Roughly speaking, wartime fighter pilots can be classified into one of four groups.

- Among the first were those who gained aerial victories and survived every dogfight. These were all excellent fliers and marksmen, however, in order to become seasoned fighter pilots, they first had to make it through their initial period of service, during which the risk of being shot down far exceeded the probability of destroying any enemy aircraft.

- The second group comprised those who achieved kills, but perished. The difference between them and the fliers from the first group consisted, as I see it, in a lack of luck, and perhaps in a greater willingness to undertake risk. Many superb pilots also died in the crashes of their aeroplanes, or were claimed by anti-aircraft artillery.

- The third was made up of aviators who had no aerial victories but nevertheless managed to survive the war. These were pilots who either lacked aggression and marksmanship skills or served at times and locations where chances of meeting the enemy were minimal.

- Finally, we come to the fourth group – the unlucky fellows who died without achieving even a single victory. Sometimes, their deaths came so early that we do not know whether they could have made the grade and actually developed into successful fighter pilots.

Stanley Michel “Mike” Kolendorski perished during his first contact with the enemy, and therefore had no way of demonstrating any latent potential. While he did not, perforce, belong to the third group, many of his colleagues opined that his extreme nature predisposed him to become the first “Eagle” to receive the DFC, or the first to fall in combat.

“Mike” was born on 24 February 1915 in Jersey City into a family with Polish roots. The influence of his familial environment, and in particular that of his grandfather, who had emigrated from Poland to the United States following the failed January Insurrection of 1863–1864, was such that Kolendorski spoke fluent Polish and espoused patriotic sentiments. His reaction to Poland’s defeat in 1939 was an obvious consequence of having been raised among people who had never forgotten their homeland. When he took the decision to enlist in the RAF, he had already been married for more than a year, lived in California, and had undergone basic training in light civilian aircraft. Although his wife made it clear that she would file for divorce if he joined the RAF, he rejected her ultimatum out of hand. Kolendorski’s mix of emotional patriotism and an explosive personality precluded any other outcome. And so his spouse, Charlotte, was left abandoned, while “Mike”, passing through Canada, arrived in Liverpool on 10 August 1940.

The beginnings of the first Eagle Squadron

The formation of No. 71 Squadron was a process that occurred analogously to the creation of the La Fayette Escadrille (N 124) in France in 1916, and of the 7th Tadeusz Kościuszko Squadron in Poland three years later.

Hurricane Mk I from 71 Squadron, early 1941. Photo: WikimediaCommons.

When Europe was once again engulfed in flames in 1939, there was no shortage of American volunteers ready to follow in the footsteps of their famous predecessors from the Great War, whose popularity had been consolidated in evocative writings, comic books, and Hollywood films. This was accompanied by the emergence of people who organized and sponsored enlistment. First among them in England were Colonel Charles Michael Sweeny and his nephew, Charles Francis Sweeny. The elder Charles already possessed considerable experience, crediting himself with being involved in the recruitment of American citizens for the Polish-Bolshevik War, and even claiming that he was a Polish general, although the latter finds no confirmation in Polish topical literature. Whatever the case may have been, he was an immensely colourful person, having fought in seven wars as the soldier of five different armies. He was also a friend of Ernest Hemingway, who doubtless had his share in further embellishing the Colonel’s life story. The younger Sweeny, who lived in London, was a prosperous businessman and had excellent social contacts among politicians and the upper classes.

The thirty-two pilots raised by the Sweenys arrived in France too late to receive training, let alone engage in operational flying. When the Germans attacked on 10 May 1940, it soon became clear that this was a different war to that fought by Lufbery and Rickenbacker. The Blitzkrieg forced these prospective fighter aces to flee to the British Isles. Not all of them succeeded – four perished, and six were taken prisoner. Of those who survived, only five would later take part in the Battle of Britain, flying with British squadrons. The American pilots, whose government at the time adhered to a foreign policy of isolationism, focused the attention of the media and rapidly became a pawn in propaganda efforts aimed at drawing the United States into the war. An idea was soon proposed to create a wholly American fighter unit within the RAF, and, in spite of initial British scepticism, it was followed through. The decision must certainly have been influenced by the fact that the RAF was being bled white by the German aerial offensive and desperately needed all the support it could receive. Additionally, Polish and Czech squadrons had already been created, so the precedent was there.

