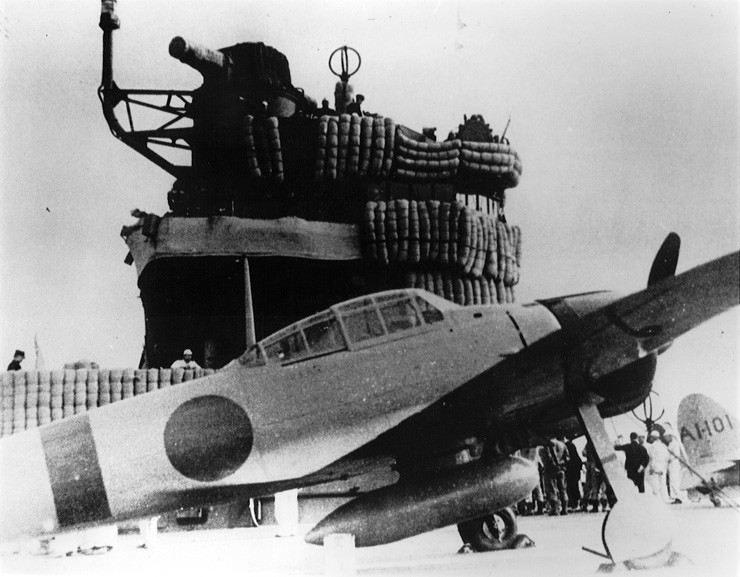

A6M2 Zero from IJN Akagi aeroplane carrier, December 1941.

The “Zeroes” enter the fray

Thach, leading the formation, saw nearly 20 fighters approaching from the direction of the enemy ships, but the brunt of the attack was borne by the pair of Macomber and Basset, who were flying somewhat to the rear. Basset was shot down, while Macomber, although having his radio damaged, soon joined up with the leading pair. Initially, Thach made repeated sharp turns towards the approaching enemy. Each time that a Japanese fighter commenced its attack, Thach would perform a sudden turn, thereby making it impossible for the enemy to fire an accurate burst. At some point one of the Japanese pilots slowed down following an unsuccessful attack; this was duly noted by the American, who immediately turned towards the “Zero” and opened fire, shooting him down. Finally, however, Thach decided it was time to put his tactic into practice. He ordered Macomber to leave the group and start “weaving”. Macomber, however, did not hear the order and continued to fly in formation. Finally, Thach instructed his wingman to turn right and start acting as if he were the leader of the pair. Doing as he was told, he took up a position parallel to Thach and Macomber. The Japanese pilots thought that the Americans had lost their nerve, and one of them moved in to attack Dibb’s aeroplane. He, however, immediately turned towards Thach, who then turned towards Dibb. Thach flew under his wingman’s aircraft and fired at the Mitsubishi “Zero”, which burst into flames and fell to the ocean. Ens. Dibb, although being one of the new arrivals to VF-3, quickly understood the tactic and reacted instantly to the threat. During one of the attacks against Dibb’s aircraft, the Japanese pilot did not turn to keep behind his opponent, instead continuing to fly straight. Thach, surprised, quickly exploited his error and fired off a burst, sending the “Zero” oceanwards. This was his third kill of the day. Ens. Dibb also scored a victory, shooting down an aeroplane that was attempting to attack the pair of Thach and Macomber. The latter got into a shooting position only once, and after landing reported a probable kill.

Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat #5093/F-23 flown by Lt. Cmdr. John Thach in an escort mission during attack on Japanese carrier force in the morning of 4 June 1942. Artwork by: Zbyszek Malicki.