The thirty-two pilots raised by the Sweenys arrived in France too late to receive training, let alone engage in operational flying. When the Germans attacked on 10 May 1940, it soon became clear that this was a different war to that fought by Lufbery and Rickenbacker. The Blitzkrieg forced these prospective fighter aces to flee to the British Isles. Not all of them succeeded – four perished, and six were taken prisoner. Of those who survived, only five would later take part in the Battle of Britain, flying with British squadrons. The American pilots, whose government at the time adhered to a foreign policy of isolationism, focused the attention of the media and rapidly became a pawn in propaganda efforts aimed at drawing the United States into the war. An idea was soon proposed to create a wholly American fighter unit within the RAF, and, in spite of initial British scepticism, it was followed through. The decision must certainly have been influenced by the fact that the RAF was being bled white by the German aerial offensive and desperately needed all the support it could receive. Additionally, Polish and Czech squadrons had already been created, so the precedent was there.

Photo: Official 71 Squadron RAF badge, 1940. WikimediaCommons.

The first entry in the new squadron’s ORB (Operations Record Book) was made on 19 September 1940. It was on that day that three pilots from No. 609 Squadron – P/O Andy Mamedoff, P/O “Shorty” Keough and P/O “Red” Tobin, veterans of the fighting in France – arrived at the unit’s base in Church Fenton. These men had also gained some combat experience in England, achieving a number of kills while flying Spitfires. P/O Tobin had downed two German aeroplanes, while Mamedoff and Keough had one half of a kill each.

Over the next few weeks, they were joined by other aviators, however the squadron did not actually have any aircraft of its own until 24 October. This discouraged one of the new arrivals, P/O Donahue, who asked, successfully, to be reposted to his original unit, No. 64 Squadron.

But when the Americans finally received their first aeroplanes, there was not much cause for joy. The aircraft, Brewster Buffaloes, were not suited for combat against the Luftwaffe, and I highly doubt whether RAF command actually planned to engage No. 71 Squadron thus equipped in the fighting over France. Three of the aeroplanes were used for training only, and the ongoing Battle of Britain generated such losses in equipment that it was simply impossible to provide the unit with any Hawker Hurricanes. Whereas the imputation, which has been repeated in numerous publications, that the pilots were purportedly so disappointed to have received second-rate aircraft that they intentionally damaged all the Brewsters, finds no confirmation in their operational histories. Indeed, there were two incidents, however neither looks like sabotage. In the first, the pilot suffered a slight head injury when he overshot the landing strip and the aeroplane nosed over, while during the second, which occurred already after the decision had been taken to re-equip the unit with Hawker Hurricanes, an inspection panel in the rear of the fuselage opened, disturbing the airflow and substantially hindering both control and landing, although the aircraft involved was not damaged.

Three American pilots of No. 71 (Eagle) Squadron RAF, Pilot Officers G Tobin, V C ‘Shorty’ Keough, and A Mamedoff show off their new squadron badge at Church Fenton, Yorkshire, October 1940. Photo: WikimediaCommons.

During this time, No. 306 (Polish) Squadron was also stationed at Church Fenton. On 1 November, expecting to be transferred after having obtained operational status, the Polish pilots organised a grand farewell party. But the foul weather prevented their planned move to Turn Hill, thus giving the opportunity of holding yet another celebration on the evening of 3 November. It had to have been a very solemn gathering indeed, for the chronicler of No. 17 Squadron noted that the Poles had promised to definitively leave the airfield the next day, as if he were afraid that his own pilots might not have endured a third, equally festive farewell. The Polish squadron ultimately departed for Turn Hill only on 7 November, however there is no mention of any further partying.

Doubtless the squadron’s young pilots, being forced to remain planeless for so long, whiled away the days as intensely as they could, and spending time with their Polish comrades-in-arms must have been an appealing prospect. A photograph of the first three “Eagles” (Mamedoff, Keough and Tobin) standing next to a Hurricane marked with a white and red checker-board has survived to our times. They were posing in front of a Polish aircraft because they still had none of their own.

Mike Kolendorski among the “Eagles”

On 7 November, the Americans finally received their first Hawker Hurricanes, which were handed over by No. 85 Squadron. On the same day, a group of new pilots arrived from No. 5 Flying Training School RAF, among them “Mike” Kolendorski. The unit’s chronicler found it appropriate to observe that the new pilot spoke Polish. It is somewhat of a pity that he did not note down other character traits of the aviators, for they were without doubt a mixed bunch of unusual men, many of whom were of less than spotless integrity. One of the newcomers of 7 November was Byron Kennerly, who spent barely three months with the unit before being sent back to America due to his “unsuitability”. This was a broad reference to his habitual flouting of discipline and drunkenness, which successive warnings did nothing to temper. He nevertheless made a career for himself in the United States, and soon published a book entitled “The Eagles Roar!”. In it, he depicted dogfights in which he had never taken part, perhaps only hearing about them in the mess. Kennerly went on to become a Hollywood consultant, and was engaged in the filming of “International Squadron”, in which Ronald Reagan played the lead role. In later years, he was jailed following a bank robbery.

Pilots of the 71 “Eagle Squadron” RAF posing at the Hurricane , 17 March 1941. Third from left stands Mike Kolendorski. Photo: WikimediaCommons.