The Wildcats hold their own

During this time, the third pair from Thach’s flight was engaged in fierce combat with other Imperial Japanese Navy fighters which had been attacking VT-3’s Devastators. Some of the Japanese pilots would repeatedly launch themselves against the leading torpedo bombers, and then turn back to renew their onslaught. But they failed to notice the cover fighters. One soon paid the highest price – Cheek opened fire, hitting his engine and the underside of the fuselage. Engulfed in flames, the “Zero” hurtled into the Pacific. Cheek then turned his attention to two other aeroplanes that were attempting to attack VT-3; surprised, the enemy flyers were forced to cease their attack. A moment later, however, the American pilot himself ran into trouble when a Japanese aeroplane got onto his tail. Luckily, his wingman, Ens. Sheedy, was in position and drove the enemy off. Cheek immediately headed for the clouds, hoping that he would regain contact with the rest of VT-3. Instead, he stumbled upon a group of A6M2s. He instantly fired at one of them, shooting it down, and then opened up on another. But he was unable to see whether his shooting had been effective, for he prudently flew back into the clouds.

His wingman was coping just as admirably with the superior numbers of enemy fighters. Initially, he maintained his position behind his leader, protecting him from the Japanese aeroplanes. At one point he was attacked; bullets damaged his Wildcat, while he himself was hit in the ankle and arm. Worse still, the shells severed one of the landing gear chains, causing one of the wheels to partially slip out. Wasting no time, Sheedy headed for the clouds. But after he left them he saw that his Wildcat was being chased by 4 enemy aircraft. Without hesitating, he dived in order to gain speed and break away from his opponents. While performing this manoeuvre, he saw a single “Zero” which, as it seemed, was trying to cut off his escape route. Flying head on to each other, the pilots opened fire. A moment later, they ducked to avoid a collision, and the Japanese flyer caught the surface of the water with his wing tip, perishing in seconds. Following the fight, Sheedy turned back to his aircraft carrier.

The pilots of Fighting Squadron Three had performed an incredible feat, shooting down 6 enemy fighters (Thach 3, Dibb 1, Sheedy 1 and Cheek 1) and damaging two (Macomber and Cheek). All for the price of a single Wildcat. And although the aviators of VF-3 had failed to defend VT-3 (Torpedo and Bombing Squadron 3), both squadrons had achieved something more important still. Namely, they had occupied the Japanese CAP fighters in a low-level dogfight, thus allowing the Dauntless dive-bombers from VB-6, VS-6 and VB-3 to attack the enemy aircraft carriers at their leisure; ultimately, the Dauntlesses accounted for three of the Japanese ships – the Akagi, Kaga and Soryu. The last carrier from Nagumo’s strike force, the Hiryu, would also share their fate, however not before launching two successful attacks on TF-17.

Crash landing of F4F-4 Wildcat (#5143/F-16) piloted by Mach. Tom Cheek after returning from attack on Japanes carrier force. See youtube footage with pilot’s narration link. Noteworty are good shots of aeroplane weathering from all sides visible during its collapse.

Fighting Squadron Three in defence of the USS Yorktown

The attempted defence of VT-3 was not the last action in which VF-3 took part that day. The next engagement turned out to be equally important – protecting the squadron’s own aircraft carrier against attack by Japanese bombers and torpedo bombers.

The American dive-bombers had disabled three enemy aircraft carriers. But one – the Hiryu – still remained, and its commander, Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, was an able and aggressive officer. Just before 11:00, Yamaguchi sent 24 aeroplanes – 18 D3A “Val” bombers with a cover element of 6 A6M2 “Zeroes” – to attack the American fleet. That the Japanese crews were experienced and excellently organised is attested to by the fact that the entire group of 24 aircraft needed just 4 minutes to take off.

While on their way to the target, the IJN pilots noticed a returning group of American bombers, and the cover element launched an attack. This turned out to be a costly mistake, and the Japanese lost two fighters.

The first attack against the USS Yorktown

Meanwhile, American radar operators had discovered an enemy strike force some 40 miles from their own ships, and 20 fighters – 12 from the USS Yorktown, 4 from the USS Enterprise and 4 from the USS Hornet – were immediately scrambled to deal with the threat. They managed to intercept the Japanese and shoot down 13 bombers and 3 fighters. Nevertheless, the USS Yorktown received 3 hits, one of which damaged its boilers. Upon their return, the Japanese pilots reported that they had disabled one enemy ship.

The commander of 4th Flight, Lieut. Brassfield, was first to notice the approaching “Vals”, which were flying at a higher altitude than his Wildcats. He decided to climb above the enemy and attack from an advantage of height. However, two pilots from his flight, Lieut. (j.g.) William Woolen and Ens. William Barnes, attacked the enemy from beneath, causing the Japanese formation to break up. Lieut. (j.g.) Elbert McCuskey, flying behind Woolen and Barnes, scored his first victory when he found himself between two groups of Japanese dive-bombers. Turning left, he fired at one of the aeroplanes at nearly point-blank range, and the enemy aircraft burst into flames. He then proceeded to shoot down two other aeroplanes and damage 3 more.

Other pilots of Fighting Squadron Three also had success. Brassfield damaged one D3A1 in a frontal attack. The Japanese pilot had attacked his Grumman with a 250 kg bomb attached to his fuselage; this did not improve his chances, for while his aircraft lacked manoeuvrability, its armament – two 7.7 mm machine guns – was clearly inferior to the F4F’s six half-inch Brownings. Soon, Brassfield spotted three bombers flying towards the USS Yorktown, and he shot down all three in just under a minute. When climbing after having shot down the last of the trio, he noticed another Japanese aeroplane, which he attacked head-on and downed, too. Another pilot who gained multiple victories in the engagement was Dibb, who destroyed two “Vals”. The first burst into flames when a burst from Dibb’s Brownings hit its fuel tank. He scored his second kill after he reached the height at which the dogfight was taking place.

Overall, during the initial encounter the pilots of Fighting Squadron Three reported downing 13 bombers and damaging 8, and also destroying 3 fighters. Due to the damage suffered by the USS Yorktown, its fighters landed on the USS Hornet and USS Enterprise.

Nakajima B5N “Kate” torpedo bomber, from Japanese war movie “Hawai Mare oki kaisen” (“Sea War from Hawai to Malaya” 1942). Photo – Wikimedia Commons.

The USS Yorktown comes under renewed attack

The second wave of Japanese aircraft, comprising 10 B5N2 “Kate” torpedo bombers and 6 A6M2 “Zeroes”, took off at 13:30. Radars discovered the formation 25 minutes later, and fighters were immediately scrambled. The American defensive element was a mixed group, made up of pilots from VF-3 and VF-6 commanded by McCuskey (6 Wildcats in all), eight fighters launched from USS Yorktown and commanded by Thach, and eight aircraft that had originally formed part of the CAP flying over TF-16.

McCuskey was the first to close in on the enemy, however he himself and three pilots from his detachment flew right past the Japanese bombers. This was due to the fact that Cdr Tomonaga, who commanded the Japanese formation, had already started to lose altitude in order to gain speed before the attack, and therefore avoided McCuskey’s flight. Seconds later, however, the Japanese ran into the pair of pilots from VF-3 (Woolen and Dibb) who had been assigned to McCuskey’s flight – both had set off for TF-17 a touch later than their colleagues. Seeing the Japanese aircraft at 4,000 feet, they attacked without hesitation. Attacking from 7,000 feet, Woolen targeted the last aeroplane of 1st Chutai (squadron), which burst into flames and fell into the ocean. His joy at his victory was short-lived, however, for a second later he himself was attacked and hit, being forced to splash down near the American ships. Dibb was not as lucky, for he was set upon by the cover fighters even before he had a chance of attacking the formation of “Kates”.

On the USS Yorktown, meanwhile, Lt Cdr Thach waited impatiently in the cockpit of his F-1/3171(5174) to take off. The order was finally given at 14:40. Thach was the first to attack the enemy. Shortly after take-off, he saw one of the “Kates” getting ready to launch its torpedo. Wasting no time, he fired off a burst from a slight advantage of height; the enemy pilot managed to drop his torpedo, but the aircraft then hit the surface of the ocean and disintegrated. As it turned out, his victim was the commander of the Japanese assault – Captain Joichi Tomonaga.