Kennerly was the most extreme example, however the behaviour of the other fliers, Kolendorski among them, was equally problematic; in fact, the RAF grew so tired of their lack of discipline that at one stage it was even planned to end the experiment and send all the hot-tempered Yankees back home. But the image losses would have been irreparable, potentially wrecking the propaganda effort put into drawing the United States into the war.

Nevertheless, training proceeded with difficulty. The underlying cause was the very organisation of recruitment, which was conducted without any thorough vetting. Thus, the Eagles were joined by both immature individualists incapable of observing discipline, or indeed by psychopaths such as Kennerly, and also men who were simply unqualified to fly or even had medical problems that should have disqualified them as pilots. Further, they would regularly overstate numbers of hours flown and falsify documents submitted to the draft board. This resulted in numerous accidents, which, in turn, prevented the squadron from achieving operational readiness for months. Before the unit actually joined the fight, five pilots were lost in training flights.

The first contact with the enemy was hugely disappointing. On 17 April 1941, P/O Daymond attempted to intercept a Dornier Do 17, however he was unable to catch up with the bomber. At the time, he was flying the Hurricane that was normally used by Kolendorski, who never bothered himself with observing operating limitations and regularly overused his booster, completely ignoring the fact that this necessitated time-consuming engine overhauls. The mechanics finally decided to disconnect the booster, and Daymond was unlucky enough to run into the German bomber with the fighter in this condition, inadvertently saving the German crew from harm.

The “Eagles’” skills (or lack thereof) in the early days of the squadron can be illustrated by a dogfight which took place on 15 May 1941, when two Hawker Hurricanes were attacked by a lone Messerschmitt while patrolling over a convoy. The German, focusing on the aeroplane flown by P/O Flynn, disregarded the second Hurricane. Its pilot, P/O Alexander, managed to get onto the Messerschmitt’s tail and open fire. Although he expended his entire ammunition, the result was an embarrassment. The Messerschmitt escaped but Flynn, who had been in front of the enemy fighter, suffered the full brunt of Alexander’s indiscriminate shooting and had to make a forced landing.

Pilots of the 71 Squadron scramble, 17 March 1941 r. Photo: WikimediaCommons.

At the time, the squadron was commanded by S/L Bill Taylor, who made every effort to discipline his subordinates and turn them into effective combat pilots. One of his first decisions after taking over the unit was to send Kennerly back home. Kolendorski, too, should probably have been repatriated to the United States, for he was equally unadapted to military life, however in his defence was the fact that he was a better flier than most of his colleagues. In the beginning of May 1941, Kolendorski, in all likelihood bored by the tasks which his commander, having due regard for the current state of training of his unit, thought it necessary to perform, started “guest flying” with No. 3 Squadron, perhaps hoping to improve his chances of finally achieving a kill.

S/L Taylor’s approach, which was based on a realistic assessment of the abilities of his subordinates and a comprehensive awareness of just how much they had to do in order to become capable fighter pilots, caused the “Eagles” to turn against him. Ultimately, he was forced to leave his post. Before this occurred, however, a chance event confirmed that Taylor was right in considering his fliers as unprepared for combat.

Kolendorski’s first – and last – fight

In the evening of 17 May 1941, eleven of the squadron’s fighters flew out on patrol over the Thames Estuary. At a height of 20,000 feet, they came across a formation of four Messerschmitts, which, taking note of their numerical inferiority, refrained from taking undue risks. Acting with caution, two of the Germans broke from formation and passed next to the Americans on an opposite heading. This was a provocation to which experienced and disciplined fliers were immune. Kolendorski, however, did not see the trap, instead thinking that he was within arm’s reach of his first kill. Without giving any notification of his planned manoeuvre, he turned and gave chase. It was a fateful decision. The two loitering German fighters, with the sun behind their backs, dived and hit the Hurricane even before it managed to get near the bait. To the horror of his watching colleagues, who must have hoped against hope that “Mike” would manage to bail out, Kolendorski’s aircraft entered an inverted spin and fell to earth. The fighter smashed into the water, ending the American pilot’s short and tempestuous life. His body was washed up onto the Dutch coast on 13 August, and he was buried at the cemetery in Rockanje.

Kolendorski was the unit’s first combat casualty – one of many. For while the “Eagles” eventually became noted for their aerial victories (in the autumn of 1941 they were the most effective fighter squadron in England), they paid a horrendous price. By the end of 1941, five pilots had died in combat, six were taken prisoner, and twelve perished in accidents.