Captain Joichi Tomonaga

Joichi Tomonaga was born in 1911 in Beppu. He graduated from the Imperial Japanese Naval College in 1931. After completing a piloting course in 1934, he was assigned to the Omura Kokutai (Omura Air Corps). In November of the same year, he was promoted to lieutenant and posted to the aircraft carrier Akagi. He served on the ship until 1937, when he was transferred to the carrier Kaga. During the Battle of Midway, he commanded the flying unit (Hikotai) of the aircraft carrier Hiryu. In the course of combat over the atoll, his B5N2 was damaged when bullets hit one of the fuel tanks. In spite of this, he led the second attack against the USS Yorktown, during which he was shot down by Lt Cdr John Thach.

Joichi Tomonaga was born in 1911 in Beppu. He graduated from the Imperial Japanese Naval College in 1931. After completing a piloting course in 1934, he was assigned to the Omura Kokutai (Omura Air Corps). In November of the same year, he was promoted to lieutenant and posted to the aircraft carrier Akagi. He served on the ship until 1937, when he was transferred to the carrier Kaga. During the Battle of Midway, he commanded the flying unit (Hikotai) of the aircraft carrier Hiryu. In the course of combat over the atoll, his B5N2 was damaged when bullets hit one of the fuel tanks. In spite of this, he led the second attack against the USS Yorktown, during which he was shot down by Lt Cdr John Thach.

Photo:

The next “Kate” was shot down by Lieut. (j.g.) William Leonard, who attacked it immediately after taking off. The enemy pilot succeeded in launching his torpedo, but a moment later his flaming aircraft fell into the water. Another aviator from VF-3, Ens. John Adams, had even less time after take-off, however he managed to get on the tail of an enemy aeroplane and shoot it down.

Tomonaga was shot down by

The second wave of torpedo bombers

In the meantime, the second group of Japanese torpedo bombers arrived over the battlefield and dropped their missiles in the direction of the American aircraft carrier. Two of them hit the side of USS Yorktown. The fifth pilot of VF-3 who managed to take off, Mach. “Tom” Barnes, quickly directed himself towards the enemy, however before acquiring a B5N2 he was himself attacked by two “Zeroes”; luckily, he avoided being shot down. These two Japanese pilots, however, then became the victims of McCuskey and Mel Roach from VF-6. McCuskey made use of the speed which he gained when diving, and shot down his opponent while climbing in a loop.

During this time, other pilots of VF-3 scrambled from the deck of USS Yorktown. In all probability, Ens. Tootle fell victim to friendly fire, while Ens. Harper, who upon taking off flew along the American ships to gain speed, was quickly targeted by two Japanese fighters and perished in the debris of his Wildcat.

F4F-4 Wildcat pilotowany przez Ens. H. A. Bass, USNR z VC-3 ląduje na pokładzie USS Hornet ok 15:30 4 czerwca 1942. Zdjęcie US Navy.

After the battle, all of the Grummans that had been flying over TF-17 were redirected to the USS Hornet and USS Enterprise. VF-3 reported shooting down eight B5N2 “Kate” torpedo bombers and two A6M2 “Zeroes” in the dogfight, losing 4 Wildcats and one pilot. Shortly after, the aircraft carriers of TF-16 launched their Dauntless dive-bombers, which sank the last Japanese carrier – the Hiryu. Although the battle was still raging, the sinking of the last aircraft carrier from Admiral Nagumo’s First Air Fleet sealed American victory.

English translation by Maciek Zakrzewski

See also:

- F4F-4 Wildcat kitno. 70047 with Lt. Cdr. Thach markings and other in the Arma Hobby webstore.

Dywizjon „Świętych” – najskuteczniejsza jednostka Wildcatów US Navy

An enthusiast of air war during the Battle of Britain, over North Africa and Italy, over South East Asia and France in 1940. In free time builds models in 1/72 scale, and from time to time in 1/48 scale.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski

Good story guys, very interesting! Also curious to see your new 1/72 F4F-4 Wildcat model after the Airfix plane. There is always chance to do something better. Let us hope to see also a new F4F-3 coming in the line 🙂 Or what about an F4F-7?

Thank you for your kind words. I am pleased that you like the article.

F4F-3 is in our plans for future. Hard to tell about F4F-7.