Kolendorski’s Hurricane was the 34th kill of Heinz Bretnütz, Gruppenkommandeur of II./JG 53 and a veteran of the Legion Condor, with which he had achieved his first kills. The difference in experience and skills between the two aviators was immense, and Kolendorski’s fate was in fact sealed when he decided to attack the German fighters. As it turned out, this was Bretnütz’s last victory on the Western Front. His Gruppe was soon transferred east, and on 22 June 1941 took part in the attack on the USSR. Bretnütz, somewhat similarly to Kolendorski, was shot down and seriously wounded in his unit’s first aerial engagement. He died a few days later.

Kolendorski’s Hurricane was the 34th kill of Heinz Bretnütz, Gruppenkommandeur of II./JG 53 and a veteran of the Legion Condor, with which he had achieved his first kills. The difference in experience and skills between the two aviators was immense, and Kolendorski’s fate was in fact sealed when he decided to attack the German fighters. As it turned out, this was Bretnütz’s last victory on the Western Front. His Gruppe was soon transferred east, and on 22 June 1941 took part in the attack on the USSR. Bretnütz, somewhat similarly to Kolendorski, was shot down and seriously wounded in his unit’s first aerial engagement. He died a few days later.

Hptm. Heinz Bretnütz, Photo: www.luftwaffe.cz

Kolendorski was commemorated by naming a street near his home after him. Kolendorski Road is actually a minor forest way that ends in a cul-de-sac, and is probably unknown to even neighbourhood residents. Its name appeared in the local media only a few years ago in connection with the shameful behaviour of neo-Nazi sympathisers, who painted a giant swastika on the asphalt; their act must be viewed as a cruel joke when set against the life choices of the road’s namesake.

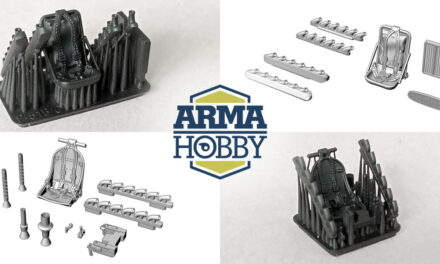

Sadly, even some of “Mike’s” relatives from the younger generation are unaware of his tragic fate. Arma Hobby’s new kit is a faithful recreation of Kolendorski’s Hurricane, and allows us to revive his memory as that of a man who, being guided by his affection for the land of his forefathers, abandoned a comfortable life in California and embarked on a mission which ultimately cost him his life.

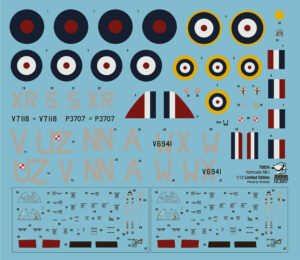

Paint scheme and markings

The paint scheme has been recreated on the basis of a film which is available on the internet. The serial number, as on certain other of the unit’s aircraft, was painted over. Further, the fighters had seen extensive service during the Battle of Britain, when they were flown by No. 85 Squadron, and thus their appearance was far from “factory new”. According to the ORB of No. 71 Squadron, Kolendorski mainly flew number P3664, which in all probability was the serial number of the Hurricane used as the model for our reconstruction.

Hurricane Mk.I XR-S, 71 Eagle Squadron RAF. Serial overpainted, probably P3664. Kirton-in-Lindsey, March 1941. Pilot F/O Stanley Michel “Mike” Kolendorski. Artwork by Zbyszek Malicki.

While photographs of Kolendorski standing in front of his aircraft, with the letter “S” visible on the front of the fuselage and the Eagle Squadron emblem on the right engine cowling, have been known for years, the film also presents the left side of the Hurricane, adorned with the typically small code letters. I was actually overjoyed to discover that the aeroplane had a small checker-board affixed beneath the cockpit rim. It was probably the same as that which the pilot carried on his “Sidcot” flying suit.

While photographs of Kolendorski standing in front of his aircraft, with the letter “S” visible on the front of the fuselage and the Eagle Squadron emblem on the right engine cowling, have been known for years, the film also presents the left side of the Hurricane, adorned with the typically small code letters. I was actually overjoyed to discover that the aeroplane had a small checker-board affixed beneath the cockpit rim. It was probably the same as that which the pilot carried on his “Sidcot” flying suit.

Eagle Squadron emblem, artwork by Zbyszek Malicki.

Another interesting element is the replacement sheet metal mounted slightly left of centre on the fighter’s underside, which was not painted black before Kolendorski’s death.

English translation by Maciej Zakrzewski.

You may be interested:

- Buy Hurricane Mk I “Allied Squadrons” and other Hurricane model kits in Arma Hobby webstore

Model maker for 45 years, now rather a theoretician, collector and conceptual modeller. Brought up on Matchbox kits and reading "303 Squadron" book. An admirer of the works of Roy Huxley and Sydney Camm.

This post is also available in:

polski

polski

Thank you for the research to find out more about my family which I had no knowledge of any of this, still searching for roots